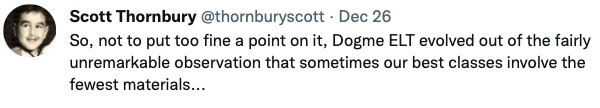

Dogme ELT – Do ELT teachers’ best classes involve the fewest materials?

The inspiration for this post about Dogme ELT (English language teaching) was a tweet I saw by ELT author and teacher trainer, Scott Thornbury:

Let’s dive in to find out what Dogme ELT is all about and the origins of the Dogme ELT ‘movement’. I’ll also provide some commentary on my own personal feelings about Dogme.

What is Dogme ELT?

Dogme ELT is considered to be both a methodology and teaching movement whose proponents challenge a perceived over-reliance on materials, coursebooks and the grammatical syllabus. The Dogme approach emphasises conversational communication in the classroom.

Origins: The relationship between Dogme ELT and a group of Danish filmmakers

Dogme 95 was a filmmaking movement set up in 1995 by Danish directors Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier.

These filmmakers sought to challenge what they viewed as cinema’s dependency on technical wizardry, special effects and fantasy. Instead, they wanted filmmakers to focus on the actual story and its significance to the audience.

Back in 2000, Thornbury went to see a Dogme film. It was a pure coincidence. At that time, Thornbury and his colleagues in Spain were becoming increasingly frustrated with the predominant grammar-heavy orthodoxy in second language teaching, as Thornbury expressed in his co-authored book Teaching Unplugged: Dogme in English Language Teaching (Thornbury and Meddings, 2009: 3):

"[the prevailing orthodoxy was] one in which the people in the room were somehow incidental to the process of teaching, where the learners were simply frogmarched down a one-way grammar street, or where the lesson space was filled to overflowing with activities, at the expense of the learning opportunities."

Thornbury subsequently read the Danish filmmakers’ manifesto - Dogme 95. He came across a metaphor for the type of teaching that he and his colleagues were striving to implement in the classroom.

The first ‘vow’ of a Dogme film-maker is:

Shooting should be done on location. Props and sets must not be brought in (if a particular prop is necessary for the story, a location must be chosen where the prop is to be found). (in Thornbury and Meddings, 2009: 3).

The Dogme 95 manifesto prompted Thornbury to write an article affirming that ELT required a similar ‘rescue action’.

The rest is history.

From Dogme 95 to A Dogma for EFL

So, Dogme ELT has its roots in Thornbury’s 2000 article - A Dogma for EFL.

Apart from references to Dogme 95 and the Danish film-makers, Thornbury picked a bone with the sheer quantity of materials teachers would often rock up to class with.

Technology has moved on. However, I believe the essence of Thornbury’s gripes still ring true of many ELT classrooms today (Thornbury, 2000: 2):

"the quantity … of coursebooks in print … an embarrassment of complementary riches in the form of videos, CD-ROMs, photocopiable resource packs, pull-out word lists, and even web-sites, not to mention the standard workbook, teacher’s book and classroom and home study cassettes."

Thornbury went on to mention “the vast battery of supplementary materials available”, as well as authentic material easily downloadable from the Internet.

Let’s not forget self-study grammar books, dictionaries, concordancing software packages and personal vocabulary organisers.

Thornbury was clearly going off on one. I’ve never seen any software packages or personal vocabulary organisers in an EFL classroom. However, few teachers could fail to Thornbury’s highly pertinent response to all this materials overload:

"Where is the inner life of the student in all this?"

