Dialects in the UK: In recognition of the many distinct varieties

How many distinct dialects in the UK are there?

Well, the number 40 is bandied about in many articles on the Internet. However, we need to be careful with this number and sweeping generalisations such as “there’s pretty much one accent per county”, as put forward in this post. In fact, there are very many dialects within dialects in the UK. This is particularly true in the country I grew up in - Northamptonshire.

Before we get down to the nitty-gritty of some of the defining features of dialects in the United Kingdom, and my passion for dialect and accent preservation, let’s briefly consider what is meant by the terms accent and dialect.

What is the difference between an accent and a dialect?

The term accent concerns the way that a certain group of people pronounces words and phrases.

A prominent variation in pronunciation in England is the so-called ‘BATH vowel’. In essence, the quality of the ‘a’ vowel sound differs between northern and southern accents. For instance, someone from Oxford, in the south of England, would typically pronounce ‘bath’ with the long ‘a’ (/bɑːθ/). Conversely, someone from Leeds, in the north, would commonly pronounce ‘bath’ with the short ‘a’ of ‘hat’.

Dialect is a reasonable term to use when referring to the role of vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation. One of the most distinctive dialects in the UK is that of Newcastle upon Tyne and the surrounding areas. This dialect is known as the ‘Geordie’ dialect. The Geordie dialect has an intriguingly rich vocabulary. For example, Geordies might say ‘gan’ instead of ‘go’, ‘haway’ rather than ‘come on!’ and ‘lass’ instead of ‘girl’.

Overall, then, accent is just a contributing factor among a person’s or group’s broader dialect. There is a phenomenally high level of accent diversity in the UK.

The origins of accents and dialects in the UK

The 1500 or so years in which English has been spoken on the British Isles has enabled the language to evolve into richly distinct regional varieties of English.

In stark contrast to the situation in Britain, English has only been in use in Australia for around 230 years. Hence, dialects haven’t been able to develop to the same extent there as they have in the UK.

The Angles, Saxons and Jutes

Undoubtedly, invasions and migration stimulated the development of dialects in the UK. In the fifth century, Germanic tribes hailing from the northwest of mainland Europe began to settle in England. These tribes comprised three different peoples: the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes. On the whole, the Angles settled in the central and northern parts of England, the Saxons south of the Thames (West Saxon area) and the Jutes in the region of present-day Kent.

As the Angles and Saxons were the largest groups, the settlers were given the name Anglo-Saxons. These groups arrived with their distinct dialects of their native Germanic language, the language we now refer to as Old English.

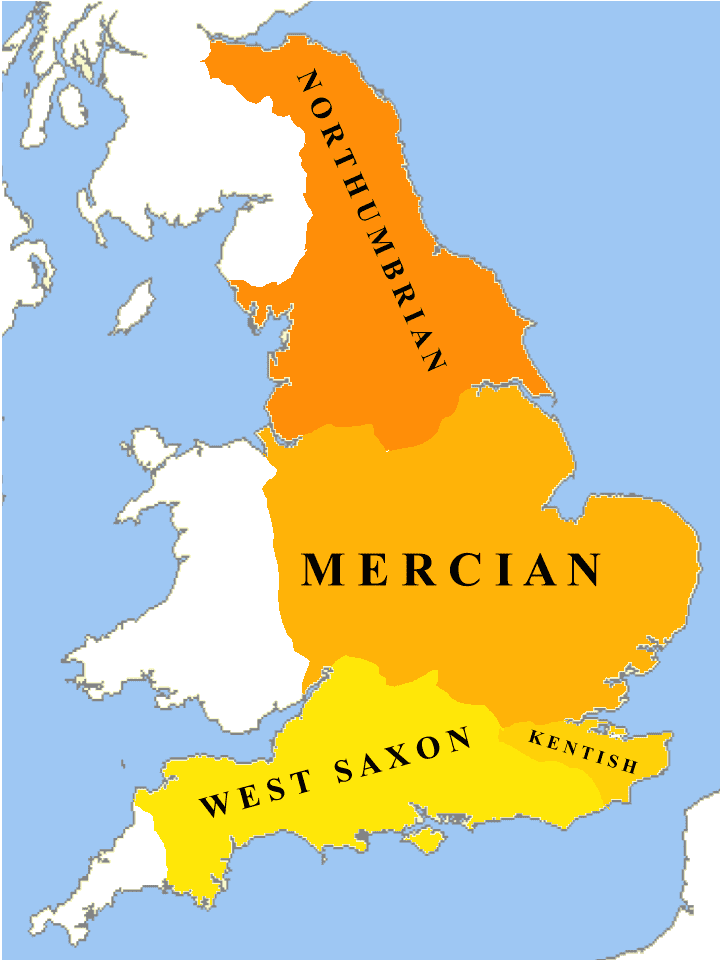

Hence, during the Old English period, England was broadly divided into four dialect areas up until around 800 AD. This was when the Vikings arrived in Britain. The four main dialectal forms of Old English were:

- Northumbrian - in northern England and southeastern Scotland

- Mercian - in central England

- West Saxon - south and southwest of the Thames

- the Kentish region - southeast of the Thames

The four main dialectal forms of Old English CelticBrain, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Viking incursions

Between 865–9, the Vikings (seafaring people from Scandinavia) conquered the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia.

