Using corpora in English language classes

I must admit that the issue of using corpora in English language classes has weighed on my mind for a number of years.

I’ve always been eager to build my students’ knowledge of collocations and lexical chunks. I will define these terms later.

Finally, at the beginning of 2025, I started to make use of the British National Corpus (BNC) to develop, predominantly, my students’ collocational knowledge of:

(a) previously learned words, which I recorded in their lesson notes

(b) a small selection of words in articles the students are expected to read before each class.

(c) delexical verbs

A little bit about the British National Corpus

Completed in 1994, the BNC comprises around 100 million words of text from an extensive range of genres. These include fiction, spoken, academic, newspapers and magazines.

The spoken part of the BNC (roughly 10%) consists of orthographic transcriptions of unscripted informal conversations and spoken language amassed in different contexts. These range from government meetings to radio shows.

The written part of the BNC (90%) contains, for instance, extracts from national and regional newspapers, journals, academic books and popular fiction, university essays and published and unpublished letters and memoranda.

The BNC is closely related to other corpora from English-Corpora.org, such as the Movie Corpus and Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA).

How can English language teachers exploit corpora to create exercises and activities based on collocations and lexical chunks?

From a lexical point of view, and from the perspective of spoken English, one of the general strengths of corpora is that they reveal authentic language data pertaining to English. Engaging in the study of corpora may help to dispel commonly-held assumptions which educators and native speakers in general may hold. Indeed, teachers cannot always rely on their intuition when it comes to the meaning and usage of lexical items.

Teachers can set about using corpora in English language classes in a variety of ways, as I shall explore below.

1. Focus on what is frequent in the English language rather than relying on intuition and tradition

Mauranen (2004, p.90) provides the example of the verb ‘to think’. Most of us would presume that the meaning of ‘to think’ refers to “some ponderous mental activity”. However, once you delve deeper into corpora, it becomes apparent that ‘think’ is more associated with the meaning ‘have an opinion’. Check out this example from the BNC (Davies, 2004):

Well, I don't think there's much more we can do here tonight, but before we wind things up, I think I'd like a word with that lad upstairs

With the example from the BNC above in mind, Mauranen (2004, p.92) states that:

… we can replace recommendations of language use which are solely based on tradition or teacher intuition. It has become a common finding that what is taught as functional language use is not necessarily in agreement with what is frequent in the language, or even appears at all.

2. Acquaint students with common collocations of previously met words

When it comes to defining collocations, I’m rather in agreement with Timmis (2015, p.24) who states that a collocation is a “combination of two lexical (as opposed to grammatical) words often found together or in close proximity …”

Certainly, make sense and dire straits are collocations. However, as Timmis (ibid.) points out, tutors should not view collocations as chunks which merely consist of two words. Firstly, if a pair of words is separated by an article, as in have a party, this should still count as a collocation. Secondly, phrasal verbs such as carry out may be treated as one word. Therefore, carry out an experiment still counts as a collocation.

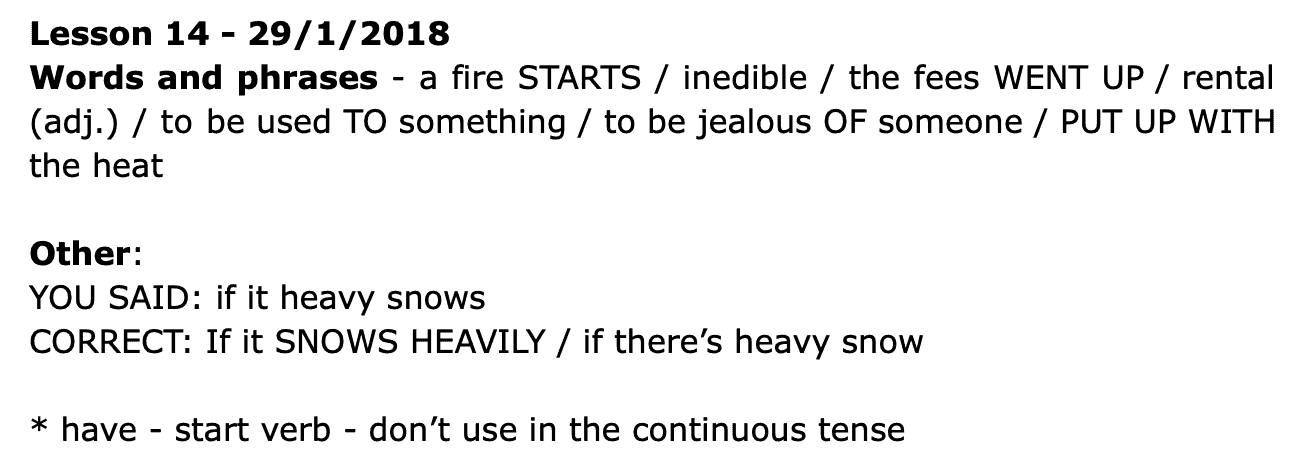

I see it as my duty as a teacher to record lesson notes for students which detail newly learned words, errors made during speaking and pronunciation errors. Since the turn of 2025, I’ve begun to revisit some of my students’ earliest entries, as you can see below with my student Maksim:

Exploiting student notes for the purpose of building collocational knowledge of previously learned words

The above set of notes is seven years old. It is unlikely that this student revisits his oldest sets of lesson notes. However, I believe that these words and collocations are somewhere in the back of his mind and can be ‘reawakened’.