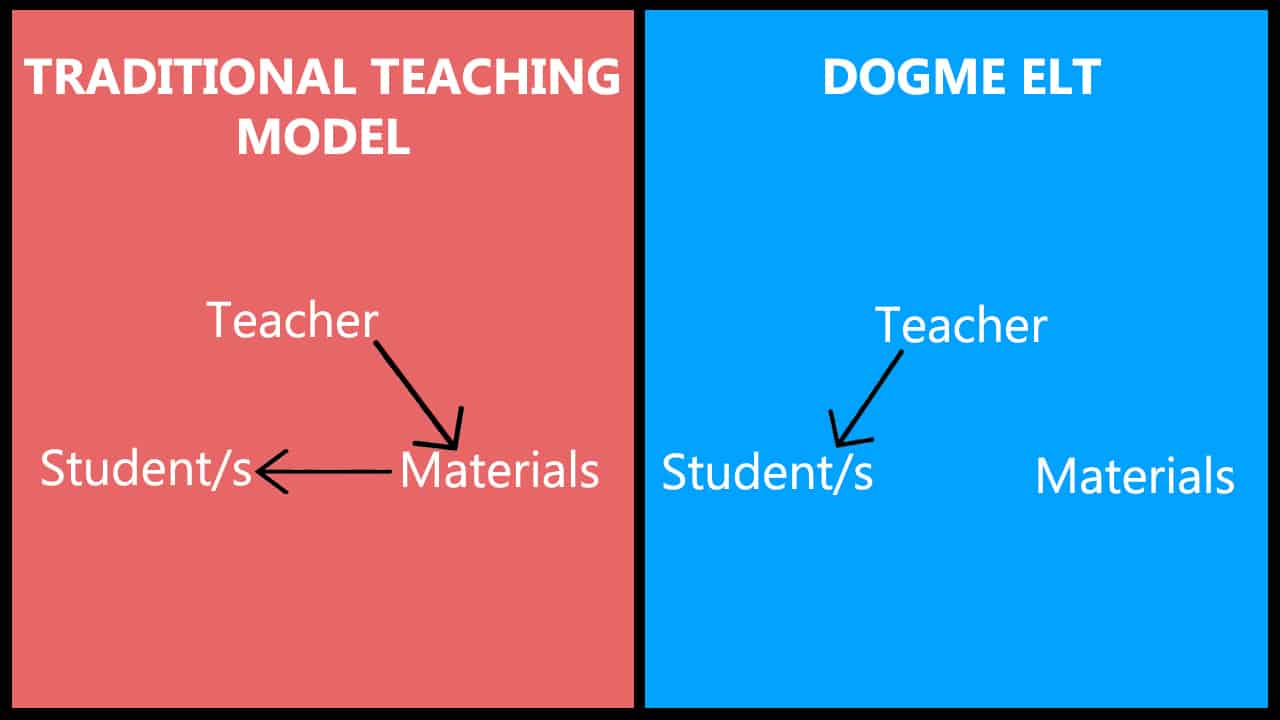

This shift away from traditional materials-heavy teaching towards teacher-student interaction can be summarised thus:

Teaching and learning should take place in the here-and-now

The main takeaway from Thornbury’s 2000 article, which the author in fact referred to as the “first commandment” in Teaching Unplugged (2009), reads:

"Teaching should be done using only the resources that teachers and students bring to the classroom - i.e. themselves - and whatever happens to be in the classroom."

Forget the “remote world of coursebook characters” and the “contrived world of grammatical structures”. Thornbury was more eager to address the “relevant concerns of the people in the room” and foster the “free flow of participant-driven input, output and feedback”.

Thornbury’s vision was of a learning environment which takes place in the here-and-now. An environment where methodologies and rules are not allowed to distort spontaneous conversation.

Ten key principles which characterise a Dogme approach

Since its inception in March 2000, Thornbury and Meddings rallied ELT professionals to contribute to debate, as well as to challenge and adapt ideas and beliefs inherent in Dogme.

Out of this ‘long conversation’, ten key principles materialised which represent a Dogme approach. Here are those ten principles, each tagged to a keyword (in Thornbury and Meddings, 2009: 7-8):

- The direct route to learning lies in the interactivity between teachers and learners, and between the learners themselves. Materials-mediated teaching is the ‘scenic’ route to learning.

- In order to engage learners and to trigger learning processes, content should be supplied by ‘people in the room’.