Nevertheless, the Vikings faced stiff resistance throughout the 870s in the form of an army led by Alfred the Great. Alfred was the King of the West Saxons from 871 to c. 886. The most decisive battle was the Battle of Edington in 878. It was a crushing defeat for the Vikings, and it led to a peace agreement which divided up the kingdoms. The Vikings eventually settled in Northumbria and East Anglia, in a territory called the Danelaw. In this area, Old English and Old Norse (the North Germanic language of medieval Norway, Iceland, Denmark, and Sweden up to the 14th century) merged, eventually forming the essential character of later English.

Danelaw Viking territory (in red) Source: Hel-hama, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

How did Old Norse combine with Old English?

As Hough and Corbett (2007, p.11) point out, Old English and Old Norse were closely related in that they both depended on the endings of words - i.e. inflections - to indicate grammatical information. Hence, with speakers of Old Norse and Old English striving to communicate with each other, these inflections became blurred and eventually disappeared.

The nature of the English language began to change. With inflections dying out, the Anglo Saxons and speakers of Old Norse had to use different resources to express the grammatical information that the inflections had once signalled. Therefore, it was the order of words, and the meanings of function words, such as prepositions like to and over, which became prominent.

The Norman invasion and the emergence of Middle English

In 1066, the Normans - Vikings who had previously settled in France - arrived in England. They over-ran the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

By the time the Normans came to England, they were speaking a fusion of Old Norse and French i.e. Norman French. The language of the English government soon became Norman French, while English became the speech of the peasants.

Anyway, what I’m now referring to is Middle English. This was spoken after the Norman conquest right up until the late 15th century.

On the impact of French on the English language, Baker (2016: 45) noted that French was sufficiently established in England by the mid-thirteenth century:

As the primary language of the aristocratic portion of society and the law, French had a trickle-down effect on common speech, gradually becoming more attractive to commoners.

With the prevalence of French, and its desirability among Englishmen, the number of French words and units of language which made their way into English speech and the language’s lexicon proliferated. Moreover, combinations of existing French and English words formed entirely new words.

The need to respect history

Doing the research for the potted history of the origins of accents and dialects I wrote in the previous section ignited my passion for British accent and dialect study and preservation.

With all the evidence suggesting that the English spoken in Britain is becoming ever more standardised, and accents are undergoing changes never witnessed before, we need to respect the history that’s gone before us.

Of course, I could have continued above with a thorough account of how Modern English came into being. However, I would like to get to the topic at hand: Are accents and dialects in the UK dying out?

Are accents and dialects in England dying out or simply changing?

To get a sense of how dialects in the UK are undergoing changes or even dying out, I’ve delved into a number of articles from national newspapers and local newspapers up and down the country. Let me share what’s going on in two areas of England - Yorkshire and Leicester.

Dialect levelling in Yorkshire

First of all, I’ve just come across a fascinating interview with published linguist and Yorkshire dialect expert Dr Barrie Rhodes (as part of the BBC Voices series).

Essentially, Rhodes takes the line that “all language is dialect” - even the so-called Standard English dialect. Interestingly, Rhodes doesn’t like to use the term “die out”, with reference to dialects. Instead, dialects “only change”.

A large part of Yorkshire is rural and isolated. Moreover, as Rhodes revealed, Yorkshire people are known for being ferociously proud of their region and particular forms of regional language. Therefore, according to Rhodes, Yorkshire people are keener to retain dialects than those in other parts of the country.

Nevertheless, Rhodes admits that Yorkshire is “undergoing a process of levelling out.” Dialect levelling is a linguistic phenomenon by which differences between dialects decrease. It generally occurs due to large-scale mobility and linguistic and cultural mixing.

Hence, due to this levelling out, Rhodes admits that it’s getting more difficult to pinpoint the exact village someone’s from according to how they speak.

The Leicester accent is experiencing changes

Famous for its culturally diverse scene, the English city of Leicester is in the East Midlands region in central England.

Leicester is only around 35 miles northwest of my hometown, Wellingborough. Yet, pure Wellingborough and Leicester accents are markedly different.

