Choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives after main verbs

This post tackles the very thorny issue of choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives. Although there are some rules which govern the use of gerunds and to-infinitives, only a great deal of practice and exposure to English may enable the learner to retrieve the right form when they are the object of a sentence (i.e. follow a main verb).

Before I explore the differences between gerunds and to-infinitives, I will first of all define what they are.

What is a Gerund?

Gerunds comprise the base form of a verb (bare infinitive) followed by -ing.

The most defining feature of gerunds is that they behave entirely as nouns, despite the fact that they’re derived from verbs.

An example of a gerund is the word cycling. Hence, we can use the word cycling in a sentence as a noun to refer to the act of riding a bike, as in:

Cycling is good for your health

I love cycling

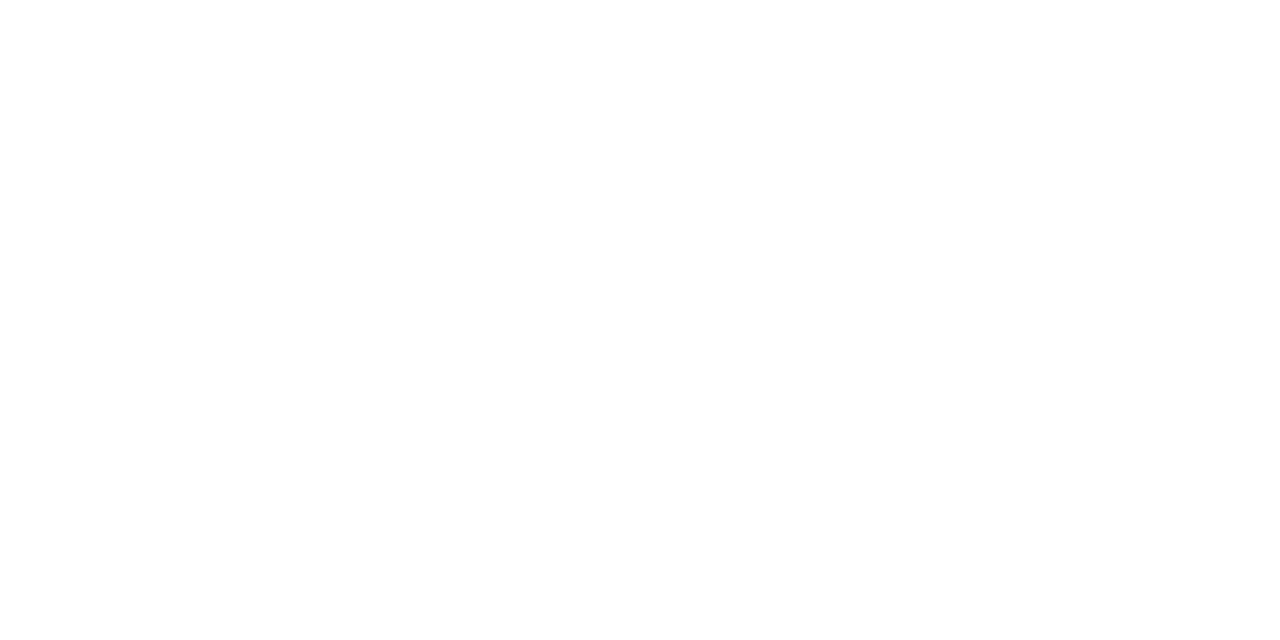

The word cycling retains its verbal characteristic. However, the role this gerund plays shifts from describing the action to being a focal point. Essentially, cycling becomes a thing, in that it can be the subject or direct object of a sentence. Nevertheless, the buck doesn’t stop with these two kinds of gerunds. Check out just how versatile gerunds are:

It’s important that the learner does not confuse gerunds with present participle verbs. Present participle verbs describe the action in a sentence, as in:

As I was walking to work, I tripped over the kerb and broke my news

I am sleeping

What is a to-infinitive?

To-infinitives, also known as full infinitives, are formed by taking the base form (bare infinitive) form of a verb and adding to in front of it.

To-infinitives are used in many situations, including to show intention and after relative pronouns, such as how and what.

The to-infinitive in the following sentence acts as an adverb (of purpose) to describe the main verb:

Mum just left to buy some bread

Paving the way to choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives

Deciding on whether to use a gerund or to-infinitive can be exceptionally difficult for learners of English. This is because there are so many verbs which can co-occur with both forms, depending on the context of course.

Parrott (2000: 170) points out that it's hard to make a choice between a to-infinitive or gerund because the “rules which guide us may seem arbitrary to learners.”

With Parrott’s (ibid.) point in mind, I will now reveal some of the most defining features of gerunds and to-infinitives. I am able to do this because I have researched how both authors of generic grammar guides and specialists on infinitive and -ing clauses typically distinguish between the two forms.

1. The forward and backward-looking qualities to-infinitive and -ing forms

Two authors who describe what a to-infinitive and an -ing form tend to express are Parrott (2000) and Close (1992).

First of all, both authors concur that a full infinitive implies looking forward in a series of events. To fully appreciate the dominant forward-looking qualities of the infinitive, one must respect the general consensus among scholars that the origins of the to of the infinitive derive from the preposition to (Egan, 2008, p.95). Hence, to is a variant of the preposition and it, therefore, represents a ‘path towards goal’ function. The potentiality of an event obviously plays a role here.

Anyway, if the full infinitive refers to the future, or a new act in a chain of events, then the -ing should logically look “backwards to previous activity in progress or even to a previous act completed” (Close, 1992: 122).

Close (ibid.) provides three pairs of sentences which capably highlight how the -ing refers to a process on which the speaker is looking back. Conversely, the infinitive refers to a new (forward-looking) act:

1.

(a) I remembered to telephone the doctor.

(b) I remembered telephoning the doctor.

Here, (a) means: First I remember what I had to do, then I called. (b) means: I telephoned the doctor, and remembered doing so.

2.

(a) I usually forget to sign my letters.

(b) I shall never forget seeing Fujiyama by moonlight.

Here, (a) suggests that I forget that I have to sign my letters and therefore do not sign them. In contrast, (b) suggests that I shall not forget an event which occurred in the past.

3.

(a) I regret to tell you that I shall be away.

(b) I regret telling you that I shall be away.

In (a), I first regret and now I tell you. In (b), I have already told you, and now I regret it.

Finally, it’s important to state that there are plenty of cases whereby the gerund has forward-looking qualities. Aided by the work of Egan (2008), I will explore some of these cases later on in this post.

2. Activity in progress or new act

Close (1992: 120-21) stresses the point that the -ing form may refer to activity in progress. On the contrary, the full infinitive refers to a new act in a chain of events. This distinction, then, is partially related to the backward-looking/forward-looking variance outlined in part 1 above.

The examples Close (p.122) provides are:

(a) I like dancing. (= the activity)

(b) Would you like to dance? (a new act)

However, it’s also possible to say I like to dance. I have also explored the distinction between like with -ing and like + to-infinitive so be sure to check out that post.

3. Different-subject constructions

As the title suggests, different-subject (DS) constructions contain two subjects (Egan, 2008: 20). In different-subject constructions, the subject of the main verb (S1) is distinct from the subject of the complement predicate (S2).