- Learning is a social and dialogic process, where knowledge is co-constructed rather than ‘transmitted’ from teacher/coursebook to learner.

- Learning can result from talk, especially talk that’s shaped and supported (i.e. scaffolded) by the teacher.

- Language (including grammar) emerges as opposed to being acquired. Emergent language tends to come up unpredictably. This is in contrast to the structural syllabus whereby the ‘grammar structure of the day’ reigns supreme.

- Apart from promoting the kind of classroom dynamic which is conducive to a dialogic and emergent pedagogy, the teacher should strive to optimise language learning affordances. In a nutshell, affordances are learning opportunities that arise during the lesson. They tend to arise from communication and are thus unpredictable. Directing attention to features of emergent language would be one example of an affordance.

- The learner’s beliefs, knowledge, experiences, concerns and dreams are valid content in the language classroom. This relates to the need to provide space for the learner to express their genuine voice.

- Freeing the classroom from third-party, imported materials empowers both teachers and learners.

- Texts, when used, should have relevance for the learner.

- Teachers and learners need to unpack the ideological baggage associated with English Language Teaching materials - to become critical users of such texts.

Three Core Precepts Which Emerge From the Ten Key Principles of Dogme ELT

Of these ten principles, three core precepts stand out for Thornbury and Meddings.

Let me critically assess these three precepts based on my fifteen years’ experience in ELT:

1. Dogme ELT is conversation-driven

For Thornbury and Meddings, conversation occupies a crucial role in language learning.

Conversation is language at work

Based on my experience doing good old turn-the-page coursebook-teaching in private language schools between 2006-2011, I can attest to the authors’ assertion that conversation is conventionally viewed as the product of learning. Learners first have to master the grammar and vocabulary in coursebooks before applying this knowledge in fluency activities. Hence, conversation is often the last link in the chain.

Interestingly, Thornbury and Meddings (2009) point out that Dogme shares many of the characteristics of task-based learning. In a task-based approach, the teaching-learning cycle begins with a fluency activity. Subsequent language-focused work revolves around the learner’s production. Hence, a ‘fluency-first’ approach lies at the heart of both task-based learning and Dogme ELT.

Conversation is interactive, dialogic and communicative

The communicative approach, as I experienced it working in language schools, tends to revolve around communicative interaction.

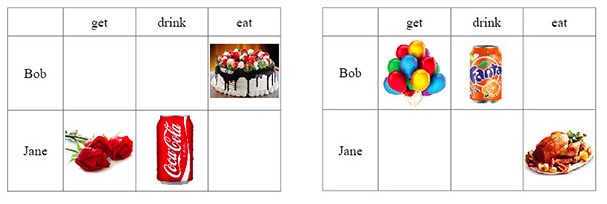

Teachers get students to do information gap activities, blindly thinking that students participate in meaningful conversation. The aim of such activities is mere information exchange - to simply get missing information from another learner. Hence, there’s a great deal of communicative interaction going on. However, this isn’t to say that speakers actually register what their co-speaker/s are saying because it’s all about catching the missing information to fill in gaps.

Michael Swan (1985: 84) highlighted the flaws of such interactive activities. Essentially, getting students to exchange “unmotivating, imposed information”, particularly about the behaviour of fictional characters in coursebooks, overlooks the more “seriously under-exploited” form of personal communication whereby students simply talk about themselves.

Look at the activity I found on the Internet below. There is a task for each partner to ask questions and answer using the Past Simple tense.

Need I say more about the artificial and non-personal nature of it all?

A core tenet of Dogme ELT is that when learners are communicating, this communication should take the form of personalised conversation. As Thornbury and Meddings (2009: 10) point out:

"This is why conversation is promoted over mere communication, since conversation is the most common and the most appropriate vehicle for the exchange of interpersonal meanings."

Frankly, I’ve done my utmost in recent years to avoid doing contrived and artificial activities with students. Conversations with my students tend to revolve around them talking about themselves in reaction to authentic reading and listening materials, such as TED talks. However, that’s not to say that I should limit teacher talking time as much as I probably do. That’s a story for another day.

2. Dogme ELT is materials-light

Ever since its inception, Dogme has carried the reputation of being a movement with one main aim - to banish coursebooks from the classroom. This doing-away-with also applies to any other materials and technological aids that teachers now take for granted.

In response to this, Thornbury and Meddings (2009) wrote that this reputation is “not entirely unfounded”.

Anti-texts?

In his 2000 article, Thornbury called for the return to a pre-method ‘state-of-grace’. Imagine the uncluttered classroom - a room with a few chairs, a blackboard, a teacher and some learners. The conversation that evolves triggers the learning process.

When linguist Geoff Jordan accused Thornbury of being very much into “fence-sitting”, it rather confirmed my own suspicions of Thornbury’s eminently watered-down and uncontroversial views. As Geoff wrote in his post:

"He [Thornbury] knows perfectly well that the bosses of the British Council, the publishing houses, the exam bodies, the training outfits and so on will simply not allow any serious attacks on current ELT practice to be made."

What gets me is this line in Thornbury’s and Meddings 2009 book:

"But it is worth emphasising at this point that a Dogme approach is not anti-materials nor anti-technology per se."

Hence, nine years after Thornbury’s surprisingly hot-headed rant, Dogme suddenly rejected the kinds of materials that don’t conform with the ten principles outlined earlier in this post. Essentially, materials would be those that “support the establishment of a local discourse community.” (Thornbury and Meddings, 2009: 12).

In my eyes, such a dramatic shift regarding the main facets of Dogme ELT signifies “fence-sitting”.

When there’s “fence-sitting” involved, how on earth can you call something a methodology, let alone a movement?

Isn’t Dogme what all ELT teachers do to a certain extent anyway?

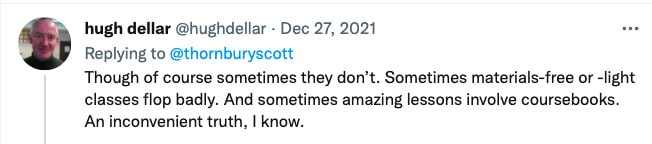

In response to Thornbury’s tweet (in the introduction of this post), author and teacher Hugh Dellar replied thus:

Hugh made an obvious, but very important, point.

Isn’t it vital to mix and match methodologies in order to keep students on their toes?

Sometimes, amazing lessons do involve coursebooks. Some coursebooks - like those Mr Dellar wrote or co-authored himself - contain a wealth of material which prompt students to engage in personalised conversation.

Let’s not sniff at the useful lexico-grammatical input some coursebook writers offer as well.

Pretexts

I agree with Thornbury and Meddings that the good intentions of coursebook writers to include discussion and personalisation tasks are usually undermined by the transparent agenda of most ELT materials - to teach grammar.

Not just any old grammar - ‘grammar McNuggets’, as Thornbury so famously proposed. In other words, the delivery and consumption of pre-selected grammatical items, such as the past perfect, regardless of whether they have any relevance to students' lives or not.

Subtexts

Coursebooks consist of subtexts.

In other words, coursebooks promote educational and cultural values which aren’t related to the needs of the learner. For instance, Thornbury and Meddings quote Gillian Brown (1990, in Thornbury and Meddings, 2009: 12-13) who noted that coursebooks exhibit:

"a materialistic set of values in which international travel, not being bored, positively being entertained, having leisure, and above all, spending money casually and without consideration of the sum involved in the pursuit of these ends, are the norm."

Thornbury and Meddings (2009: 13) wrote the following regarding the materialism coursebook content tends to exhibit:

"… the consumerist nature of coursebook content also reflects the aspirations of many learners of English, who view the acquisition of English (rightly or wrongly) as a passport to material well-being and international travel."

Certainly, these are thought-provoking words. However, when I taught with coursebooks, it never occurred to me that I should adopt Dogme ELT because I felt that my “learners’ aspirations are being manipulated in the interests of globalisation.” (Thornbury and Meddings, 2009: 13).

Fortunately, there are a few coursebook series out there (such as Outcomes) which don't revolve around spreading certain forms of culture and knowledge. Not all authors and teachers are complicit in these globalising processes.

Other texts

In this digital era, there’s no shortage of texts which can support the development of course materials that are familiar and meaningful to learners.

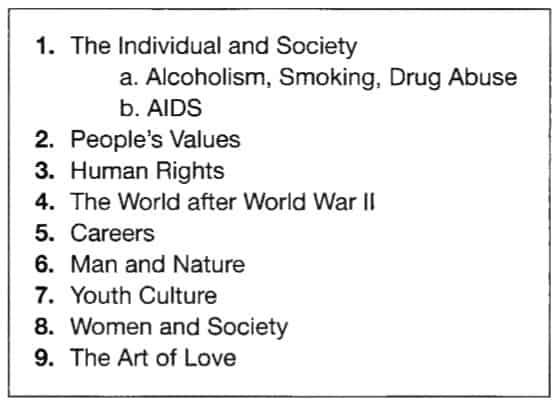

Intriguingly, Thornbury and Meddings describe the case of a Ukrainian teacher, Olga Kulchytska, whose advanced class drew up and wrote their very own ‘Alternate Textbook’ (Kulchytska, 2000, in Thornbury and Meddings, 2009: 15). Indeed, the learners selected their own themes and texts.

Olga ordered her students to do the following:

"Don’t pick topics for teachers - you are going to write this textbook for yourselves and for the next few generations of students."

Olga’s students named issues that she could never in her wildest dreams suspect they were interested in:

Overall, Olga’s ‘Alternate Textbook’ idea is an absolute gem. When language learning is learner-driven and based on authentic texts, only positive results can ensue.

3. Focus on emergent language

What does it mean to say that language emerges?

Basically defined, emergent language is language that “comes up” unpredictably in conversation between the learners, and/or the teacher and the learners.

This emergence of language is diametrically opposed to the process of acquisition whereby learners 'pick up' a second language through, predominantly, exposure and masses of input.

Through conversation, learners’ internal language systems respond and evolve in mysterious ways, as Thornbury and Meddings (2009: 18) argue:

"learners produce language that they weren’t necessarily taught, and sometimes show unexpected quantum leaps in their development. In this intrapersonal sense, language also emerges."

All in all, for those who are against the grammatical syllabus, like I am, emergence is a far more enticing prospect than the explicit teaching of grammar items. It’s not all about the emergence of individual language items. Both the grammar and lexical syllabus should also ‘emerge’. Teachers should not anticipate nor dictate learners’ communicative learners, but RESPOND to them. Still, I didn’t need Dogme to alter my beliefs as an ELT teacher.

Other characteristics of Dogme ELT that I can relate to

Thornbury and Meddings revelled in stating the blindingly obvious throughout their 2009 book. Nevertheless, they made a few extremely thought-provoking points:

1. See everything as a language opportunity

There are plenty of spontaneous and unplanned ‘Dogme moments’ that teachers can share with students.

If you run your finger over a surface and find it is dusty, share the moment with the learners. Ask them what you are reacting to. Ask them how they feel about it. Elicit and extend the words they have for talking about it.

Thinking about it, there’s so much language that could ‘come up’ due to this dusty situation. For example:

- dusty

- run your finger/s over something

- do the dusting - How often do you DO THE DUSTING?

- WIPE dust off something

2. Engage with the way learners feel on a given day

Sure, people don’t come to an English language class to ‘have a moan’. However, there’s no reason for learners to avoid talking about the mood they’re in. As Thornbury and Meddings (2009: 35) point out:

"After all, the way we feel affects more than our receptiveness to learning opportunities - it shapes our communicative needs, often giving us a reason to speak in the first place."

By tuning in to the way students feel, ELT teachers can allow learners to ‘come out of their shell’ and express themselves more fully. This can only serve to build the class dynamic.

3. Unplugged materials: Objects, images and texts

We come across all sorts of ‘things’ that we want to share with other people in the course of the day, from stories in the news to things we see in the street.

I must admit that I was a far too rigid and unpredictable teacher in the first five years of my career. Frankly, I can’t remember ‘sourcing’ many materials from the local environment to share with students. All I can recall is showing one group of students some pictures from my camping tour around the USA. Even that was right at the end of class when I couldn’t exploit the images for their ‘Dogme moments’.

With regard to exploiting the everyday items we see in the street, why shouldn’t the opportunist teacher pick up a horse chestnut fruit in the autumn months and use it as a ‘Dogme moment’ in class?

With the humble chestnut I might have picked up in the street on the way to the private language schools I worked at, many ‘Dogme moments’ could have emerged:

1. Background story:

When I was a child, my father took me to a huge park to throw sticks up into horse chestnut trees for the chestnut fruits to fall to the ground.

2. Cultural input:

When I was young, I played ‘conkers’ with my father and grandfather. Conkers is a traditional children's game in Great Britain and Ireland played using the seeds of horse chestnut trees. The game is played by two players, each with a conker threaded onto a piece of string. Players take turns striking each other's conker until one breaks.

3. Lexical input:

Now that learners have listened to the background story and received some interesting cultural input, I could put up some off-the-cuff language on the board relating to playing conkers:

(a) Feelings while throwing sticks up into the trees - strength / a real challenge / addictive (to collect conkers)

(b) Language related to playing conkers - competitive spirit / painful (when the other player’s conker hits your hand) / accurate

(b) Past simple - threw / collected / played / broke

4. Students respond:

Students can share their memories of playing a childhood game particular to their culture.

5. Next class:

The learners could bring a humble object which they found outside to class. Failing that, they could bring a cherished possession they own and describe why it evokes so many wonderful memories.

Dogme ELT - Final Thoughts

I’ll never forget what my boss at the second language school I worked at said in response to me telling her that I was responsible for the conversation bits in coursebooks in my first school, while my Polish co-teachers dealt with the grammar parts.

She said: “So you chatted with them”. “Them” being my students.

This lady has always been a big fan of drilling and the grammatical syllabus. Nevertheless, she had a point. It was pure chat because there were never any ‘Dogme moments’. Regrettably, I never really dealt with language issues as they ‘came up’ in that first school. I like the emphasis Thornbury and Meddings (2019) put on rewarding students’ emergent language and getting them to use emergent items in new contexts. Personalisation!

Regarding Dogme ELT, I feel it’s something teachers can dip into from time to time. Eclecticism really. A bit of Dogme, a bit of drilling, a bit of work with authentic materials and working with the best pages in coursebooks. Teachers need to keep students on their toes. Frankly, I’m not sure how paying students would feel if their teacher rocks up to every class without a ‘plan’.

I think it takes a bubbly and bold character to deliver compelling Dogme lessons. Thornbury and Meddings seem to think that all EFL teachers are extroverted magicians. Generally, I think I’m an excellent motivator. As an introvert, I’d like to think I have a knack for saying the right things at the right time to my students to get them into shape. However, I revel in the security authentic materials give me because I’m not one for setting classrooms alight with my outgoing nature and ability to be spontaneous.

Now then - I’m off to give my mate Thornbury a call to see if I can knock him off his fence.

References:

Meddings, L. and Thornbury, S. (2009). Teaching Unplugged: Dogme in English Language Teaching, Delta Publishing Company: UK

Swan, M. (1985). A Critical Look at the Communicative Approach (2), ELT Journal, Volume 39, Issue 2, April 1985, 76–87

Thornbury, S. (2000). A Dogma for EFL, IATEFL Issues, 153, Feb-March 2000, p.2