As Marlow and Smith pointed out in a fabulous article in the Leicester Mercury, the Leicester accent is a “hotchpotch of all sorts of influences: north, north west, north east, Staffs, the south …”

The Leicester accent is a baffling one indeed. It’s like north vs south traded punches at one time or another - with the north coming out on top by a whisker.

Associate Tutor in Applied Linguistics & TESOL at The University of Leicester, Diane Davies, has investigated dialect and accent in the East Midlands. Davies confirmed in the Leicester Mercury that the accent and dialect was far more “pronounced” in the speech of older people than in teenagers.

The city of Leicester itself is changing. 61 per cent of the city’s residents were White British in 2001. This figure is closer to 45 per cent these days. This influx of Asian and African-Caribbean people to Leicester has dramatically altered the way the city sounds.

Dialects in the UK: Sound recordings and personal oral histories

With all the history that’s gone before us, and the changes British accents and dialects are currently undergoing, I’ve been thrilled to discover that the British Library and BBC joined forces to digitally store selected voice recordings of people from various parts of the UK. Let me share what I’ve discovered:

Millennium Memory Bank

The 396 Recordings in the Millennium Memory Bank section of the British Library Sound Archive can be played by anyone.

Just a little bit about the project. Throughout 1998 and 1999, forty BBC local radio stations recorded personal oral histories from a broad cross-section of society. The age of the participants ranged from five to 107. From the get-go, the project aimed to focus on local, everyday experiences whereby interviewees were encouraged to speak about events and change at a community level as opposed to developments on a national and global scale.

For me, accents from the project which caught my attention include:

1. Carlton, Barnsley - My grandmother was from Barnsley. The Barnsley accent is reputed to be one of the broadest Yorkshire accents there is. In the recording, Joe describes the basic diet he had as a child.

2. Nottingham - I studied in Nottingham for four years. The accent and dialect of Nottingham is certainly unique. It’s a Midlands accent, but I still think it has a strong whiff of the north about it with the short vowel sounds etc. For more information on the Nottingham accent and East Midlands English, check out this interview with Natalie Braber, Professor in Linguistics at Nottingham Trent University.

Survey of English dialects

Another fascinating section of the British Library Sound Archive is the Survey of English Dialects (SED).

Carried out by researchers based at the University of Leeds, the SED was an innovative survey of the vernacular speech of England. From 1950 to 1961, a team of fieldworkers collected data in a network of 313 localities across the country. The informants were predominantly male farm labourers over the age of 65. This is because the aim of the survey was to capture the most conservative forms of folk-speech. The majority of the sites visited by the researchers were rural locations because they believed that traditional dialect was best preserved in isolated areas.

I’m particularly captivated by a Mr Bill Willace from Northamptonshire (no longer available online).

Born in 1884, Bill was a retired farm worker at the time of the recording in 1957. He describes how during one particularly severe winter, the baker had to walk along the hedges to deliver his bread. Bill then proceeds to talk about the ploughing technique.

The speaker sounds very similar to my grandfather, who’s 90 years old and from Finedon, a small town just 4.5 miles east of Little Harrowden.

One phonological feature in the recording which stands out is “h-dropping”. This is a form of elision distinguished by the omission of the initial /h/ sound in words such as happy and hotel. In the recording, Bill drops the /h/ at the beginning of Hardwick [a:dIk] and really draws out the long ‘a’ sound. Hardwick is a small village, south-west of Little Harrowden.

Even though this recording of Mr Wallace is no longer available, check out this example of a Northamptonshire dialect speech. Mr Billy Williamson, from Warmington in north Northamptonshire, recalls working with carthorses and reflects on the days when farms employed large numbers of labourers.

We must respect the many British accents and dialects there are

I’ve come across a number of research studies and surveys carried out in the UK which point towards a slow fading of regional accents across England.

Check out this report which confirms that more people speak with accents similar to those in London or south-east England than they did in the 1950s.

I accept that increased mobility over the last 60 years has led to the ‘levelling’ of English accents. People have become exposed to a much wider range of accents.

However, I find it all rather sad. There are so many northern accents and dialects - Liverpool, Newcastle, Manchester and so on - which are too unique and recognisable to fade away.

Just a final thought. I once wrote a piece about students who contact me with a burning desire to sound like a “British person”. In reality, they want to sound like someone from the Royal Family. I’d much rather sound like a Geordie (Newcastle) or Scouser (Liverpool). Geordies and scousers are true characters.

References:

Baker, Curt (Spring 2016) "The Effects of the Norman Conquest on the English Language," Tenor of Our Times, Vol. 5, Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor/vol5/iss1/5

Hough, C., and Corbett, J., 2007. Beginning Old English, Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK