The Whys and the Hows of Becoming an Independent Language Learner

If you’re committed to becoming an independent language learner, you’re in the right place.

This post explores what independent language learning is (and isn’t).

Furthermore, I will go into the role language learning strategies play in autonomous learning and achieving communicative competence (i.e. fluency).

What is Independent Second Language Learning?

A number of principles underpin independent language learning, as Cynthia White (In Hurd and Lewis, 2008, p.3) writes:

– optimising or extending learner choice, focusing on the needs of individual learners, not the interests of a teacher or an institution, and the diffusion of decision-making to learners.

Frankly, it would be too narrow-minded of me to claim that independent L2 (second language) learning is the learning of an additional language without the involvement of a teacher.

That is not the case at all.

Nor is it the case that independent learning cannot be implemented in the classroom. Language teachers do not have to spoon feed students with rigidly structured lessons. Instead, they should function as guides and mentors who can assist language learners in reaching very clear goals.

Finally, White (In Hurd and Lewis, 2008, p.5) firmly equates independent language learning with the development of learning strategies. Therefore, The standout theme in this post is the role that language learning strategies play in independent learning.

Why should you rely less on language teachers?

I’ve been teaching English for nearly sixteen years. Naturally, I have to argue that being immersed in a learning environment which is directly mediated by a teacher has its benefits. Many learners find it extremely motivating to attend a language school and be surrounded by like-minds in a group.

Unfortunately, many language learners are inclined to believe that attending a language school twice a week will eventually lead them out of intermediate-level mediocrity towards a state of advanced-level fluency. This is misguided thinking.

Don’t get me wrong. When I started learning Serbian online with a teacher from Belgrade, I have no doubt that the materials she presented me with, and the exercises we did together, gave me a thorough grammatical grounding in the language. Essentially, it was an education which revealed the logic of the Serbian case system to me.

Nevertheless, there comes a time when you have to lessen your reliance on your teacher and private language schools, and begin to take responsibility for your learning.

In my experience as both a language learner and English language teacher, I’ve learned that becoming a more autonomous language learner can set you on the path to communicating in English EFFORTLESSLY.

Effortlessness in communication arises from implementing studiously-honed methods and language learning strategies to enable you to automatically retrieve grammatical structures, words and collocations in future conversations.

I adopted my Word-Phrase Table strategy to record new words and lexical chunks that I met in printed materials. Moreover, I picked up many lexical items in Serbian through communicating with native speakers and my wife and early on in our relationship. Listening intently to conversations going on around me also helped me to pick up the language very quickly.

I’ll briefly go into the ins and outs of the Word-Phrase Table strategy later on in this post.

What is Communicative Competence?

Before I describe the various categories of language learning strategies language learners can benefit from, it’s first of all vital to realise the end goal of familiarisation with, and the adoption of, language learning strategies.

To be specific, all appropriate language learning strategies are designed to achieve the broad goal of communicative competence (Oxford, 1990, p.8).

When it comes to defining what communicative competence actually is, Canale and Swain (1980) came up with a four-part definition of communicative competence. Here’s a brief summary of the four categories:

1. Grammatical competence:

Grammatical competence is the extent to which the language user has mastered vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar and word formation.

2. Sociolinguistic competence:

Sociolinguistic competence refers to the degree to which utterances can be applied or comprehended appropriately in various social contexts. It includes knowledge of speech acts, such as persuading and apologising.

3. Discourse competence:

Discourse competence is the capacity to combine ideas to go beyond the single sentence and achieve coherence in one’s thoughts.

4. Strategic competence:

Strategic competence is the ability to use strategies such as gestures and paraphrasing of an unknown word in order to compensate for one’s lack of language knowledge.

Clearly, achieving communicative competence demands that you do a great deal more than memorise words and complete grammar gap-fill exercises in grammar practice books.

Overall, you need to be able to fall back on a wide range language learning strategies to achieve overall communicative competence.

What Role do Language Learning Strategies Play in Independent Learning and Achieving Communicative Competence?

It should already be apparent that becoming an independent language learner and achieving communicative competence are lofty goals which depend on your commitment to adopting language learning strategies.

Oxford (1990) proposes two main groups of language learning strategies:

- Direct strategies - involving the target language

- Indirect strategies - for the general management of learning

Allow me to assess these two groups of strategies in a little more detail by looking at the various sets of strategies they comprise.