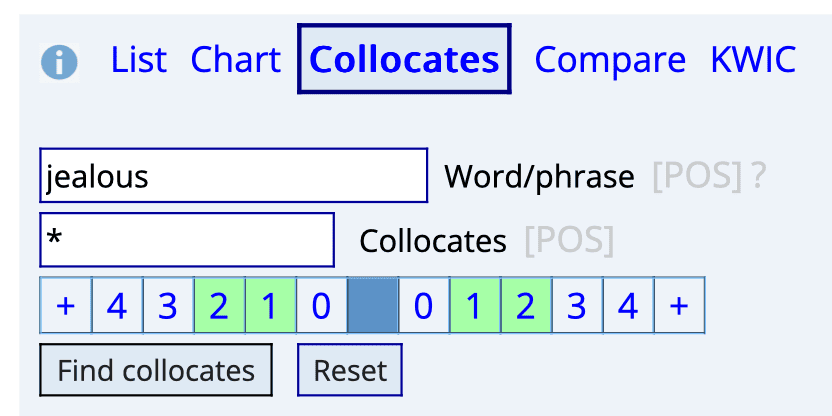

Using corpora in English language classes makes a great deal of sense when you can head to the ‘collocates’ display in the BNC and see what words commonly occur near your target word. I recently reacquainted Maxim with the word jealous, which only returns 897 results in the ‘List’. Therefore, jealous is not a frequently occurring entry in the BNC.

In the search I just carried out for the purposes of writing this post, I set the number of words occurring before and after jealous to ‘2’:

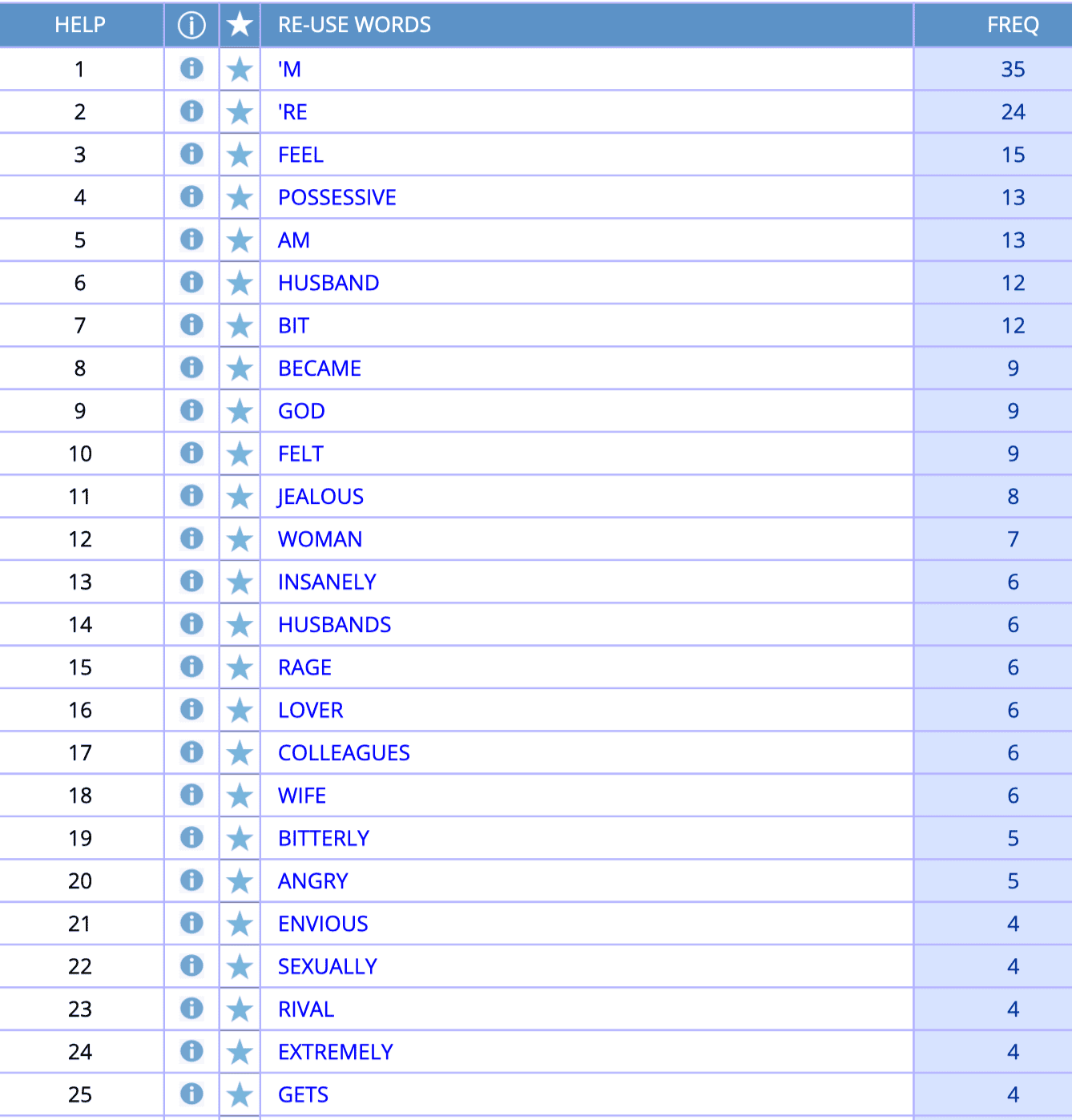

Clicking on ‘Find collocates’ reveals the following results (top 25 as a sample only):

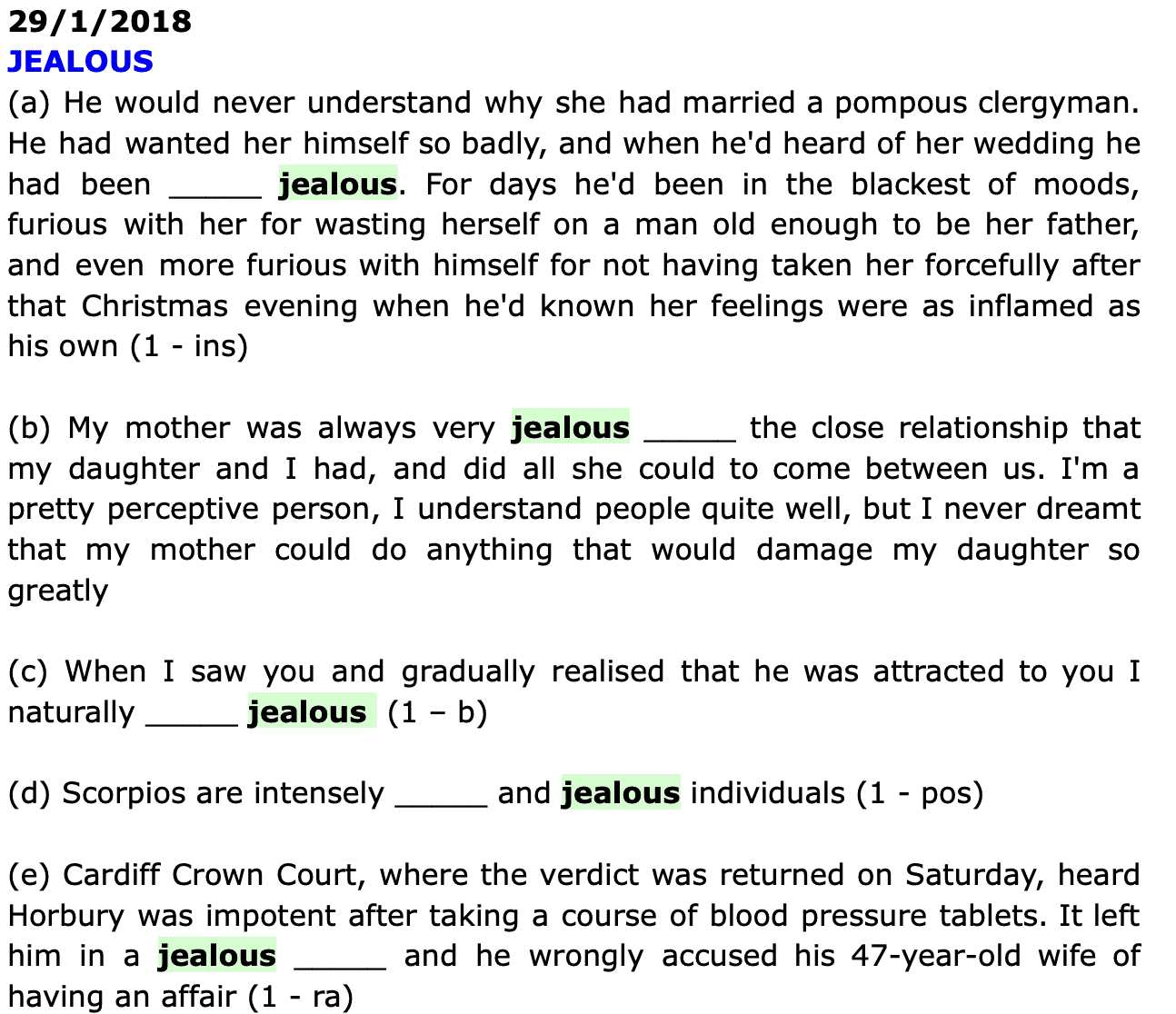

The majority of sentences I select for students tend to have rich collocational value when it comes to each target word. As you can see below, I tend to focus on collocations which consist of two words. However, I do sometimes focus on multiple-word lexical chunks and on prepositions which come after target words:

As you can see above, I provide the first letter or letters of the missing word after each sentence according to how complex and common I think the collocation is. In (c), for example, I only provided the first letter (b) because there’s a very limited range of verbs which could precede jealous here. The missing word is became. Conversely, in (d), the number of potential missing words (adjectives) beginning with the letter ‘p’ is extensive. Therefore, I provided the first three letters (pos) of the missing word (possessive).

