“Grammar Nonsense and What To Do about It”: Hugh Dellar and Andrew Walkley – Book Review

Grammar nonsense is everywhere in ELT. Look a little more closely at the contents of coursebooks, grammar manuals and teacher training guides.

I realised many moons ago that publishers, syllabus writers and many teachers have gone grammar mad. However, I ordered a copy of Hugh Dellar and Andrew Walkley’s book, Grammar Nonsense and What To Do about It, to see which grammar items the authors have on their “pointless structures to teach” list.

Grammar Nonsense and What To Do about It: The book in a nutshell

Like me, Dellar and Walkley promote “what might be broadly seen as a lexical approach to teaching and learning”.

Even though the authors might favour the teaching of multi-word items, such as phrasal verbs, over the merciless dishing out of rules pertaining to the various uses of the present simple, it doesn’t mean they “only teach words” and completely reject the teaching of grammar.

Dellar and Walkley have a bone to pick with grammar fanatics who hold a highly prescriptive view of grammar. The authors convincingly show throughout Grammar Nonsense that things are not always as rigid as the grammar loonies would have us believe. For example, we learn that in American English - and increasingly in British English - there is little difference between must and have to (Swan, 2016, cited in Dellar and Walkley, 2020).

I try not to recall all the hours I wasted getting half-interested students to do must vs have to gap-fill exercises. If I attempted to reflect, I would end up in a very dark place.

The English language is predominantly lexical. The availability of huge corpora - databases of used language in real-life spoken and written English - proves that “many prescriptive rules simply don’t stand up to scrutiny”. (Dellar and Walkley, p.8).

Still, the point is that Dellar and Walkley are not grammar trashers. They rightly recognise that vocabulary and grammar are “thoroughly intertwined”. Yet, conservative coursebook editors refute common sense and logic. They prefer old rules “that have been passed down through the generations”. (Dellar and Walkley, p.9).

Finally, the chapters in the book were originally written as blog posts on the authors’ website.

Entertaining rants and meditations indeed.

Standout examples of grammar nonsense put forward by Dellar and Walkley

1. Reported speech

Chapter 1 opens ominously: “Is there anything that is more bizarrely and unnecessarily taught in ELT than reported speech?”. (p.13).

Reported speech - that old friend I haven’t encountered since the school year of 2008-09.

In this very memorable stint in my career as an EFL teacher, the boss of the language school I was working at ordered me to mercilessly drill the rules of reported speech into dozens of tortured teenagers.

What is reported speech?

Reported speech is also known as “indirect speech”.

Let’s imagine Roger said:

I’m going to the theatre next week

Much later, you might want to tell someone else what Roger had said.

So you report the original speaker’s words and thoughts in your own words, possibly using the conjunction ‘that’, and changing pronouns, tenses and other words where necessary. Hence, according to grammar reference books and grammar fanatics:

Roger said he was going to the theatre the following week

However, it all depends on context. If it’s still the same week when Roger said “I’m going to the theatre next week”, I’d personally report Roger’s utterance thus:

Roger said he’s going to the theatre next week

When is reported speech used?

We use reported speech when we are interested in the essential information a speaker has conveyed. This is in contrast to “direct speech” which conveys exactly what someone has said.

Why do Dellar and Walkley have an issue with reported speech and the way it’s taught?

Let’s take a look at why Dellar and Walkley are so het up about reported speech:

(a) Examples of “reported speech” should be seen as examples of plain old narrative tenses

The main thing about reported speech that rubs the authors up the wrong way is that (p.14):

the use of tenses, pronouns, time phrases and all the other guff isn’t actually different to the way tenses, pronouns, and time phrases are used at any other time.

When it comes to normal indirect speech, we tend to report the generality of what's been said. It doesn’t really boil down to transforming things that we've heard according to the obscure rules of tense backshifting (more on that soon!). Instead, we tell a kind of story.

When we tell this story - be it ‘the story’ of an entire conversation or just a snippet of what was said among other actions - we use tenses, pronouns and time phrases in the same manner as we would when we tell any other kind of story that occurred in the past.

The authors offer the following examples of narrative tenses:

She said she was feeling unwell so she sat down and we got her a glass of water

He told me he hadn’t spoken to anyone about it before

They said they would call back later

Unfortunately, the authors’ refusal to get drawn into labelling such utterances as stonewall cases of reported speech has got them into trouble with editors before.

He told me hadn’t spoken to anyone about it before. Personally, I’d teach this as part of a class on the “past perfect”. Why do we have to put students through all this reported speech misery?

People where I’m from (Wellingborough, UK) would probably just say “ain’t” instead of hadn’t or hasn’t.

Should we hunt down the good Wellingburians themselves and have them shot at dawn for not using a past perfect form?

No.

Let’s embrace such dialectal variation before English dialects disappear altogether.

(b) Rules pertaining to the backshift of tenses are largely redundant

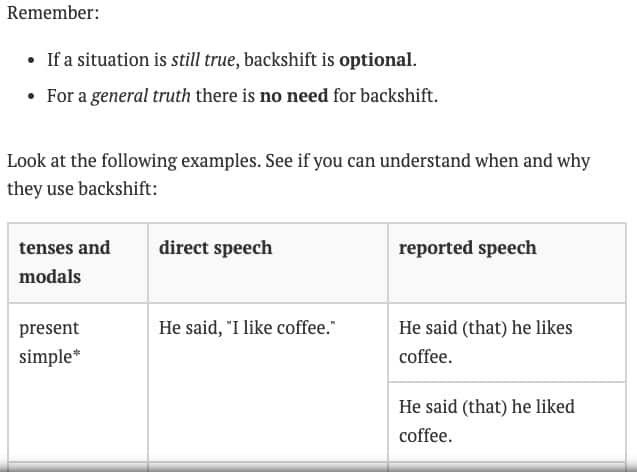

Dellar and Walkley touch on the process known as backshift.

Backshift refers to the conversion of a present tense in direct speech to a past tense in reported speech (or a past tense to past perfect).

There’s too much misleading information out there regarding backshift.

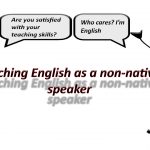

Take what the lovely Seonaid, the owner of perfect-english-grammar.com, produced in relation to reported speech.

(Warning - complete grammar nonsense!)

Occasionally, we don't need to change the present tense into the past if the information in direct speech is still true (but this is only for things which are general facts, and even then usually we like to change the tense).

To illustrate such nonsense, take a look at Seonaid's example below:

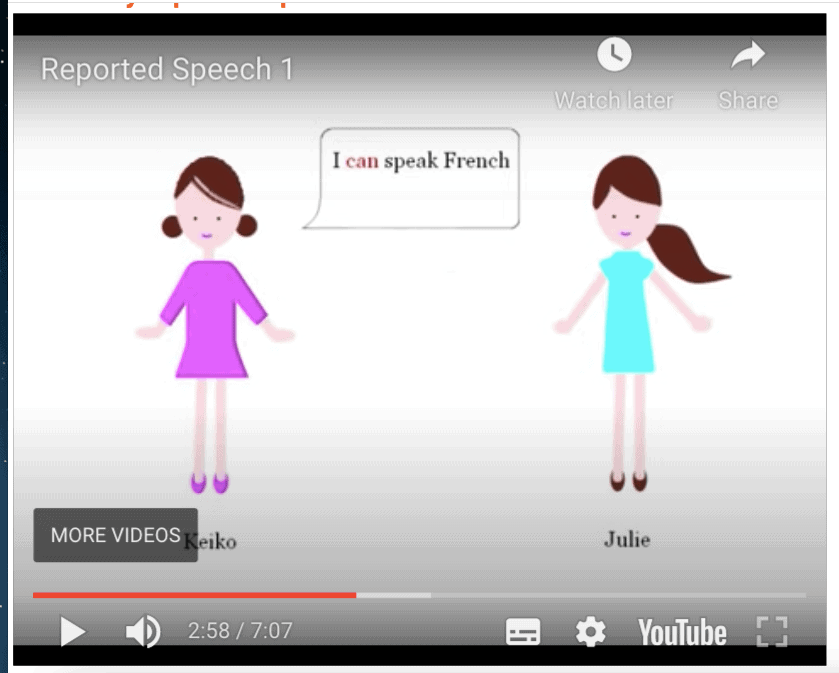

Seonaid shot herself in the foot when she wrote the nonsense above.

If somebody can speak French one day, they can probably speak it tomorrow (sorry, the day after!) as well.

In my view, Keiko said she can speak French rolls off the tongue very naturally indeed. Why even transform can to could? Why on earth would “we” change the tense?

Seonaid’s views are so contradictory. One moment, we “don’t need to change the present tense into the past”. The next moment, “even then usually we like to change the tense”.

Later on in the video, Seonaid produced more grammar nonsense in relation to past tenses:

1. Sometimes we can choose if we change the tense or not

2. Past Simple can stay Past Simple

3. Keiko: “I bought a car”

4. Julie to John: “Keiko said she bought a car”

5. Or: Past Simple can change to Past Perfect

6. Keiko: “I bought a car”

7. Julie to John: “Keiko said she had bought a car”

Frankly, I can’t believe the author has produced all this nonsense without giving an explanation as to why “we can choose if we change the tense or not”.

When choosing how to transform a past simple, does it depend on how far back in time the action took place? Does it depend on whether you’re British or American? Does it depend on whether there’s a time reference after a revelation like “I bought a car”, in which case, why isn’t there an explanation in the video?

To my mind, reported speech in the past simple rolls off the tongue:

Keiko said she bought a car

I’m not sure I’d ever report it in the past perfect. Certainly, I’d never correct a student for failing to report something in the past perfect. In fact, I’d congratulate them for avoiding past simple to past perfect backshift because it’s grammar nonsense.

Let’s finish off this part with something from englishclub.com:

Generally, two sound pieces of advice to begin with.

However, I fail to see the reason why anyone would use backshift to mention someone likes coffee. Maybe you would use the past (liked) if there was more context about a time in the past he liked coffee. For example:

He said that he liked coffee back in his mid-twenties when he was doing his PhD

However, as with all those silly reported speech transformation exercises, there is no context here.

Overall, students can forget this nonsense backshift lark when they speak with people in the real world. Of course, they may backshift to their heart’s content in order to pass exams.

(c) Reported speech practice exercises often revolve around transformations of single sentences and interviews you listen to and then report

In (b), I mentioned how “we usually just report the generality of what was said” when it concerns normal indirect speech. (Dellar and Walkley, p.15).

When you think about it, you don’t usually report something to somebody else in a single, short sentence. I think it’s natural to tell a story and elaborate on something somebody else said, especially if it’s news of a revealing or gossipy nature.

Anyway, Delllar and Walkley were once asked about the following sentence in an online discussion:

He definitely said he was a vegetarian

They were asked whether the use of is in “He definitely said he is a vegetarian'' is wrong.

Saying … is a vegetarian might be confusing to a listener if there’s now evidence that the person in question is longer a vegetarian. Problems arise when there’s a lack of context and the entire story is missing. Over to Dellar and Walkey (p.21):

… this is all incredibly dependent on context and the great problem with reported speech teaching is that we almost never have this context. Instead, we’re just given mathematical transformations of single sentences.

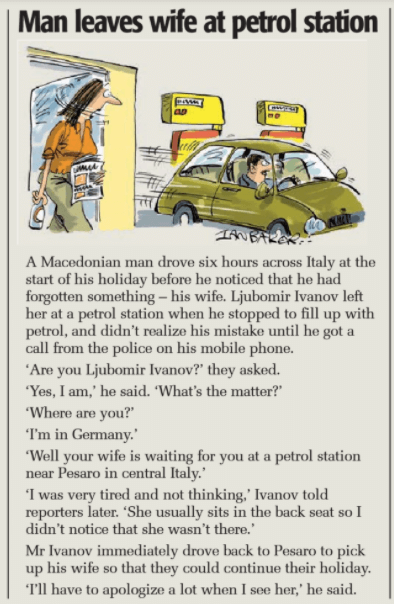

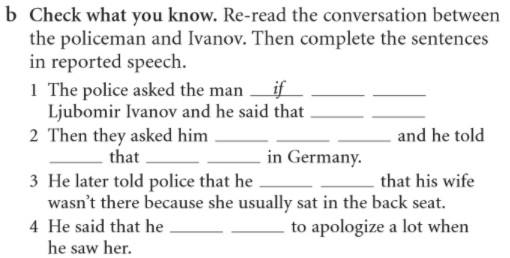

Moving on, Dellar and Walkley have a few gripes with the way reported speech is practised. Namely, it’s nearly always practised as an interview which you listen to [or read] and then report.

Alas, here’s some real drivel I found in an Upper-Intermediate Student’s Book:

You can see where Dellar and Walkley are (were! - sorry) coming from, can’t you?

Who on earth would report a conversation or interview in such a robotic way in the real world?

Who would report such an event using short sentences and so many reporting verbs (asked, said, told) in quick succession?

(d) Establishing a clear difference between what is and what isn’t a reporting verb seems arbitrary

Over to Dellar and Walkley for another flummoxing case or grammar nonsense related to reporting verbs used in reported speech (p.23):

Recently, I had a debate with an editor about which words could be included in a grammar section on reporting verbs. We told that the following were decidedly not reported verbs: decide, intend, avoid, miss and carry on.

The author of chapter 2 goes on to ask a few thought-provoking questions about reporting verbs (p.23):

"How do we know, for example, that [decided in the following sentence isn't a reporting verb:] She’s decided not to come to the wedding after all? Couldn’t the sentence be a report of a whole conversation we’ve had with her? How is refused - as in She refused to come to the wedding - a reporting verb, while decide is not?

In summary, there are plenty of coursebook editors who need to take a long, hard look at themselves for all the grammar nonsense they preach.

2. Stative verbs

Ah yes, that old friend - stative verbs.

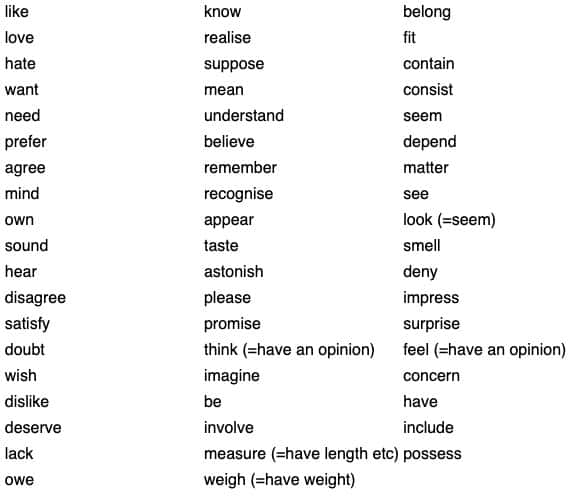

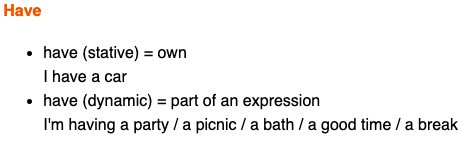

Supposedly, stative verbs cannot be used in the continuous -ing form. For Dellar and Walkley, stative verbs don’t deserve their name nor definition. Essentially, a lot of grammar nonsense derives from the labels that we get sucked into using as ELT teachers. Hence, ‘stative’ is just another label.

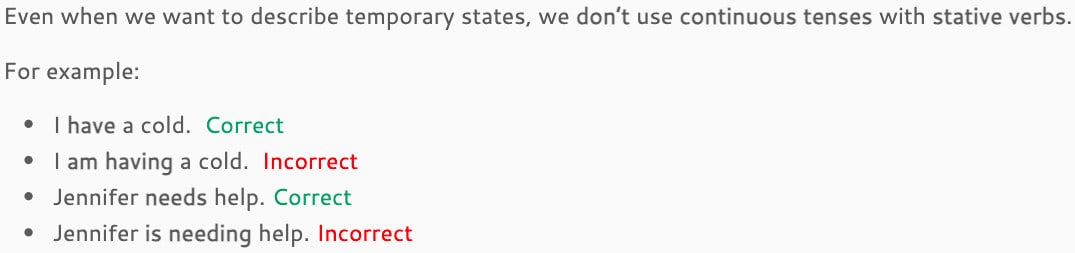

Some teachers take the ‘stative’ label too far

As the two samples below show, some ESL “experts” are living in cloud cuckoo land:

(a) The dreaded list of ‘stative’ verbs

On one website, I found the following list of ‘stative’ verbs:

Source: https://www.perfect-english-grammar.com/stative-verbs.html

The author of this page is clearly prone to churning out grammar nonsense, thus:

Some English verbs, which we call state, non-continuous or stative verbs, aren't used in continuous tenses (like the present continuous, or the future continuous).

Not only is the author prone to grammar nonsense, she shoots herself in the foot in the following section of her post:

Some verbs can be both stative and dynamic

Why is this "grammar expert" so unanimous in her claim that “Some English verbs … aren’t used in the continuous tenses” when she then goes on to concede that “some verbs can be both stative and dynamic”?

(b) Put an end to this obsession with “correct” and “incorrect”

I won’t name and shame the author of this section from a grammar-mad blog post so as not to embarrass him further:

Presumably, he’s never said “I’m having a great time” before when someone asked him how his holiday was going.

Perhaps he would reply to the question about his holiday along the following lines:

I have a really good time. I think about staying another week. Honestly - I have a great time.

Come on, let’s do away with the ‘stative’ label.

Times have changed

So, as you may have gathered, many of the verbs in the dreaded list of ‘stative’ verbs above can actually be used in the continuous form. In fact, they are used in real-life conversation.

As Dellar and Walkley point out, think about the widespread use of I’m loving it (owing to the slogan of a famous fast-food brand).

Here are some other common examples, also inspired by the authors:

So if I’m understanding this correctly …

It’s costing me an arm and a leg!

I’ve been wanting to do it for ages

I was actually agreeing with - I’m sorry if that didn’t come across!

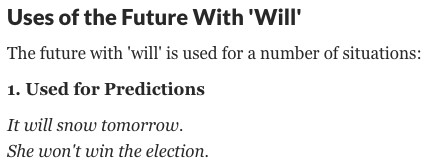

3. Future forms

One more area of grammar nonsense in Dellar and Walkley’s book that I’d like to cover is the dazzling array of future forms many ELT teachers try to “teach” students.

According to Dellar and Walkley (p.62):

The structures used to refer to the future are by no means clearly defined.

Frankly, few native speakers notice so-called ‘mistakes’ related to future forms. For instance, look at the grammar nonsense which surrounds be going to vs the present continuous. Even though both of these structures can be used for planned events, grammar editors still try to pick apart the differences between them. Why even waste time debating the difference between Where are they going to stay when they come? and Where are they staying when they come?

Now, let’s have a look at this post on future forms where there’s yet more plenty of grammar nonsense on show:

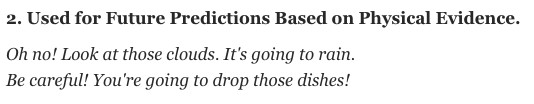

a. Will vs going to

Apparently, will is used for predictions.

All right, so it will snow tomorrow.

Teachers of English - would you really penalise a student for saying “I reckon it’s gonna snow tomorrow”? I don’t think you should. It sounds very natural to say such a thing.

This is just ridiculous. There has to be physical evidence in order to use going to! So, grammar editors, if I can “smell” snow in the air, the clouds are building and it’s freezing outside, do I have to say “It will snow later”? Or have I presented enough physical evidence to say “It’s going to snow later?”

b. Will vs present simple

In the post I linked to above, we “learn” that will is used for scheduled events:

I refute such grammar nonsense. It’s far more natural to use the present simple:

The concert starts at 8

When does the train leave?

Dellar and Walkley rightly gripe about this sentence (p.64):

It’ll take an hour to get to the airport

Do we need to make a prediction? Isn’t it more natural to say “It takes an hour or so to get to the airport?” Presumably, the speaker has gained some previous knowledge about how long it takes to get to the airport. Hence, general truths based on one’s own knowledge might be better off in the present simple.

Of course, we can’t deal with grammatical conundrums without CONTEXT. Remember that word - context. If the speaker has just seen on the news that there’s been a massive accident on the motorway just five minutes away from the airport, then all right, use going to or will:

There’s been a bad accident on the motorway. It’s going to take a good ninety minutes to get to the airport

Then again, perhaps the sight of twenty smashed up cars is not good enough “physical evidence” for the grammar editors. Use will then!

Conclusion - Grammar nonsense is everywhere in ELT

In this post, I’ve only scratched the surface with regard to the sheer diversity of grammar nonsense Dellar and Walkley assess.

I could have also discussed, for example, relative clauses and the teaching of auxiliaries in short answers, both grammar nonsense topics which Dellar and Walkley also dealt with very astutely.

Anyhow, here are the main takeaways from Grammar Nonsense:

- Teach grammar lexically - Teach words with the grammar they’re often used with and through examples. In this way, “we increase the number of repeated encounters students have with ‘old’ words and grammar compared to what we would do if we focused more on just the grammar rule or form.” (p.99).

- Context, context, context - It’s unfair to correct students when we dish out exercises in the form of transformations of single sentences. We need to have a true natural context for each sentence. Unfortunately, when it comes to coursebooks, grammar gets removed from its context and is heavily processed so as to illustrate a particular ‘rule’

- Teachers have to rise up against grammar nonsense - Teachers should talk directly to publishers, examining bodies, and policy makers about absurd grammar rules that are perpetuated through both books and exams. Publishers often refer to the need to ‘cover’ grammar, such as reported speech. However, maybe they wouldn’t if more teachers complained to them about such grammar nonsense

I haven’t taught reported speech, passive tenses, relative clauses, stative verbs and the various future forms for over ten years.

All I’m interested in is getting students to work with authentic materials and acquainting them with typical chunks and multi-word items that typically crop up in real everyday conversations.

Don’t worry - useful grammar patterns emerge naturally within sentences that contain all these multi-word items.

A matter of emphasis

Finally, it's my impression that Dellar and Walkley label certain grammatical items as "nonsense" because their overuse or confusion with another similar item rarely lead to critical misunderstandings.

Feasibly, the authors might have included the topic of gerunds (-ing forms) and to-infinitives in their book. However, it's not always about the ease with which a listener comprehends an utterance when it comes to these similar sets of grammatical items. More crucial, perhaps, is the emphasis a speaker wishes to convey with a specific utterance. For instance, I hate reading carries a lot more attitude than I hate to read. The latter is perhaps more suitable when it comes to profiling situations that are likely to occur on a more regular basis. For example:

I hate to read in the morning before I go to school

Reference:

Dellar, H., and Walkley, A. 2020. Grammar Nonsense and What To Do about It, Eugene, OR: Wayzgoose Press