Direct strategies

Direct strategies refer to the specific actions language learners take to enhance their knowledge of the target language. Oxford (1990, p.37) stated that “All direct strategies require mental processing of the language”.

According to Oxford (1990, pp.37-38), there are three groups of direct strategies. Those are Memory strategies, Cognitive strategies and Compensation strategies.

Let’s scrutinise the three sets of strategies one at a time:

Memory strategies

Memory strategies, also known as mnemonics, have been around for thousands of years.

It’s amazing to think that the mind can store some 100 trillion bits of information. However, unless the language learner does not employ memory strategies, only a tiny part of that potential can be exploited.

Memory strategies in language learning tend to revolve around pairing different types of material. For instance, it’s possible to create visual images of words or phrases. It’s vital to link the verbal with the visual as the mind’s storage capacity for visual information is much greater than its capacity for verbal material (Oxford, 1990, p.40).

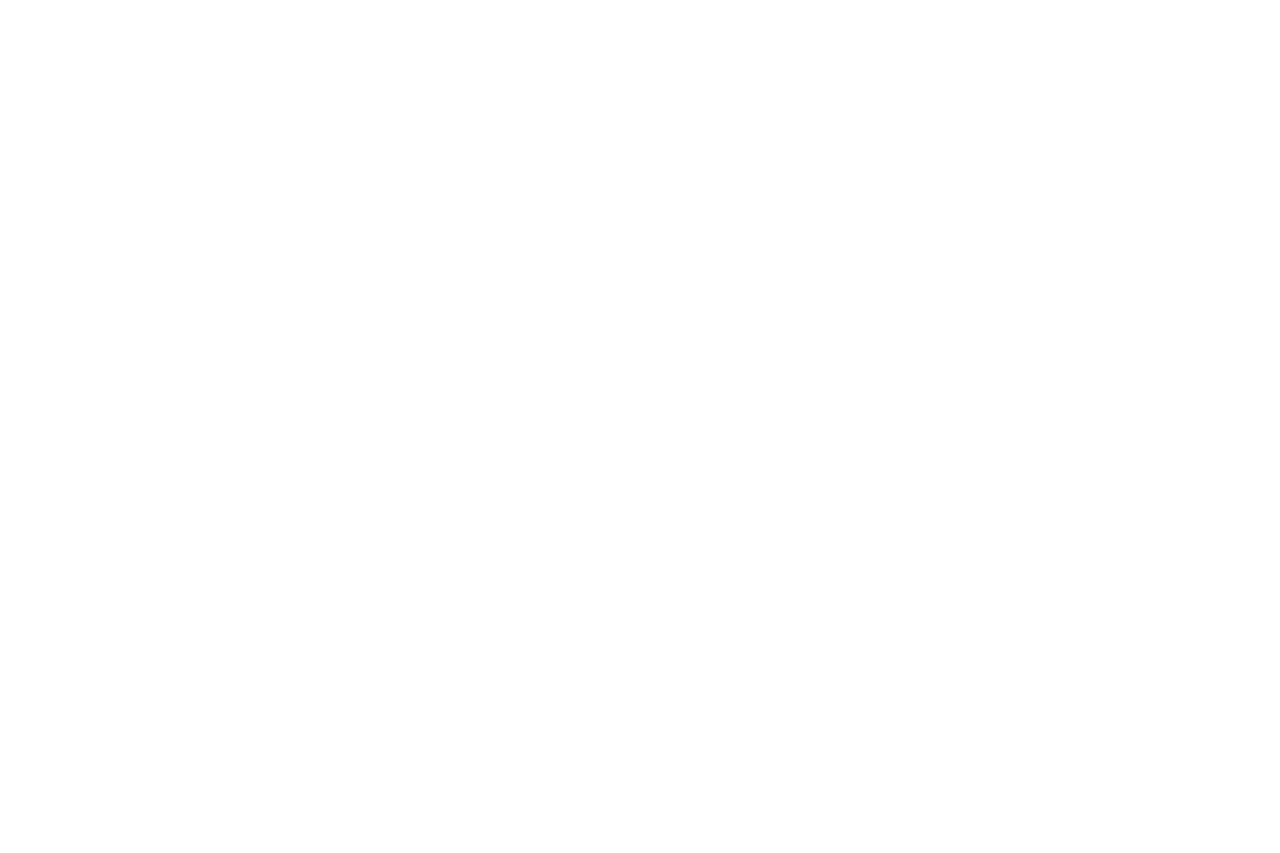

Memory strategies (Oxford, 1990, p.39)

As the diagram above shows, Oxford (1990) broke down memory strategies into four sets which each contain between one and four language learning strategies:

A. Creating mental linkages

1. Grouping

Essentially, grouping involves classifying or reclassifying language material into logical units, either in writing or mentally.