The numbers after the sentences represent the number of words which should go into the gaps.

For your reference, here are the solutions for the sentences relating to jealous:

Wrapping up this section, I’m still in two minds as to whether to inform students of the target word, or words, in advance of each class. The upside of this idea is that my students are generally keen to consult the BNC and note down or print off the most common collocations of a target word before each class. Conversely, I sometimes get the impression that those who are prepared with their list of collocations don’t read through the sentences I provide as they’re too eager to provide the right answers. Therefore, they may miss out on developing crucial deductive skills.

The Rationalization of Collocations

Writing about the ‘Rationalization of Collocations’, Tsui (2004, p.54) shares one of the queries a teacher had on TeleNex - a website for English language teachers in Hong Kong. This teacher asked whether one can say ‘well-experienced’:

If we say someone is experienced, we mean this person has certain knowledge or expertise. Do we have ‘well-experienced’ as well? If so, does it mean there is an even higher level of expertise?

Tsui then goes on to quote a native speaker of English who was a member of staff from TELEC (Teachers of English Language Education Centre) in the Department of Curriculum and Educational Studies at the University of Hong Kong. This lecturer was a bit unsure about ‘well-experienced’ so looked it up in the corpus:

There weren’t any examples of well-experienced at all. To express an even higher level of expertise, the examples from the corpus showed that people use adverbs such as very and vastly - but these don’t seem to be very common … Mind you, … , even if there is such a word as well-experienced, I’m now not so sure that it means more than experienced. Similarly, is a well-educated person more educated than an educated one?

Tsui subsequently conducted a search on the MEC in TeleCorpora on the word experienced. It showed that there are 105 instances of experienced in adjective form. However, there are only 25 cases where experienced was modified by intensifiers such as ‘very’ and by comparatives and superlatives like ‘more’ and ‘most’. A quick search on the BNC just now yielded only eight instances of ‘well experienced’.

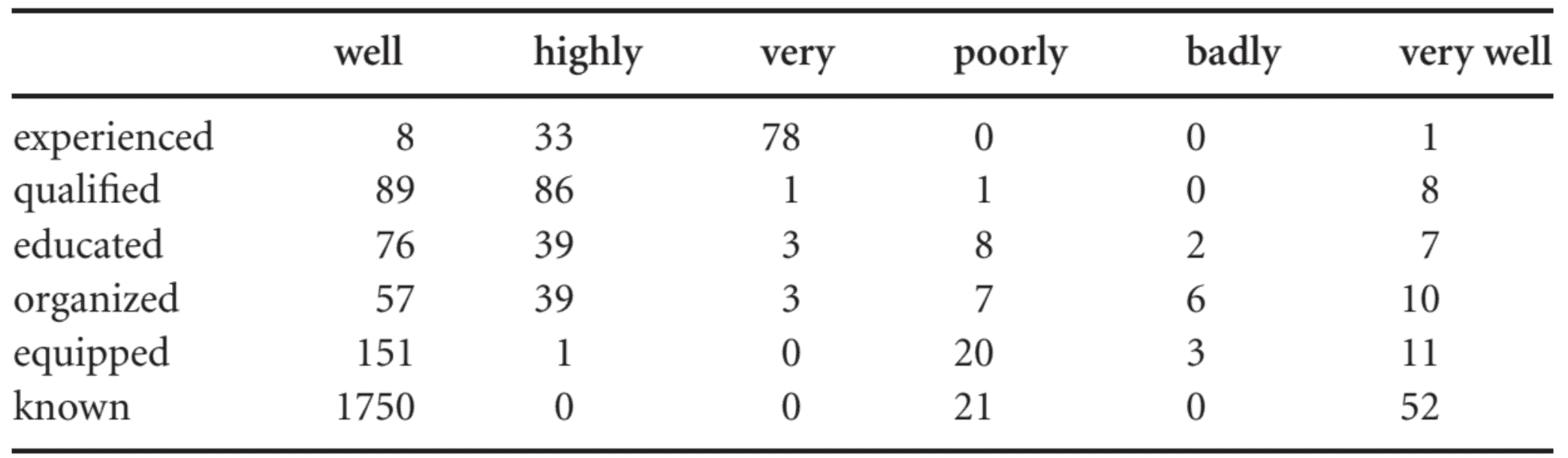

Tsui carried out a search in the BNC to investigate any difference in the behavior between experienced and other adjectives which take ‘well’ as the modifier. The search yielded the following compound adjectives: ‘well qualified’, ‘well educated’, ‘well organised’, ‘well equipped’ and ‘well-known’. In order to find out whether the rare occurrence of ‘well experienced’ is connected with the semantics of ‘experienced’, Tsui conducted another search on the following modifying adverbs: ‘highly’, ‘very’, ‘poorly’ and ‘badly’. Here are the results of the search (Tsui, 2004, p.56):

As a result of the search, Tsui offers the following observations:

1. The occurrence of ‘well experienced’ is significantly fewer than the other modifier + adjective combinations;

2. Although there is a large number of instances of ‘experienced’ taking the intensifier ‘very’, there are very few or no instances of the other five adjectives following ‘very’;

3. The five adjectives, except ‘experienced’, take the intensifier ‘very’ when they combine with ‘well’ to form compound adjectives;

4. Even though the adverbs ‘poorly’ and ‘badly’ can modify ‘educated’, ‘organised’, ‘equipped’ and ‘known’, ‘experienced’ does not collocate with the said adverbs.

According to Tsui (2004, p.56), the four observations above suggest that “it is likely that experienced denotes a positive quality which renders the modification by ‘well’ superfluous and the contradictory modification by ‘poorly’ and ‘badly’ unacceptable.” By contrast, as Tsui (ibid.) continues, “except for ‘qualified’, the other adjectives can be modified by adverbs denoting negative qualities, suggesting that they can be used neutrally, though they commonly denote positive qualities.”

3. Build students’ knowledge of formulaic expressions / lexical chunks

A lexical chunk, also known as a formulaic expression, formulaic sequence and a prefabricated chunk, is “a frequent meaningful sequence of words that may include both lexical and grammatical words”. (Timmis, p.26). For example, ‘to a certain degree’ includes a preposition and an article.

As Lindstromberg and Boers (2008, p.8) note, lexical chunks are “diverse in type”. Such chunks may indeed be strong collocations. However, there are other forms and types which assume various functions (ibid.):

- Conversational fillers - you know what I mean, sort of

- Pragmatic notices - excuse me, How are you doing?

- Discourse organisers - The thing is, Having said that

- Sentence heads - Could you …?, Why not …?

- Phrasal verbs - break down, put off

- Compounds - credit card, weather forecast

- Figurative idioms - make ends meet, break the ice

Teachers keen on using corpora in English language classes should be encouraged by the opportunities afforded by lexical chunks when it comes to developing linguistically valuable and highly motivating awareness-raising exercises and activities. For example, teachers can get students to identify likely chunks in texts or extracts of authentic speech. The next step could be for students to use online corpora, such as the BNC, to check the relative frequency of chunks/word sequences.

4. Help students to know delexical verbs inside out

‘Delexical’ verbs, also known as ‘light’ verbs, depend on the nouns which accompany them for their meaning. Examples of delexical verbs include have, make, do, get, give and take.

Light verb constructions include a noun and may also include a preposition:

I didn’t take advantage of the opportunity

Are you giving a presentation at the seminar next week?

David made such a terrible mistake

In the examples above, I have underlined the light verbs. The words in bold comprise the delexical verb constructions. To reiterate what I hinted at in the opening sentence to this section, the main meaning in light verb constructions resides with the noun. The light verb itself contributes very little content to an utterance.

I’ve written about the various meanings of get before here on this blog. In my view, fluency revolves around having quick access to a wide variety of lexical chunks, particularly chunks and collocations dominated by lexical verbs such as get.

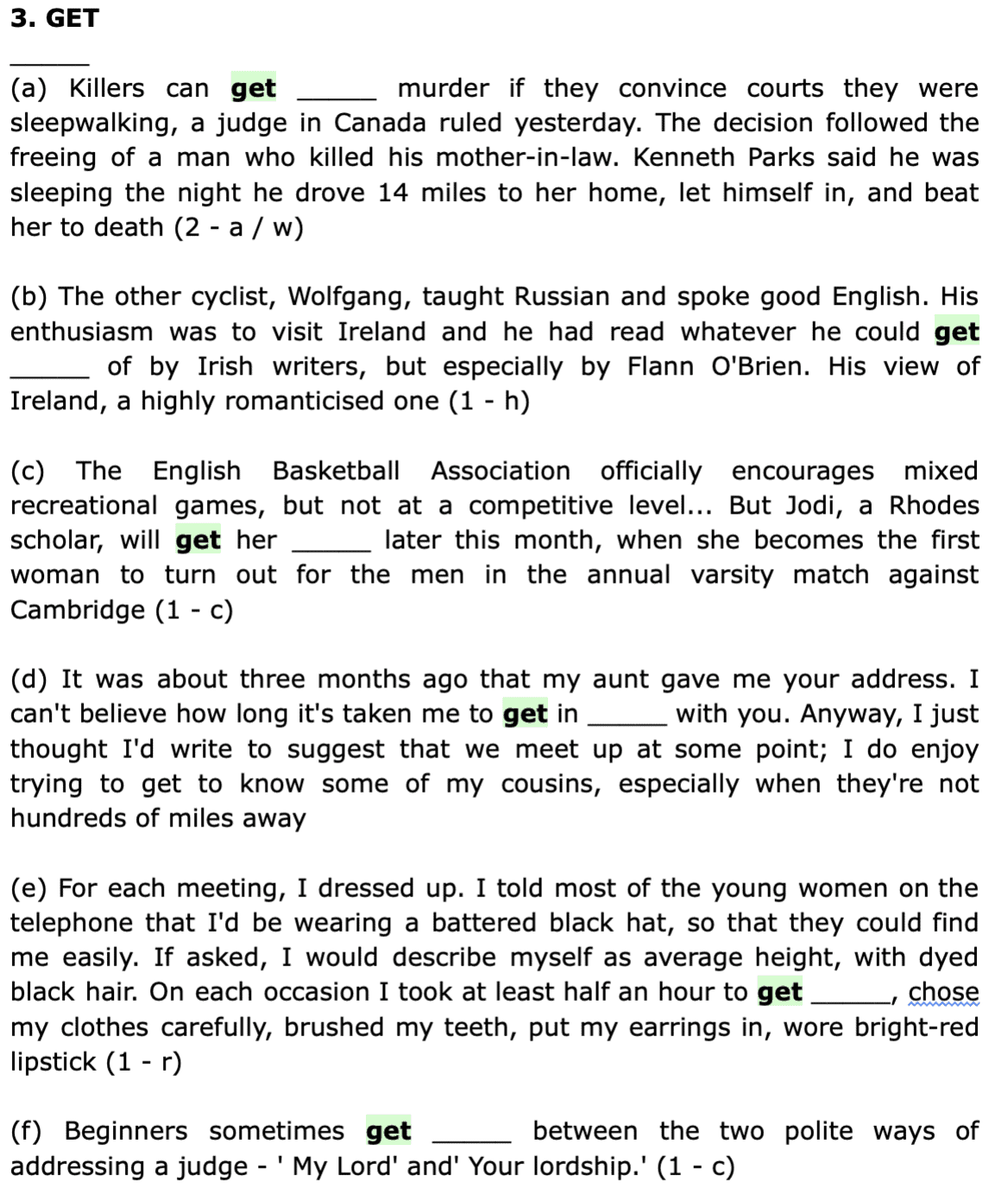

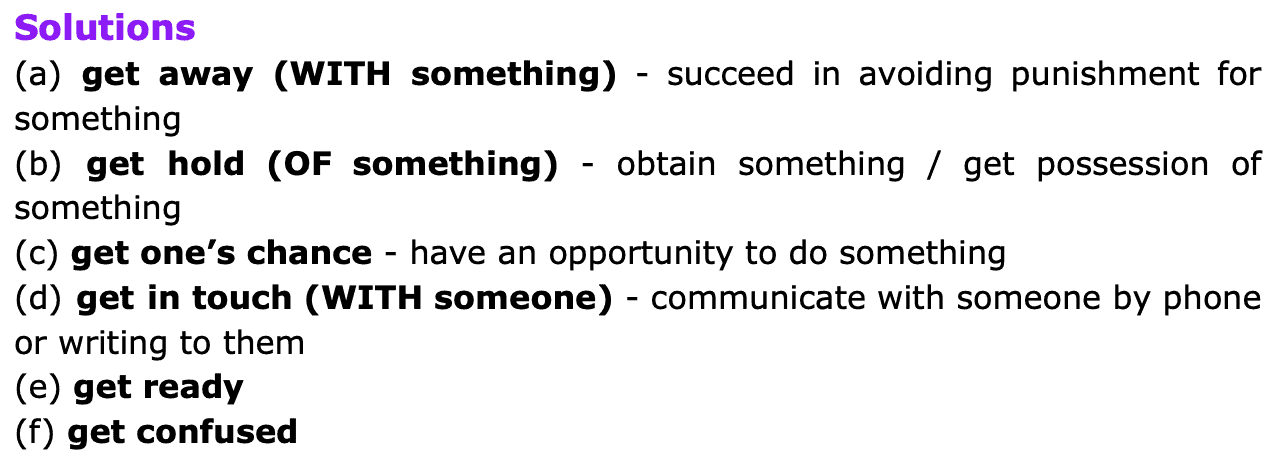

In recent times, I’ve set about testing my students’ knowledge of collocations and lexical chunks containing the delexical verb ‘get’:

I believe that the majority of my students have come across these chunks and collocations countless times before. However, due to irregular exposure and a lack of willingness to notice and underline these chunks and collocations while reading, these pieces of language are very much dormant in my students’ mental lexical chunk dictionaries.

5. Synonymous lexical items

Finally, I recommend using corpora in English language classes to compare synonymous lexical items. Tsui (2004, p.44) assesses the differences in meaning and usage between the adjectives tall and high.

In many languages, there may be no difference at all between very similar words in English. Indeed, Tsui (2004, p.45) points out that the difference in usage between tall and high is problematic for Chinese learners of English to grasp as there is no such distinction in Chinese. It’s a similar situation in Polish whereby the word wysoki functions as both tall and high.

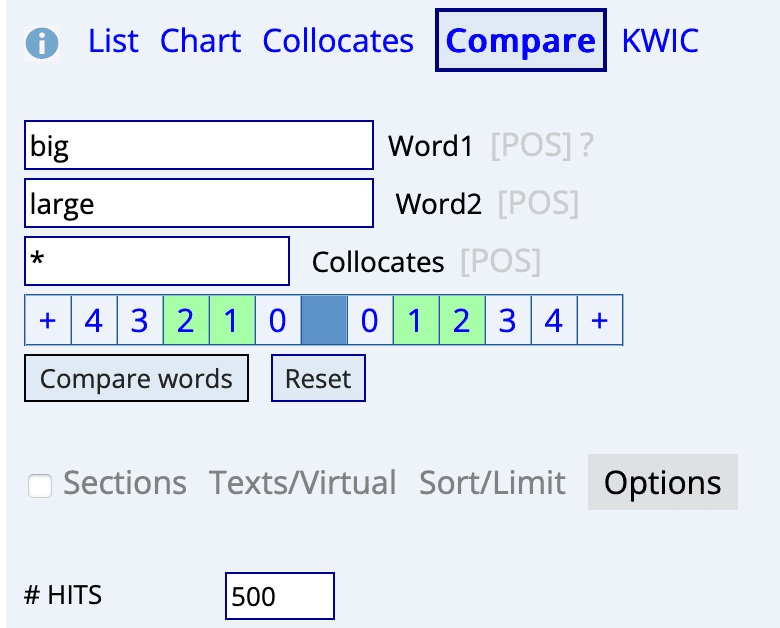

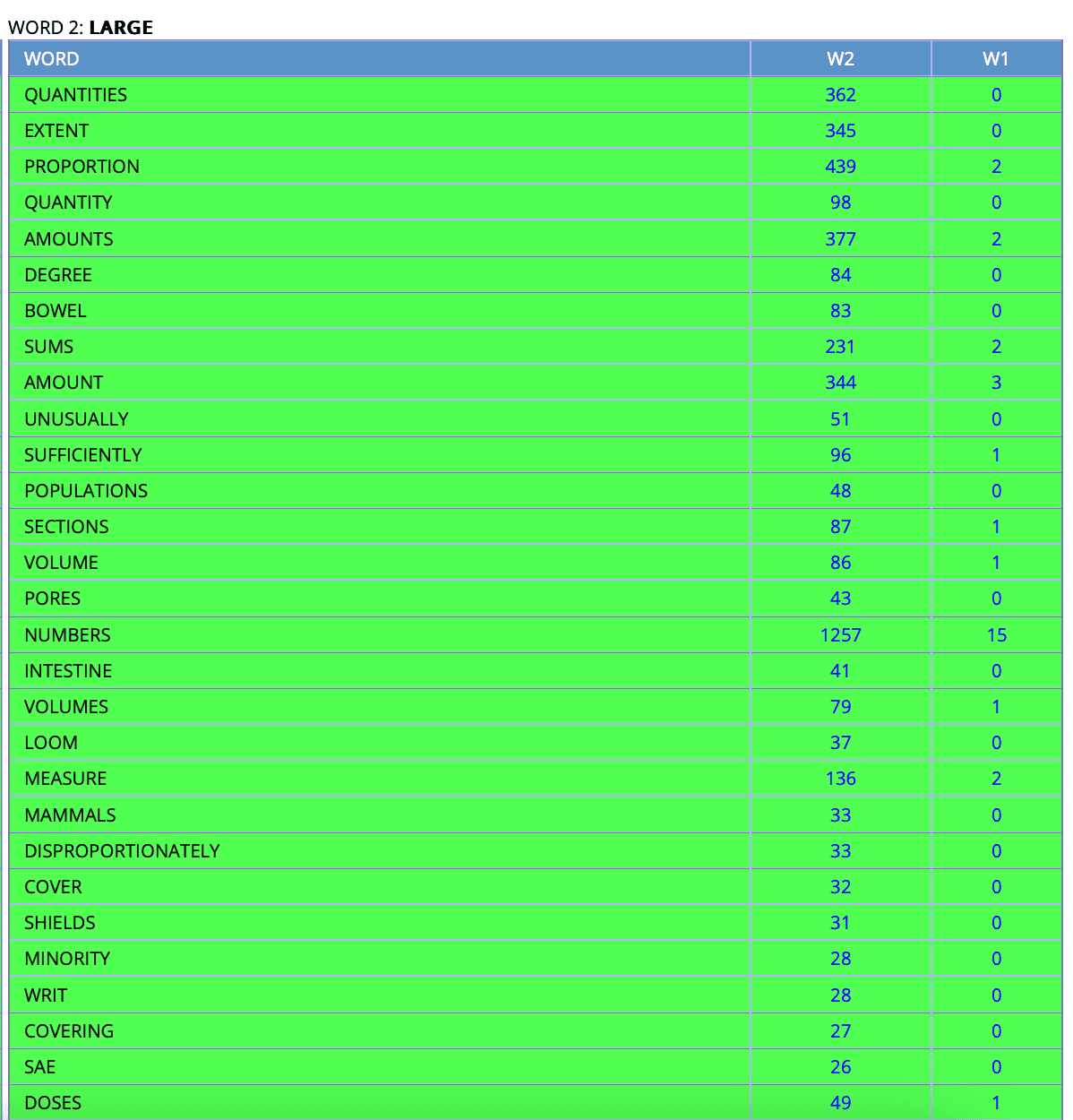

Now we can go to the Compare words display in the BNC to compare the collocates of two words in order to see how they differ in meaning and usage. For example, let’s compare big and large:

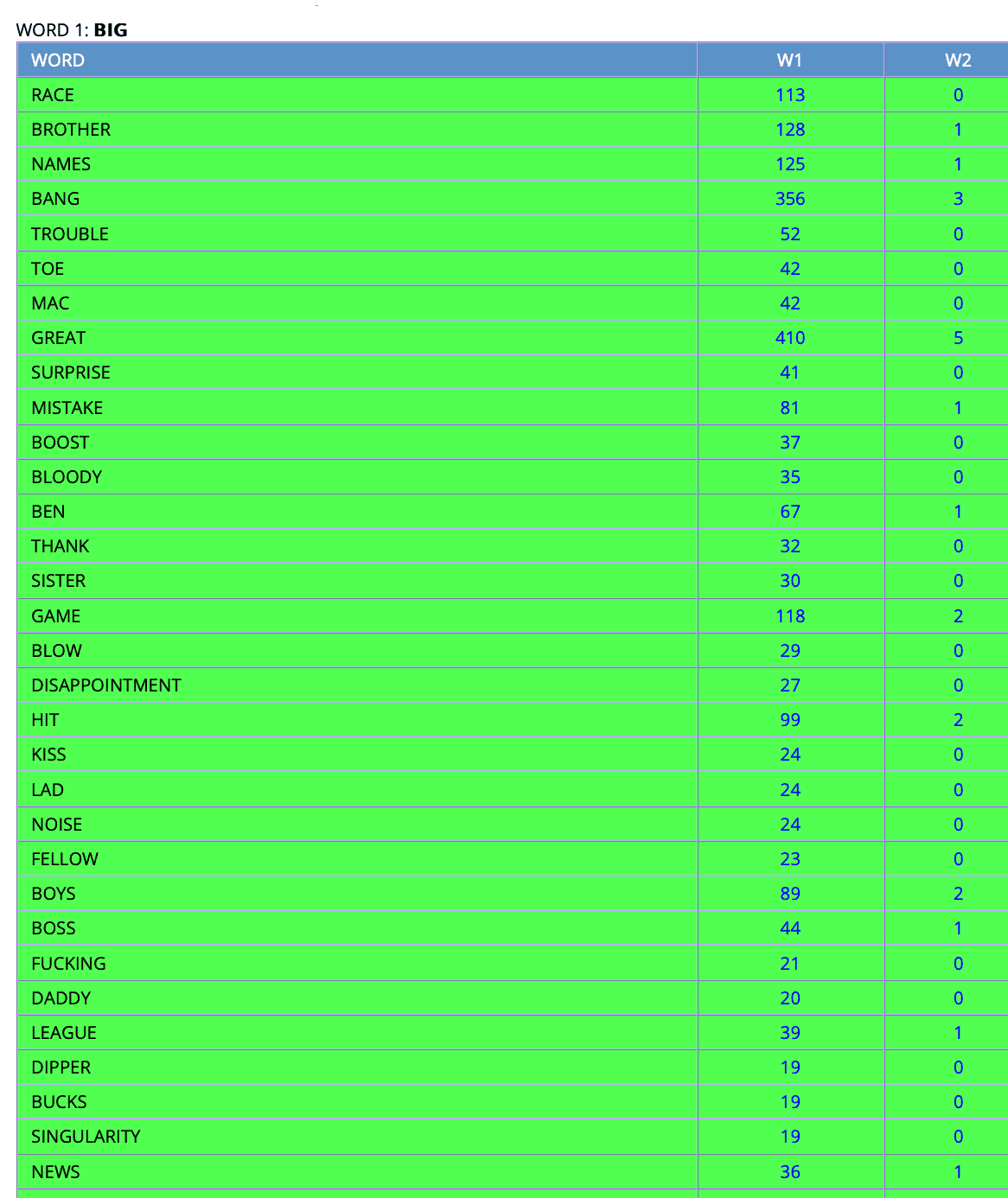

It’s worth showing lists such as the ones below with students to discuss observations regarding usage:

What immediately jumps out to me is the way in which large is used with quantity words - quantities, proportion and amounts. Conversely, big tends to appear in informal fixed expressions - big blow, big trouble, big news.

Overall, you can put groups of intermediate to advanced students into pairs. By using the Compare words display in the BNC, ask each pair to do some study and come to conclusions regarding synonymous lexical items. Other synonymous lexical items include:

- small - little

- low - short

- occasion - chance

- quiet - silent

Final Thoughts

Overall, this post has made it abundantly clear that using corpora in English language classes should be an absolute necessity. Certainly, syllabus writers with a more lexical view of language learning need to consult corpora more than they do rather than rely on native-speaker intuition and introspection. The use of corpora should be another weapon in the fight to help students overcome the intermediate plateau and become advanced speakers of English.

References:

Davies, M. (2004) British National Corpus (from Oxford University Press). Available online at https://www.english-corpora.org/bnc/

Lindstromberg, S., and Boers, F. (2008). Teaching Chunks of Language: From noticing to remembering, Helbling Languages

Mauranen, A. (2004) ‘Spoken corpus for an ordinary learner’, in Sinclair, J.McH (ed.) How to use Corpora in Language Teaching, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp.89-105

Timmis, I. (2015). Corpus Linguistics for ELT: Research and Practice, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge

Tsui, A.B.M. (2004) ‘What teachers have always wanted to know’, in Sinclair, J.McH (ed.) How to use Corpora in Language Teaching, Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp.39-61