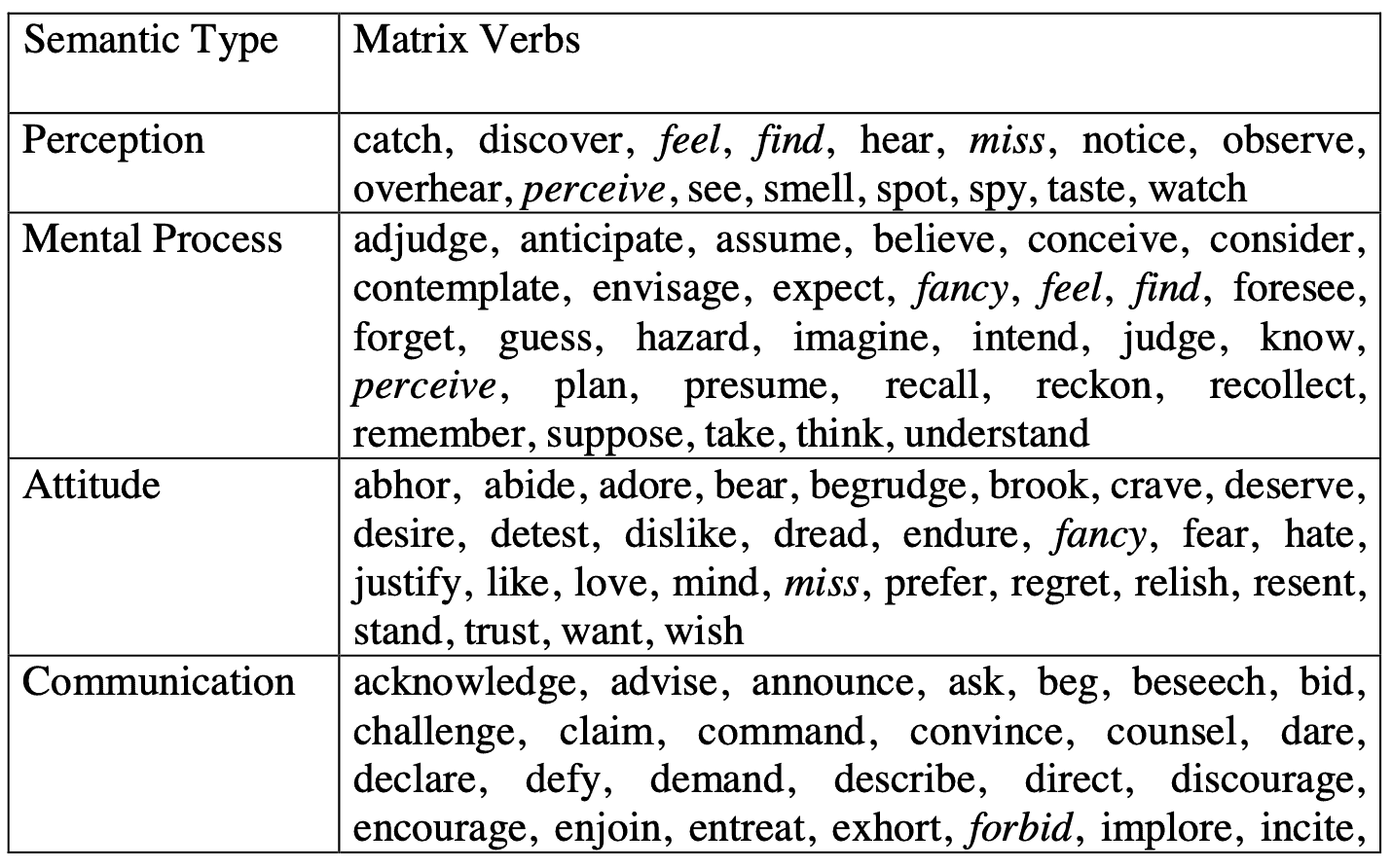

Egan (2008: 22-23) proposes six categories of different-subject constructions:

(1) Perception constructions

S1 registers the action taking place. For example:

You noticed me watching you, I shouldn’t wonder …

(2) Mental Process constructions

S1 registers the action taking place, considers it and may form a judgement regarding its existence. For instance:

Most scientists believe the infill to be lava.

(3) Attitude constructions

Here, S1 registers the action in progress and formulates an attitude towards it. For example:

I dread mine reaching their teens.

(4) Communication constructions

S1 issues advice to S2 or instructs the onstage S2 to take action. For instance:

The master commands you to stay.

It’s worth noting that, in a minority of communication constructions, the addressee of the communication is not S2.

(5) Enablement constructions

S1 either sets the stage for S2’s realisation of the complement clause situation or assumes the role of a minor character in helping S2 to realise it. For example:

Outside he allowed her to examine the bird.

(6) Causation constructions

S1 directs the realisation of the complement clause situation by S2, who has no independent say in the matter. For instance:

He halted, forcing the rest of the field to bunch up behind him.

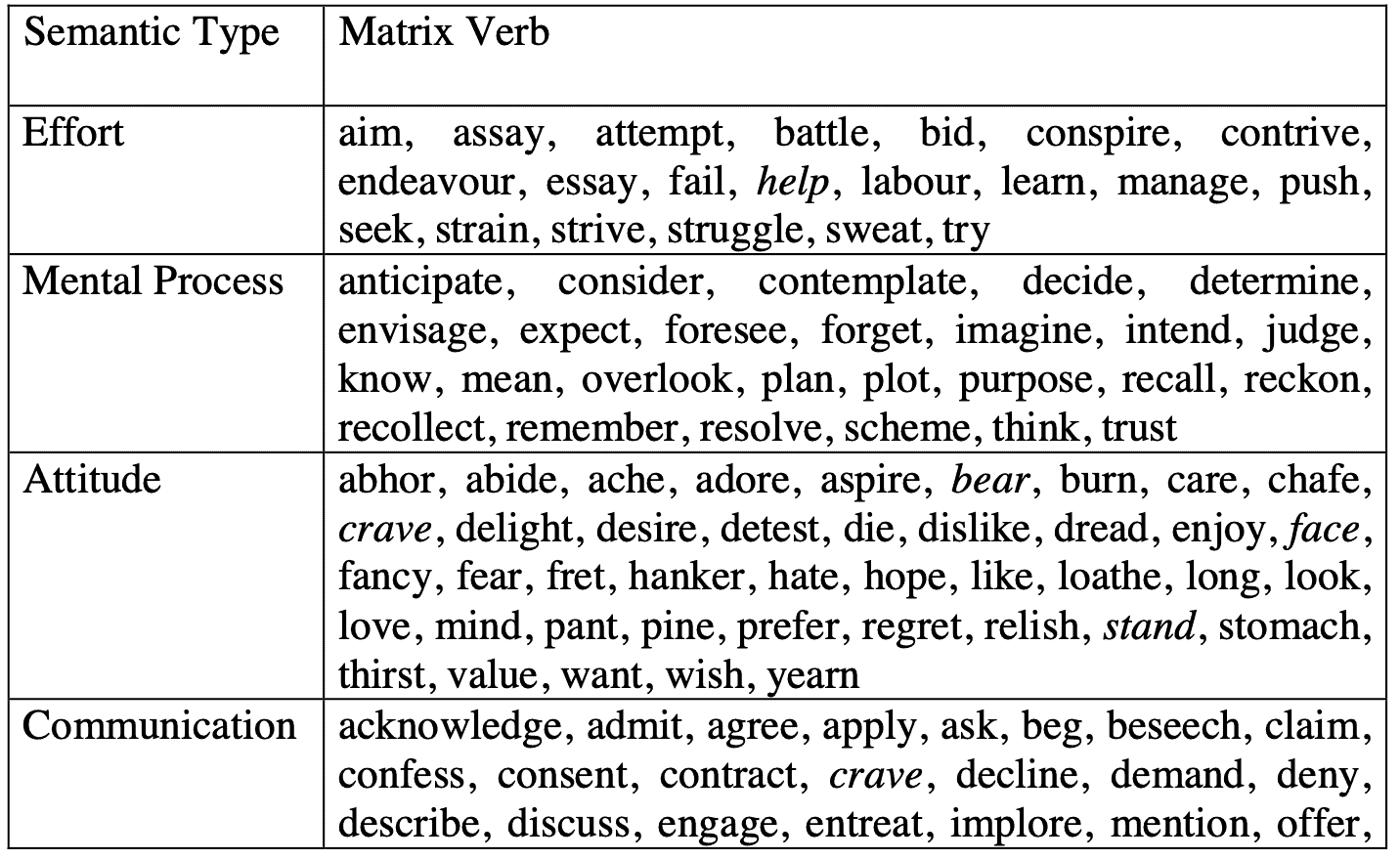

Below is a comprehensive (though not exhaustive) list of all the main verbs covered in Egan’s particular study belonging to each category for different-subject to-infinitive and -ing constructions. (in Egan, 2008: 25-26):

* Verbs listed twice are in italics

4. Same-subject constructions

Same-subject (SS) constructions comprise just one subject. In the following sentence, He is both the subject of vowed and of challenge:

He vowed to continuously challenge the government.

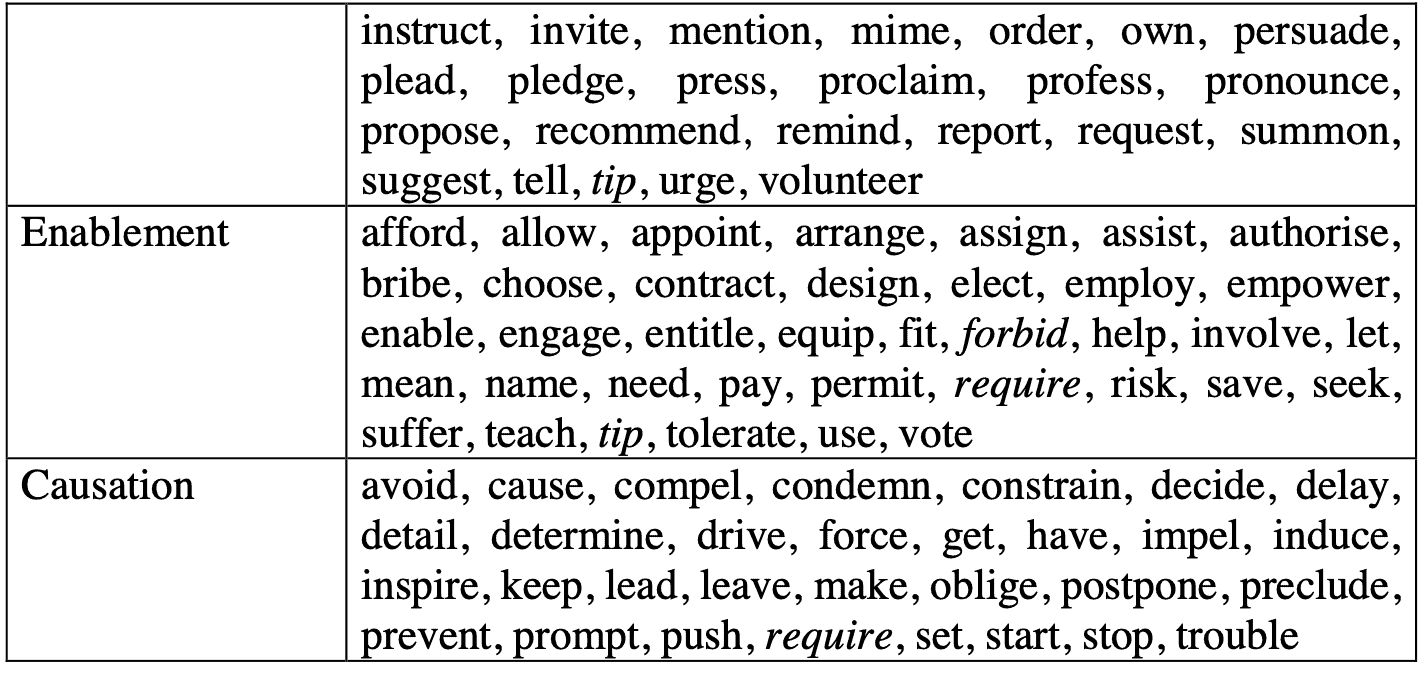

As with different-subject constructions, Egan (2008: 26-27) proposes six categories of same-subject constructions:

(1) Effort constructions

S expends energy in order to realise a situation. For example:

Vietnam would strive to achieve an early comprehensive political solution to the war in Cambodia.

Note: Matrix verbs which fall under the category of effort constructions overwhelmingly co-occur with to-infinitive forms of complementation

(2) Mental Process constructions

S considers engaging in some sort of situation. For instance:

For a wild moment she contemplated locking the door against him....

(3) Attitude constructions

S formulates an attitude towards a situation which may possibly involve him or her. For example:

I hate going to the cinema.

(4) Communication constructions

S describes, raises the question of, or expresses an attitude regarding, his or her possible participation in some sort of situation. For example:

I agreed to assist.

(5) Aspect constructions

S begins, continues or discontinues his or her participation in a particular situation. For example:

They began to ascend the staircase.

(6) Applied attitude constructions

This category contains constructions which, to a certain degree, consist of the characteristics of both Attitude constructions and of Aspect constructions. They resemble the latter insofar as they clearly indicate whether or not the complement situation was fulfilled; they resemble the former in that they always encode an attitude of some sort, either on the part of the speaker or the subject, to this same situation. For example:

Nevertheless she condescended to reply.

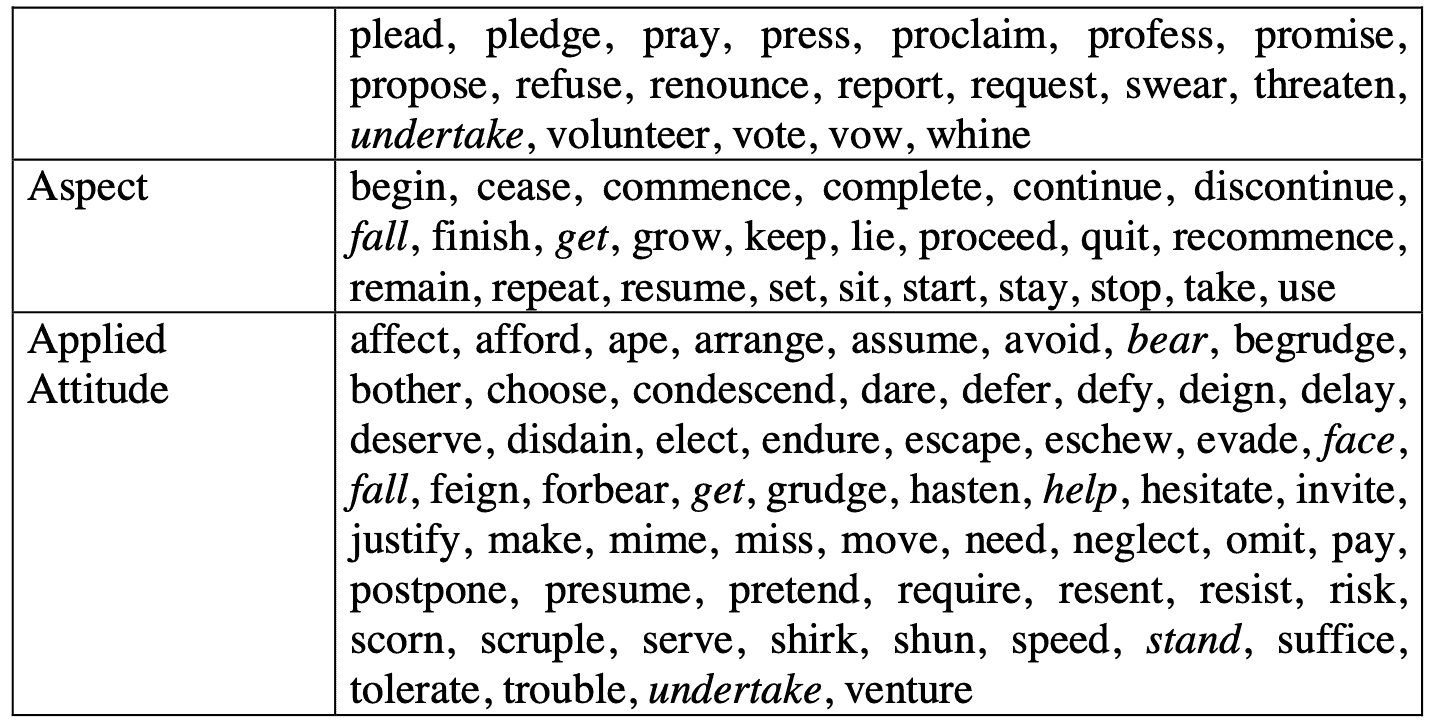

Below is a semantic classification of all the main verbs covered in Egan’s study which precede same-subject infinitive and -ing clauses (in Egan, 2008: 28-29):

* Verbs listed twice are in italics

Comparing different-subject and same-subject constructions

For both sets of constructions - different-subject and same-subject - Egan (2008: 27) points out that their constituent categories are not watertight. Some main verbs take complements in several categories. The verb feel, for example, may assume both a perceptive role and that of a mental process when it comes to different-subject clauses.

5. To-infinitives and Gerunds - Six Types of Construction on the basis of the main verb and complement situation

According to Egan (2008: 39-40), there are six types of construction which emerge from the relationship between the main verb and the complement situation. You’re already aware of the forward-looking and backward-looking constructions. However, I’ll include them again to make this classification scheme complete:

(1) Same-time constructions

With same-time constructions, a situation occurs simultaneously with the main verb. For example:

I can taste blood running down the back of my throat …

(2) Backward-looking constructions

The situation is profiled as occurring before the time of the main verb. For instance:

Adam stopped walking and stared at her.

(3) Forward-looking constructions

Here, the situation is expected to occur after the time of the main verb. For example:

He then requested Lucy and Jean to come into the kitchen.

(4) General constructions

A situation is likely to occur on a regular basis. For example:

… God’s own country, as the Canadians delight to call it.

(5) Judgement constructions

Whereby a situation is hypothesised to be true. For example:

Theodora judged her to be in her early forties …

(6) Contemplation constructions

For example:

For a wild moment she contemplated locking the door against him …

Comments

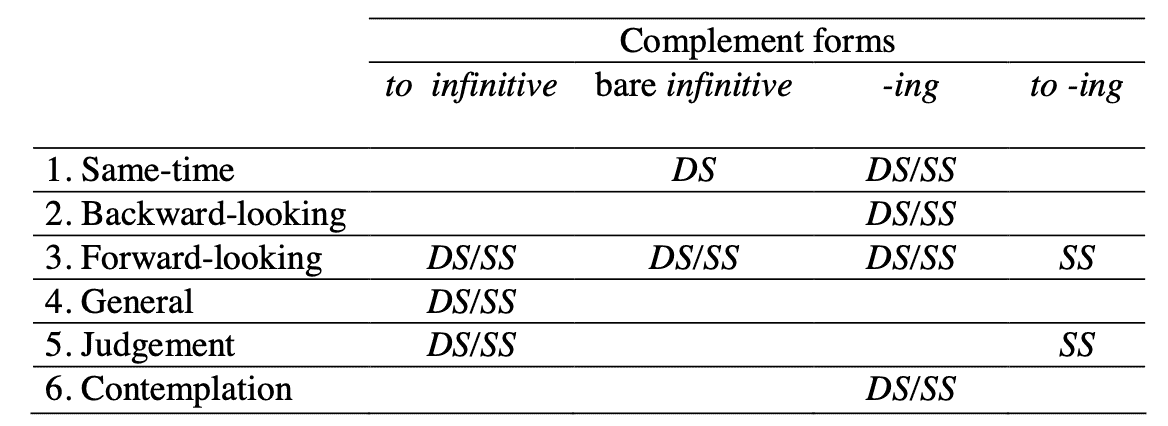

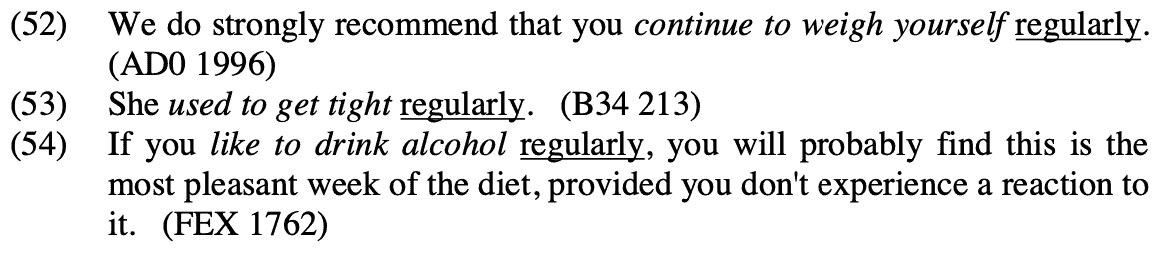

With the three aforementioned classification schemes in mind, Egan (2008: 42) neatly summarises the forms of complement which occur with various types of main verb in both DS and SS constructions in accordance with the relationship between the main verb and the complement situation:

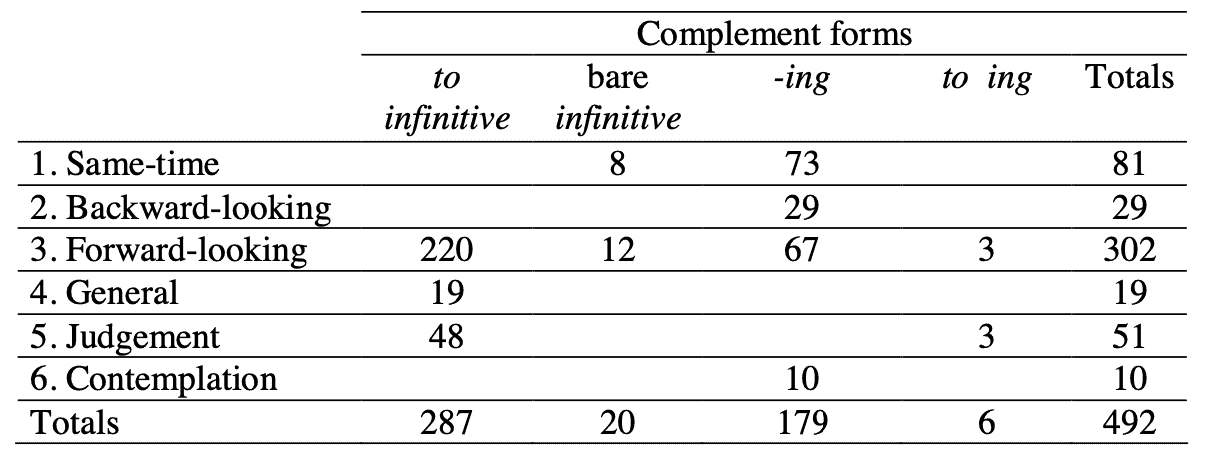

Particularly relevant to the topic of this post - choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives - Egan (2008: 43) goes one step further in his next table. Consider the number of constructions in Egan’s study based on the relationship between the main verb and the complement situation:

You may draw your own conclusions from the tables above. However, one key observation I have is that the -ing form perhaps has more forward-looking qualities than we are led to believe by certain authors of grammar guides who write about with gerunds and to-infinitives in a very superficial manner.

Matrix verbs which naturally co-occur with to-infinitives and gerunds

Now that we have established that to-infinitives are firmly associated with Forward-looking, General and Judgment constructions, I will now assess eight verbs which only, or almost always, co-occur with to-infinitives, and a further eight verbs which co-occur with gerunds.

The frequency of the various constructions is based on projected totals in the British National Corpus (BNC). Egan (2008) went to great lengths to include a large database of verbs in Appendix 1 of his book. Hence, the tables I will add below are from Egan’s book. Nevertheless, I have accessed the BNC in order to extract some example sentences which contain each verb together with a to-infinitive or gerund.

Matrix verbs + to-infinitive

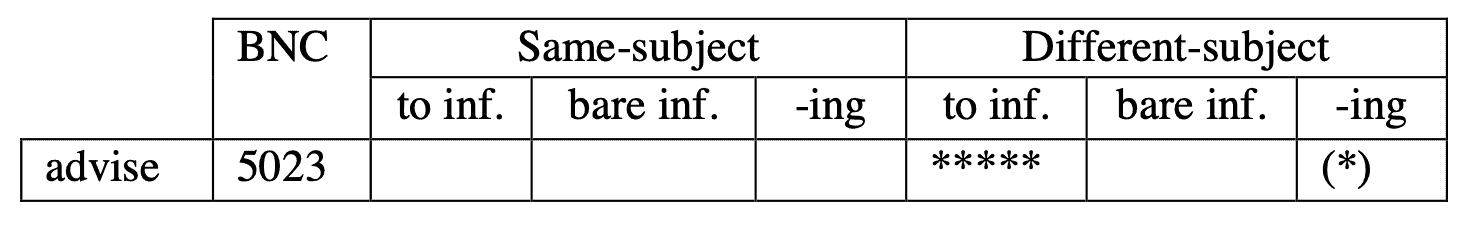

1. advise

advise occurs in Forward-looking Communications constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

I advise you to see your solicitor, she said

I would advise you to step forward at once and explain yourself

You must be careful of your reputation. I advise you to keep him at a distance until you are married

We would advise you to give us sufficient notice, usually 12 working days prior to Auction date

Their accountants advised them to put further capital into the business or sell it.

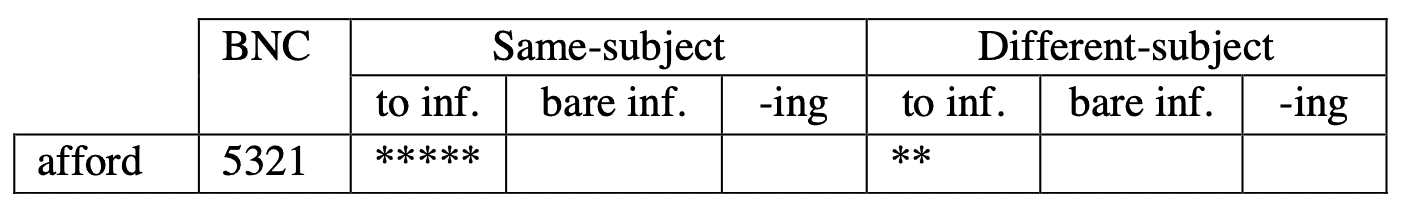

2. afford

afford occurs in Forward-Looking Applied Attitude and Enablement constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

We can not afford to let the Labour Party go on unopposed

In fact, in this present market, the question isn't can you afford to install gas central heating. It's can you afford not to?

And, thankfully, many can afford to splash out a little on treats and luxuries

You see, even the most sympathetic of employers may not be able to afford to carry on paying you

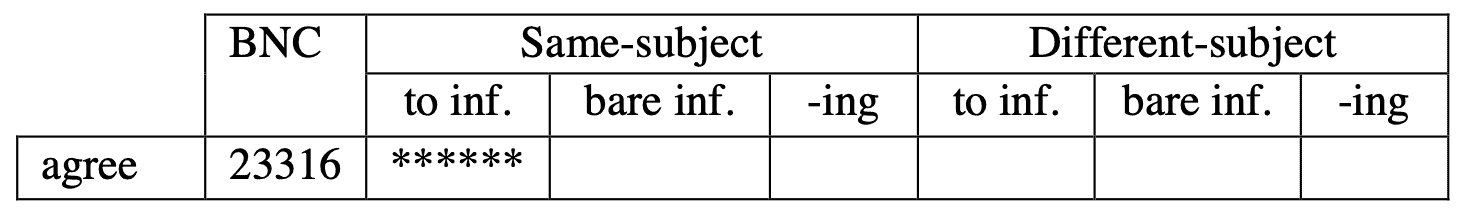

3. agree

agree occurs in a Forward-looking Communication construction.

Example sentences from the BNC:

I hope the Council will agree to ask the Town Clerk to express concern at the way it's being handled

At it's meeting last November, the Policy Committee did agree to review the overall spending limits in the light of the final revenue Support Claim

It is an 11-nation club where all the members agree to keep the value of their currencies within fixed bands

The group agree to develop more collaborative projects

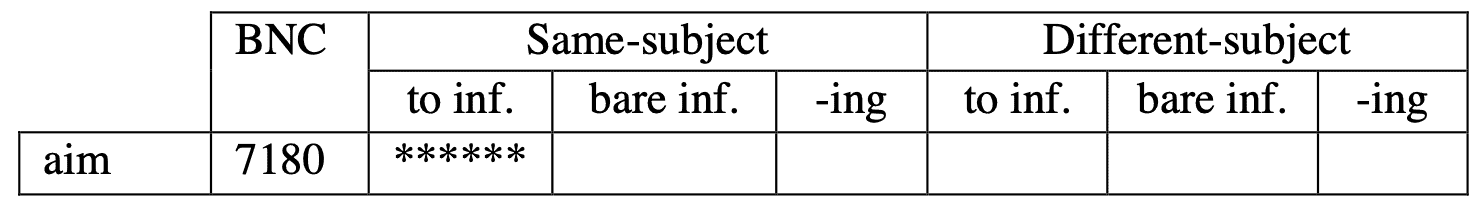

4. aim

aim occurs in a Forward-looking Effort construction.

Example sentences from the BNC:

And let's aim to have that by the end of February

I aim to prove that privacy is a thing of the past, says Dame Edna

This department will aim to encourage private sector enterprise in all these fields

We aim to remove all significant dereliction from Wales by the end of the new Parliament.

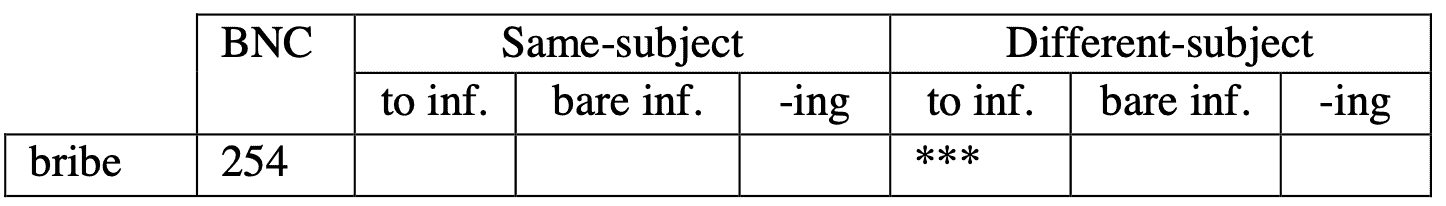

5. bribe

bribe occurs in a Forward-looking Enablement construction.

Example sentence from the BNC:

We detest you so much we will bribe you to go away.

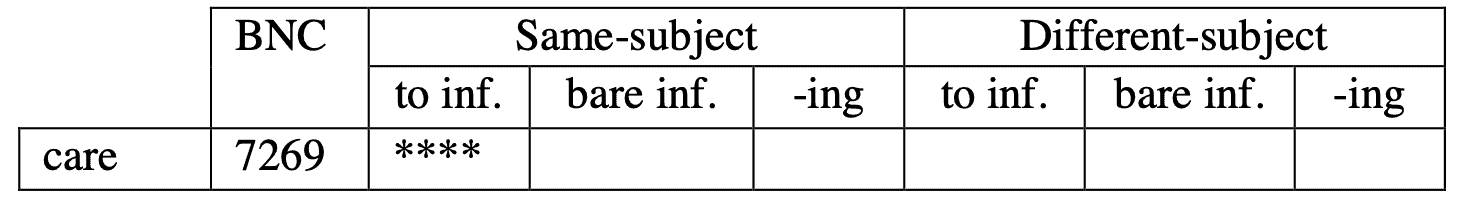

6. care

care occurs in a General Attitude construction.

Example sentences from the BNC:

Perhaps you'd care to explain, Mr Chairman, to those who don't know

if you would care to stand up to identify yourself please

There is a great deal of written evidence available on the subject for those who care to take a deeper look

I would not care to go there as a tourist in the season of pilgrims

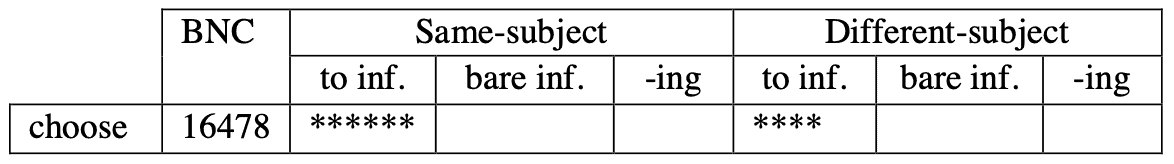

7. choose

choose occurs in Forward-looking Applied Attitude and Enablement constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

And of course we're offering a service of allowing people to choose to come at four rather than six

You can choose to fly back to either Gatwick, Birmingham, Bristol or Manchester

The environment you choose to learn in plays a crucial role in how well you progress

You may choose to set your daily caloric intake anywhere between those two limits

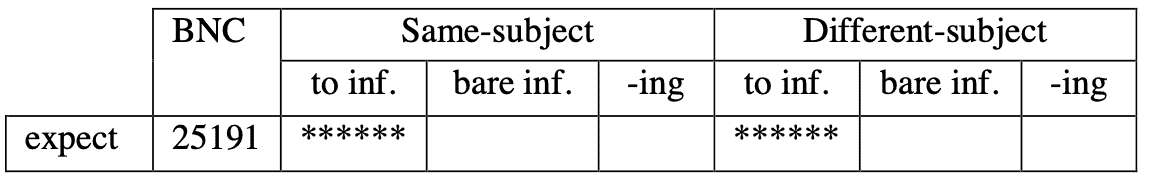

8. expect

expect occurs in two Forward-looking Mental Process constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

I half expected him to say they stole them from somebody's garden

He was so candid that, for a moment, Kelly expected him to reveal that they had had dinner together

You never expected him to come, did you?

But it isn't something they'll expect her to confide even if they know about it

You can't expect her to get them in on a student's grant

Matrix verbs + gerund

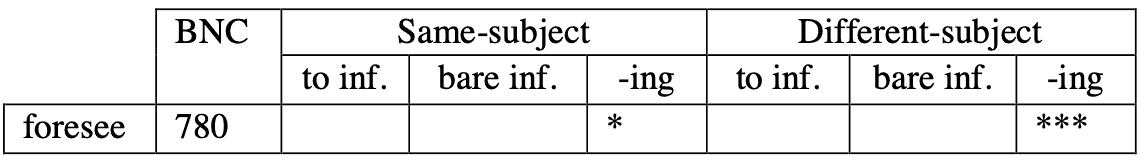

1. foresee

foresee occurs in two Forward-looking Mental Process constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

we couldn't foresee the wagon having two punctures

I didn't foresee anyone uncoupling the Lorrimores

Incidentally, I foresee a major problem looming next season

I foresee the photographic work becoming much more project oriented than it has been

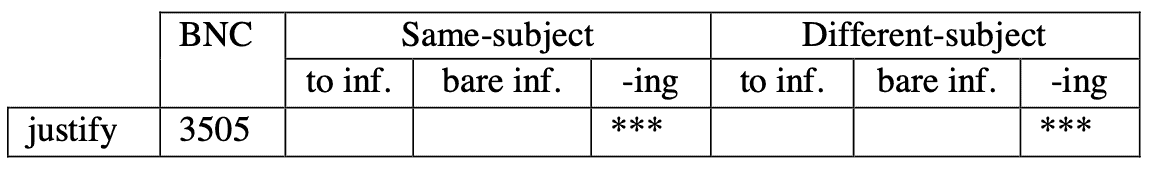

2. justify

justify occurs in Same-time Applied Attitude and Attitude constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

I mean how can you justify talking to her about that when the efficiency is improved

It could be argued that these provisions would justify allowing any person to challenge exercises of power A

I don't really think at that time I would have had enough experience to justify going on the staff

The 200 must be perceived as a refined car, if Rover is to justify charging slightly more than the going rate for its class

How can we possibly justify creating 7,000 additional children's books each year?

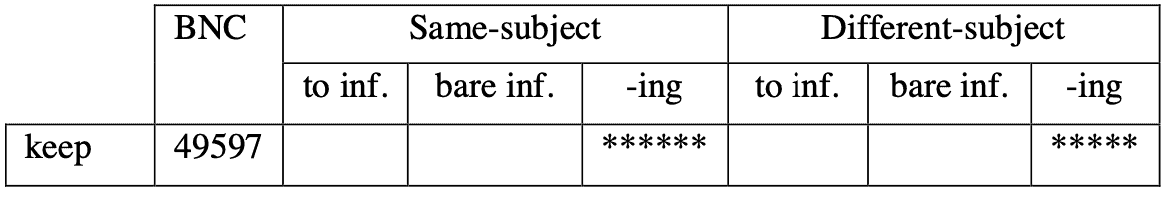

3. keep

keep occurs in Same-time Aspect and Forward-looking Causation constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

More and more evidence is piling up against Sellafield, but they keep trotting out the same old thing

And as long as drugs maintain their trendy image, youngsters will keep falling for them

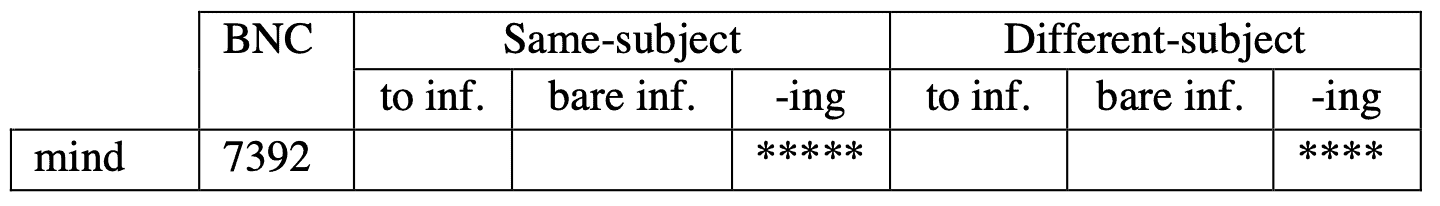

4. mind

mind occurs in two Same-time (or Forward-looking?) Attitude constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

Now if you two wouldn't mind just moving back... there... good…

But Elton probably wouldn't mind exchanging his sparkling shorts to suffer Adams' lumberjack shirts if it meant having a song at number one for 16 weeks like the Canadian rocker did

Diana, Barry's wife of 35 years, doesn't mind him meeting all the great screen goddesses

A few of them actually asked if I would mind having the clothes ripped off my back

I don't mind talking about it because it helps me get over what happened

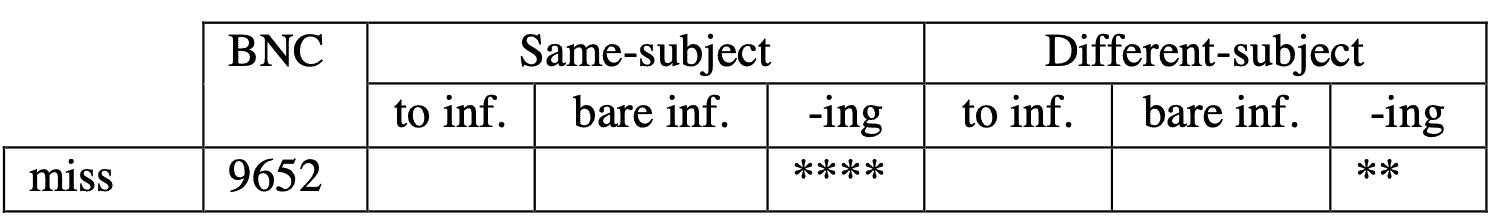

5. miss

miss occurs in Forward-looking Applied Attitude (1) and Perception (2) constructions, and a Same-time Attitude (3) construction.

Example sentences from the BNC:

But whenever I go home I hang around and I miss making music something awful

… some policemen also talk sadly of how they miss seeing their children when on nights

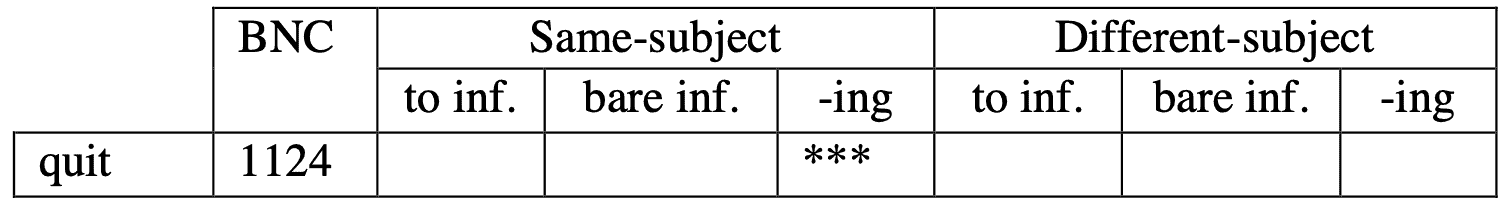

6. quit

quit occurs in a Backward-looking Aspect construction.

Example sentences from the BNC:

After that I decided to quit working on teeth and start cutting records instead

Former Jam star Paul Weller has vowed to quit dabbling in politics to boost his pop career

She has to quit living in the past

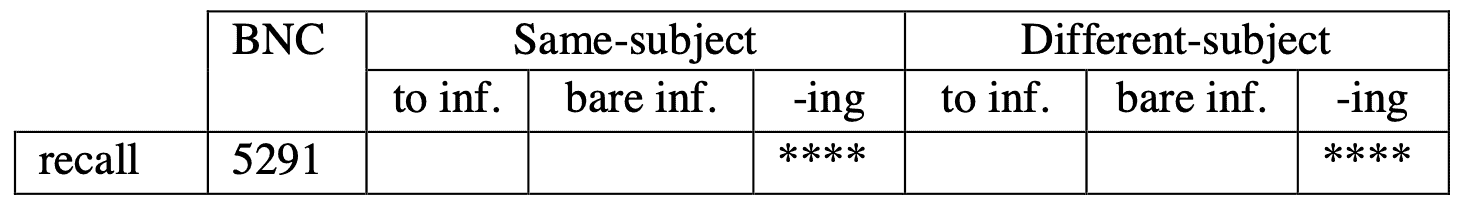

7. recall

recall occurs in two Backward-looking Mental Process constructions.

Example sentences from the BNC:

I recall seeing the lowest contribution I think was fifty pence, wasn't it?

Certainly nothing that I recall seeing as a result of the intercept ever contradicted that assessment

Experience indicates that when investors lose money they are often unable to recall being warned of the risks involved …

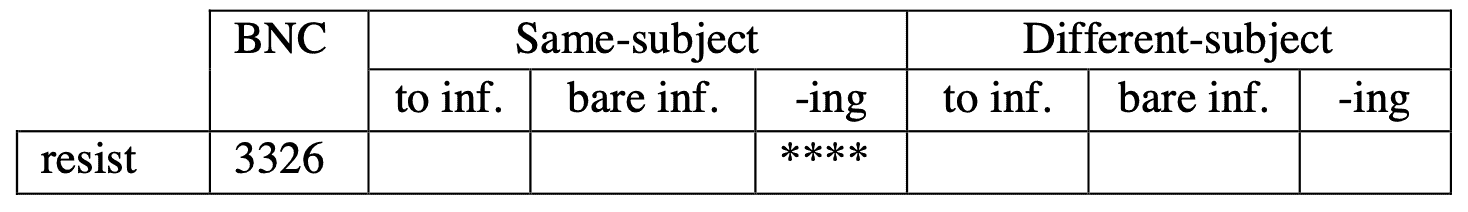

8. resist

resist occurs in a Forward-looking Applied Attitude construction.

Example sentences from the BNC:

But if you are going round the bend and resist seeking any help you are deemed to be perfectly okay

The Government could not resist adding offences under the Official Secrets Acts 1911 and 1920

… they will still resist drawing conclusions about the proximity of the mass media to state institutions …

Time Zone also normalises your skin so it can resist forming lines and wrinkles for years longer than you'd expect

Two debates connected with to-infinitives and gerunds

Choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives becomes much trickier when you consider that the to-infinitive is not always neatly tied to forward-looking constructions. Moreover, the gerund is not always synonymous with backward-looking constructions.

The aim of this section is to explore those types of matrix verbs, to-infinitive forms and gerund forms which do not fit neatly into the dichotomy of forward-looking and backward-looking constructions.

1. Should we only associate ‘futurity’ with the to-infinitive?

In his 2008 book, Egan takes several authors (such as Duffley and Bailey, 1992) to task over their perceptions that there’s always some element of futurity (in relation to the main verb) involved in the use of the to-infinitive.

Egan (2008: 62) highlights the fact that there are two other types of to-infinitive complement construction which are not forward-looking. Let’s very briefly consider them:

(a) Judgement Perception / Judgment Mental Process constructions

There’s a set of constructions that contain to-infinitive forms which have dubious connections with the notion of futurity. We shall refer to these as Judgement constructions whereby some situation is hypothesised to be true.

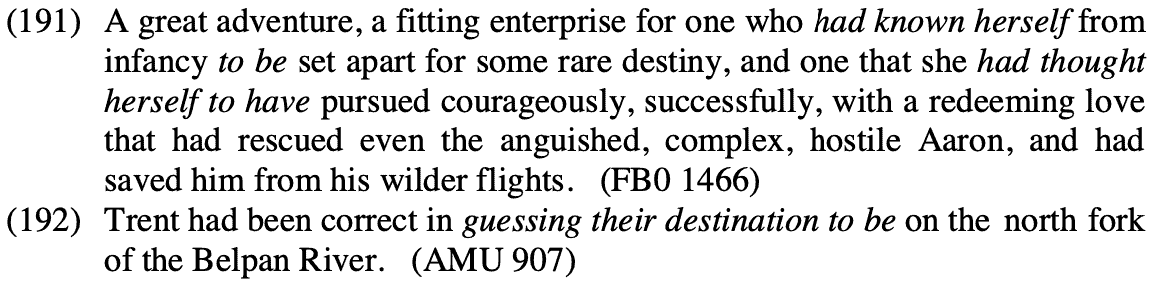

In Egan’s (2008: 98) words, Judgement to-infinitive complements revolve around “a situation, viewed as a whole, [which] is profiled as likely to be true.” Judgement constructions encode an opinion about the complement situation. This is either a firm conjecture, as with the ‘know S2 to infinitive’ (see below - 191), or a weaker one, as in the case of the ‘guess S2 to infinitive’ (see below - 192):

In Egan, 2008: 97

Here are some other illustrative examples of Judgement constructions found in Egan (2008: 94):

In Egan, 2008: 94

Egan (2008: 59) also distinguishes between two Judgement ‘‘find S2 to infinitive’ constructions. These are a Mental Process construction meaning ‘S1 judges S2 to infinitive’ and a Perception construction meaning ‘S1 discovers S2 to infinitive’. The two types of constructions are exemplified in the two sentences below, respectively:

1. I found them ... to be gross without openness, and cunning without refinement

2. The exhilaration soon faded upon checking his fuel state, which he found to be low

Overall, judgement Mental Process constructions are much more numerous than their Perception counterparts. According to Egan (2008: 63), it is more difficult to detect any trace of futurity in Mental Process constructions.

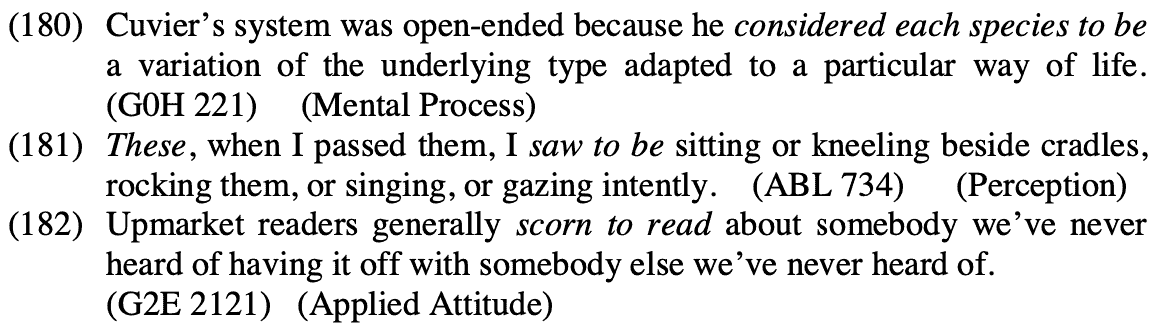

(b) General constructions

The other set of constructions which contain to-infinitive forms and also have loose connections with the notion of futurity are what Egan terms General constructions. This is when a situation is likely to occur on a more or less regular basis.

This sentence (in Egan, 2008: 47) is particularly representative of the General type of constructions:

First of all because Italians don’ t like to go abroad!

Certainly, there’s no hint of futurity in this example, as it assumes the same role as the following constructions which clearly occur at regular intervals due to the adverbial regularly:

In Egan, 2008: 35

Hence, it’s clear that General constructions “often make concrete reference to the occasions on which one can expect the situation to be realised” (Egan, 2008: 97). Typical single-word adverbials which complement these constructions are regularly and generally. However, Egan (ibid.) also highlights references which take the form of adverbials, such as when I can, every morning and when we are hungry.

As Egan (2008: 175) puts forward, there are several negative attitude matrix verbs which take to-infinitive complements and possess General rather than forward-looking characteristics. These verbs include bear and stand. Here are two example sentences offered by Egan (2008: 176):

1. ‘Even the most hard-hearted father could hardly bear to have them out of his sight for long.’

2. I can’t stand to see people being cruel to animals it absolutely appals me, it does really, I feel like to take an axe to them

2. To what extent do -ing complements occur in forward-looking constructions?

Choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives becomes even more complicated when you consider that -ing complements can also occur in Forward-looking constructions as well as their more familiar backward-looking contexts. Let’s check the number of constructions in Egan’s study once more for confirmation:

Hence, Egan focused on a total of 179 -ing complement forms in his study. As many as 77 refer to complement situations located either in the future, with regard to the matrix verb, or in the mind of the subject.

Egan picks up on the versatility of the -ing complement (2008: 109). It is versatile in terms of both the types of main verb with which it occurs, and the type of complement situation it encodes. Indeed, it may encode activities, states (being), accomplishments and achievements.

When it comes to the main topic of this post - choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives - many -ing complements with forward-looking qualities express “near reality” (Dirven 1989: 127). The verbs imply that “an activity was more or less due to occur, but was just not realized” (ibid.). Examples of such verbs include dread, delay, postpone, avoid, escape and resist. The lack of realisation connected with these types of verbs is a far cry from to-infinitives which are more associated with realisation and completion.

Egan (2008: 108-09) shares plenty of example sentences of forward-looking constructions which he located in the BNC. The main verbs in these sentences assume various roles. I will only share the matrix verbs together with the -ing complements for reasons of brevity:

a. … envisage starting … (Mental Process)

b. … dreaded him coming … (Attitude)

c. … discuss moving the trough … (Communication)

d. … forbids us releasing names … (Enablement)

e. … prevent the crimes being committed (Causation)

f. … had delayed telling anyone … (Applied Attitude)

Finally, this sentence (in Egan, 2008: 67) is an intriguing one:

I started losing my hair at twenty nine.

This example is particularly pertinent to the debate of choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives. The -ing form suggests that the activity is a progressive, or durative, ongoing one whereby the hair-loss is gradual. Indeed, one may lose a strand here, or a strand there. In most cases, the activity of hair-loss should not be viewed as a “homogeneous whole” (Egan, 2008: 67).

Summary

This post has proved that it’s no straightforward task for learners of English to retrieve correct -ing or to-infinitive forms after every matrix verb they utter.

It’s true that mistakes in choosing between to-infinitives and -ing forms seldom lead to critical misunderstandings. However, I believe this particular subject matter is not one of Grammar nonsense (to borrow part of the title of Hugh Dellar and Andrew Walkley’s book which I have also reviewed on this blog). That’s because making a poor choice between a to-infinitive and -ing form may impact on the emphasis a speaker wishes to convey with a particular utterance. If the -ing form performs an attitudinal function after verbs such as like and hate, then students of English should strive to evoke such appropriate emphasis in their utterances.

Finally, choosing between gerunds and to-infinitives becomes a lot easier when learners make the effort to explore corpora. I urge all of my students to do just that.

References

Close, R.A. (1992). A Teachers’ Grammar: The central problems of English, Hove: Heinle ELT

Dirven, R. (1989), ‘A cognitive perspective on complementation’, in: D. Jaspers, W. Klooster, Y. Putseys, and P. Seuren (eds.), Sentential complementation and the lexicon: studies in honour of Wim de Geest. Dordrecht: Foris. 113- 139.

Duffley, P.J. (2004) Verbs of Liking with the Infinitive and the Gerund, English Studies, 85:4, 358-380

Egan, T. (2008). Non-finite Complementation: A usage-based study of infinitive and -ing clauses in English, Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi

Parrott, M. (2000). Grammar for English Language Teachers, Second Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press