You can create groups based on:

- Topic - e.g., words about weather

- Word class - nouns, verbs, adjectives etc

- Feelings - e.g., like, dislike

- Practical function - e.g., terms for car parts

- Linguistic function - e.g., demand, apology, request

- Similarity - e.g., hot, warm, tropical

- Dissimilarity - e.g., friendly/unfriendly

As second-language vocabulary acquisition experts Diana and Norbert Schmitt (1995, p.137) pointed out, it’s recommended to avoid placing words which are similar to each other in these groupings until they are familiar enough not to be cross-associated.

2. Associating/Elaborating

In essence, the independent learner relates new language information to familiar concepts already stored in memory, or relating one piece of information to another in order to create associations in memory.

These associations may be simple or complex, unoriginal or strange, but they must be meaningful to the learner.

There are countless ways to create associations in memory. For example, Oxford (1990, p.41) mentions multipart “development”, such as school-book-paper-tree-country-earth. It’s also possible to associate a second-language word with a word that sounds similar in one’s first language. For instance, Oxford (1990, p.60) cites the case of Glennys who associates the Russian word soyuz (union) with the name of her friend - Susie.

3. Placing new words into a context

This strategy involves placing new words or expressions into a meaningful sentence, conversation, or story in order to aid memory.

Oxford (1990, p.60) refers to the example of Katya, a learner of English, who comes across a list of words and expressions connected with sewing. Some of these words include hook, eye, seam, button, thread, needle, hem and stitch. Katya writes a story so as to place these words into a meaningful context.

B. Applying images and sounds

1. Using Imagery

Many independent language learners tie newly learned language information to concepts in memory through meaningful visual imagery, either in the mind or in an actual drawing.

Oxford (1990, p.61) describes the case of Adel, a Spanish bank manager learning English, trying to remember the phrase tax shelter. Adel uses a mental image of a small house sheltering a pile of money inside.

As for drawings, they have the effect of making mental images more concrete. For instance, learners can draw diagrams with arrows to illustrate meanings for prepositions such as above, under, into and between.

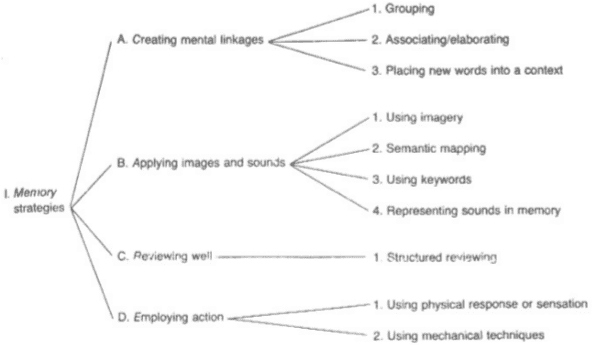

2. Semantic mapping

Semantic mapping involves making an arrangement of words into a picture to visually show how certain groups of words are interconnected. The key concept, such as HAIR in the diagram below, is added to the centre or at the top of the map. Related words and concepts are linked with the key concept by means of arrows or lines:

Example of a Semantic Map for "Hair. (Source: Brown-Azarowicz, Stannard, and Goldin (1986, p.32) In Oxford, 1990, p. 64)

Semantic mapping encompasses a range of other memory strategies such as grouping, associating/elaborating and using imagery overlap.

3. Using keywords

Richard Atkinson and Michael Raugh (1975) described the essence of the keyword method thus:

The method used divides the study of a vocabulary item into two stages. The first stage requires the subject to associate the spoken foreign word with an English word, the keyword, that sounds like some part of the foreign word; the second stage requires him to form a mental image of the keyword interacting with the English translation. Thus, the keyword method can be described as a chain of two links connecting a foreign word to its English translation through the mediation of a keyword: the foreign word is linked to a keyword by a similarity in sound (acoustic link), and the keyword is linked to the English translation by a mental image (imagery link).

Here’s an example of how to apply the keyword method with reference to my potential learning of Polish vocabulary related to driving and car parts:

Stage 1:

- Polish word = silnik / English word = engine;

- The keyword could be the English word shield (i.e. a piece of personal armour). Shiel broadly sounds like ‘sil’ - the first three letters of the Polish word for engine. Hence, an acoustic link has been established;

Stage 2:

- Now, I must form a mental image of the keyword interacting with the English translation. With shield and engine, the most obvious imagery link would be a shield resting upright on top of an engine.

Overall, the keyword technique may appear to be complex or extravagant. However, it should not be discounted for its ability to help language learners remember, for example, standalone words where little context is available. After all, a fundamental part of becoming an independent language learner is the addition of multiple and highly varied strings to one’s bow when it comes to attempting to memorise a word or group of words.

4. Representing sounds in memory

With this strategy, learners make auditory as opposed to visual representations of sounds in order to remember what they hear.

The main tenet of the approach is to link the work with familiar sounds or words from one’s mother tongue, the target language, or any other language.

For example, a learner of English may make up nonsense rhymes to help them remember the sounds of English words, such as coat, float, mote, dote, boat and goat.

In another example, David encounters the English word familiar in an article. It sounds like a word he already knows, family. Hence, the auditory link enables David to remember the new word.

C. Reviewing well

In this category, there’s only one strategy - structured reviewing. It’s vital to review new target language at regular interviews in order to remember it. Structured reviewing, as Oxford (1990, p.42) refers to it, is contemporarily known as spaced repetition.

Structured reviewing

Essentially, it’s vital to review a new word or phrase at an interval that’s not too distant from the point of contact with that language item. For example, structured reviewing might begin with a review 10 minutes after first contact. Then, a review might take place 20 minutes later, an hour later, three hours later, a day later, 2 days later, a week later, and so on.

I will explain how this method helped me to memorise Serbian words and collocations later on.

Overall, the goal is “overlearning”. In other words, you become so familiar with the information that retrieval eventually becomes automatic.

D. Employing action

1. Using Physical Response or Sensation

Physically acting out a new expression (e.g., opening the window), or relating a new expression to a physical feeling or sensation (e.g., cold).

Oxford (1990, p.66) describes the example of a learner of German who trains himself to get a physical feeling of heat when he comes across a new feminine noun, a feeling of cold for a masculine noun, and a feeling of moderate temperature for a neuter noun.

2. Using mechanical techniques

In order to remember new target language information, the independent learner can use separate sections of their vocabulary notebook according to whether words have been learned or not.

Based on a similar principle, physical flashcards can be moved from one pile to another depending on the learner’s familiarity with the content.

Cognitive strategies

Cohen (2011, p.19) convincingly defines cognitive strategies thus:

Cognitive strategies deal with the crucial nuts and bolts of language use since they involve the awareness, perception, reasoning, and conceptualizing processes that learners undertake in both learning the target language (e.g., identification, grouping, retention, and storage of language material) and in activating their knowledge (e.g., retrieval of language material, rehearsal, and comprehension or production of words, phrases, and other elements of the target language).

Clearly, there are overlaps between cognitive strategies and memory strategies. Norbert Schmitt admitted that the goal of both groups of strategies “is to assist the recall of words through some form of language manipulation” (Schmitt, 1997, p.205). However, Schmitt went on to separate the two classes of categories. He categorised those strategies which are “less obviously linked to mental manipulation (repeating and using mechanical means)” as cognitive. Paradoxically, memory strategies are those “closer to traditional mnemonic techniques …” (Schmitt, 1997, p.206).

Becoming an independent language learner largely revolves around the efficient application of cognitive strategies to the four language skills. I will now highlight three useful cognitive strategies, as put forward by Oxford (1990):

1. Repeating

Falling under the category of practicing, one strategy worth pursuing is repeating.

Although the idea of repeating doesn’t sound glamorous, it can be used in highly innovative ways.

For instance, imagine listening to the weather report in a second language every day. After some time, you will become familiar with a multitude of weather-related terms.

The strategy of repeating might also entail reading a passage several times in order to achieve a more thorough comprehension of it. Another worthwhile technique is to read a passage several times, each time for a different purpose. For instance, the first reading should be to get the general drift, while further readings could be to read for detail and to make predictions regarding plot development. The final reading might be reserved for writing down any language-related questions you may have.

2. Analysing expressions

Falling under the umbrella of Analysing and Reasoning, the strategy of Analysing expressions encourages learners to break down a new word, phrase or sentence, into its component parts.

Admittedly, the strategy is more useful for reading than it is for listening as readers have more time to go back and analyse complicated expressions. It’s difficult to analyse or even note down an expression in the heat of a conversation.

However, if you hear an unfamiliar phrase on a TV news broadcast, jot it down. Oxford (1990, p.83) gives the example of Martina who hears the phrase premeditated crime on the news. The learner breaks down this phrase into parts that are known to her:

- crime = bad act

- meditate = think about

- pre- = before

Therefore, Martina deduces the meaning of premeditated crime as an evil act that is planned in advance.

3. Highlighting

Learners very often benefit by supplementing notes through the strategy of highlighting.

In a language learning context, you can use colour, underlining, capital letters, big writing, bold writing, stars, circles, and so on, in order to highlight various kinds of information. This information includes vocabulary and grammar points.

Compensation strategies

The final group of direct strategies is compensation strategies.

Compensation strategies, often referred to as guessing strategies, chiefly involve using linguistic clues to guess the meaning of unknown expressions.

To my mind, if you are willing to guess intelligently in listening and reading, it’s a sign that you’re well on the way to becoming an independent language learner. Simply, you need to banish the belief that you have to understand every single word before you can comprehend the overall meaning of a spoken utterance or written sentence.

Without complete knowledge of grammar, vocabulary and other target language elements, you should use language-based clues to help you guess the meaning of what you hear or read in the target language. It’s very often the case that your own language, previously gained knowledge of the target language or even another language can provide linguistic clues to the meaning of what is read or heard.

Oxford (1990, p.91) provides some revealing examples of guessing based on limited knowledge of the target language. Take, for example, the learner of English who recognises the English words mower, lawn, shovel and grass. This learner deduces that the conversation is about gardening.

As for knowledge of the mother tongue to work material heard in the target language, assess the case of Frank, whose knowledge of English enables him to guess that J’arrive! (French) means I’m coming.

Indirect strategies

Becoming an independent language learner doesn’t solely revolve around what you do with the target language. You have to implement strategies to manage language learning. These strategies may fall into two groups:

1. Metacognitive strategies - help learners to focus, plan and evaluate their progress as they strive toward communicative competence.

2. Affective strategies - help learners to manage emotions, both positive and negative.

I will now describe one strategy from each of those groups which I feel are quite obvious, yet they are still overlooked by many independent language learners:

1. Organising (metacognitive)

This strategy incorporates a range of tools, such as keeping to a schedule, creating the best possible physical environment, and keeping a language learning notebook.

First, in order to develop your language skills, you need to have an appropriate physical environment. After all, how can you listen and read when there’s too much background noise?

Second, you need to develop a weekly schedule for language learning. Skills such as writing and reading are generally best developed with unbroken stretches of time. It’s vital to build some relaxation time into your schedule.

Finally, as Oxford (1990, p.156) points out, you should make use of a language learning notebook. Utilise the notebook to record new target language structures and expressions in the contexts they were encountered. Furthermore, you can use the book to note down any strategies which work well, areas of the target language you’re struggling with and your goals and objectives.

2. Making positive statements (affective)

Belonging to the category Encouraging yourself (Oxford, 1990, p.143), the affective strategy I would like to elaborate on is making positive statements.

Essentially, this strategy revolves around writing or saying positive statements to oneself. The aim is to boost confidence levels when it comes to learning the new language.

Although Oxford (1990, p.165) encourages teachers to say positive statements to themselves primarily before a potentially tricky language activity, I still believe there’s room for independent language learners to write or say statements as part of their personal daily, weekly or monthly progress reviews.

Examples of positive statements include:

I enjoy understanding the new language.

I had a very positive and inspiring conversation today.

I’ve noticed that my fluency is increasing.

I’m taking risks and doing well.

It’s OK if I make mistakes.

Overall, a key part of becoming an independent language learner is self-encouragement. I’m sure it’s one of the key factors separating those stuck at an intermediate level of a foreign language, and those who overcome the intermediate plateau to become competent advanced-level speakers.

The Trusty Word-Phrase Table

In the opening section of this post, I mentioned the strategy which helped to propel me to a more advanced state of spoken fluency in Serbian.

For me, becoming an independent language learner was synonymous with updating my Word-Phrase Table on a regular basis.

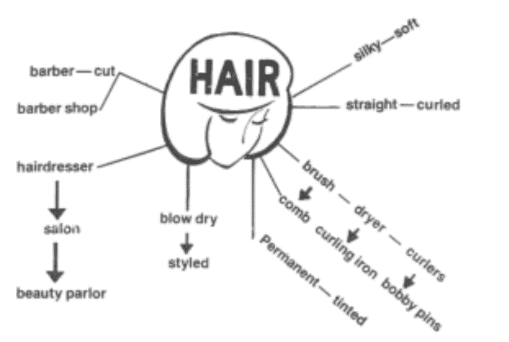

Word-Phrase Table entry for the verb 'travel'

With reference to the direct and indirect strategies I outlined in previous sections, it’s plain to see that I relied on organising (a metacognitive strategy), structured reviewing (a memory strategy), and highlighting (a cognitive strategy):

Organising my Word-Phrase Table

After some time learning Serbian, I set out to record new target language structures and expressions, most often in the contexts they were encountered. However, I didn’t use a physical language learning notebook, as Oxford (1990, p.156) recommends. Times have changed since 1990.

It was very convenient for me to use a Google Doc to keep things neat and tidy. Moreover, it’s easier to update existing entries on a web-based editor than it is in a language learning notebook. This is because it’s impractical to leave extra space or pages in a notebook to add new information. In addition, making changes to entries at a later date can get messy.

Structured reviewing of lexical items

In light of what I wrote earlier in the post about structured reviewing, I personally wasn’t so rigid with the intervals at which I’d review a new word or phrase.

In fact, I usually reviewed an entry the day after adding it to my Word-Phrase Table. After that, I tended to review information two days later, then three days later, then five days later, and so on.

My own approach wasn’t that suggestive of “overlearning”. Nevertheless, the fact I tended to avoid structured reviewing during the first 18-24 hours didn’t have an impact on my ability to recall the target language information.

Highlighting language information in my Word-Phrase Table

As previously mentioned, various methods exist to highlight different kinds of information.

In the entry in the table, notice that I have used:

- Capital letters - to highlight a grammar point (e.g. po + locative; po Americi = around America - I’d love to travel around America)

- Big letters - to highlight verb forms

- Stars (*) - personalised sentences (sentences that are about me, someone I know, a personal opinion, or reflect my current situation in life)

- Dashes (-) - collocations and phrases containing the target word

- Plus sign (+) - related verbs

In my Word-Phrase Table, the highlighting methods I used didn’t always follow the same logic from entry to entry. Just because I have used big letters for the verb forms above (putovati - to travel; putovao - travelled; (da) putujem - literally ‘that I travel’ ), it doesn’t mean I would apply the same highlighting methods in the next entry.

I always felt that each entry, along with its accompanying linguistic information, needed to have its own individual appearance. This is because visualisation and memorisation very much go hand in hand.

Final reflections on independent language learning

The reason I’ve devoted the majority of this post to language learning strategies is because their use reflects and promotes learner autonomy.

However, it is wishful thinking to expect language learners to wave a magic wand and begin to use language learning strategies. For many language learners, the process of adjustment from teacher-mediated language classes to distance learning, or independent learning, can be a painful one. So many factors can affect the language learner’s willingness to adopt strategies autonomously. These considerations include motivation levels, cultural influences, personality traits and psychological factors.

Overall, becoming an independent language learner is a worthwhile and rewarding journey. Do remember, though, that independent language learning does not have to be teacherless.

References

Atkinson, R.C., & Rough, M.R. (1975). An Application of the Mnemonic Keyword Method to the Acquisition of a Russian Vocabulary. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, Vol.104, No.2, 126-133

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical Bases of Communicative Approaches to Second Language Teaching and Testing. Applied Linguistics, Vol.1, No 1, 1-47.

Cohen, A., (2014). Strategies in Learning and Using a Second Language, Second Edition, Abingdon, UK: Routledge

Oxford, R., (1990). Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know, Boston: Heinle and Heinle Publishers

Schmitt, N. (1997). Vocabulary Learning Strategies. In Schmitt, N., & McCarthy, M. (Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, Acquisition and Pedagogy (pp.199-227). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schmitt, N., & Schmitt, D. (April 1995). Vocabulary Notebooks: Theoretical Underpinnings and Practical Suggestions. ELT Journal, 49 (2), 133-143

White, C. (2008). Language Learning Strategies in Independent Language Learning: An Overview. In Hurd, S., & Lewis, T. (Eds.), Language Learning Strategies in Independent Settings (pp.3-24), Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters