What are the best ways to encourage students to speak English?

If you’re wondering how to encourage students to speak English in class, you’re in the right place.

This post is really about techniques you can implement to get students to open up and speak more English than they do. Before I get to these techniques, I will consider the common stumbling blocks students face when it comes to practising speaking in class.

Encouraging Your Students to Speak Their Mind: What Are the Common Stumbling Blocks?

There are plenty of reasons why students are reluctant to practise speaking English in the classroom:

Introverted students

Unfortunately, introverted students get lost in ESL/EFL classes because sessions are typically oriented towards extroverts.

In her research paper, “The Introverted Students in the Modern ESL/EFL Classroom”, Elena Shalevska, English Language Lecturer at The University of St. Clement of Ohrid in North Macedonia, puts it very well indeed:

The problem with the ESL/EFL classes nowadays … is that they focus excessively on extroverts and their learning style. Our own research, upon conducting this paper, revealed that the majority of ESL/EFL coursebooks and the state’s official curricula rely on numerous group-work assignments that are ideal for extroverts, but not for their introverted classmates.

Students are lost for words

It can be mightily difficult to form and maintain a fulfilling conversation from scratch if English is your second language.

If a speaking activity is too open-ended, meaning it demands a spontaneous, expansive and unstructured response, students might find it tough to come up with what to say.

Lack of confidence

Students who are consumed with self-doubt about their speaking abilities will have a harder time speaking their mind.

It’s never a bad idea for the teacher to provide learners with specific collocations and phrases to include in a conversation-based activity.

Students care too much about grammatical accuracy

Unfortunately, English language learners have to contend with so many tenses and grammar rules from an early age.

Frankly, forcing the grammatical syllabus onto learners does little but confuse and burden them to the point they become ashamed to make grammar mistakes when they speak.

There are some common-sense ways to strip down the grammatical syllabus and focus on those tenses and structures which commonly crop up in spoken English. Many grammar points which find their way onto syllabuses are more appropriate for written English as opposed to spoken English. I will write more on this topic later in this post.

Students may have become used to teacher-centred methodologies earlier on in their education

According to one article I’ve read in the ELT Journal (Talandis and Stout, 2014), teachers of English in Japan have their backs firmly to the wall in their efforts to encourage students to speak English.

As Talandis and Stout (2014, p.1) state:

... prevalent teacher-centred methodologies, such as grammar-translation, mean that many students have not had much, if any, speaking practice.

Hence, Japanese students enter university having gained little training in how to conduct a conversation. This is despite the fact they receive six years of English education at secondary school.

Some 14 years ago, I taught English in Bosnia. Every class consisted mostly of grammar drills. Self-expression was limited because the name of the game was accuracy. On the rare occasion I tried to make conversation with students, they only seemed to be able to give short answers because they’d become so used to following rigid question-answer patterns.

What is the net result of teacher-centred instruction? Typically, as Talandis and Stout (2014, p.1) confirm, students enter university with an abnormally low level of speaking proficiency. Indeed, this level may even be below the A1 threshold on the Common European Framework of Reference.

Students can’t get their mother tongue out of their minds

It’s something I’ve heard quite a lot in my time as an EFL teacher:

“I'm not able to think in English”.

Many students’ English idiolects and utterances are riddled with direct translations from their first language into English. More often than not, direct translation causes errors in a process called negative language transfer.

Sadly, when bad speaking habits become permanent, it’s almost impossible to reverse this process of fossilization.

Fear of messing up

It’s not uncommon for learners to feel embarrassed in front of their classmates. Such embarrassment may be fuelled by a lack of respect among peers. For example, students may snigger at one another if they say something incorrectly.

The teacher faces a hard time creating a positive classroom environment and a culture of respect. I shall shortly highlight some of the ways you can cultivate such an environment.

What Are the Best Ways to Motivate Students to Come out of their Shell and Speak English?

Now that I’ve dealt with the obstacles students face when it comes to speaking up, I shall now highlight some techniques teachers may implement to encourage students to speak English freely.

Let’s begin on the point I just made about cultivating a culture of respect in the classroom.

1. Cultivate a culture of respect in the classroom

There are a multitude of ways teachers can build a culture of respect in the classroom.

First of all, teachers need to have a real heart to heart with students right from the get-go. In my experience, it’s fine to share your teaching beliefs with students. It’s not at all boastful to do such a thing. Students like to know what their teacher is all about - both in terms of mindset and methodology.

So, if you have a belief that students absolutely must experiment with newly-learned words and structures, even if they make mistakes, then explain your logic behind this belief.

If you nurture an environment in which mistakes are tolerated and students are allowed to take risks, they won’t be so inclined to make fun of a peer for saying something incorrectly. Besides, students need to know what kind of behaviour is unacceptable. Put your foot down when the time calls for it.

2. Materials matter

When I first started teaching in 2006, I often relied on conversation questions to get students talking in the discussion phase of a class.

It’s horrifying to think that I asked students a list of random questions, such as the ones related to ‘Movies’ below:

First of all, there was no continuity in communication. Students probably felt as if they were being interrogated because I moved from one question to the next without asking follow-up questions based on their answers.

I shifted my focus to the use of authentic materials, such as newspaper articles, when I started teaching logistics managers and business people in 2012.

Over the past six or seven years, I’ve also written many texts based on my own life experiences. I also reveal a little bit about my world view in these texts. Here’s one of my texts:

When students see the effort you’ve put into preparing materials, they’ll feel inclined to talk. Besides, some of the topics I write about are highly relatable.

I also think that many of my texts are a great source of debate. If you can get students into ‘debate mode’, many of the issues which students come up against, such as lack of confidence, being lost for words and worrying about grammar, may dissipate.

3. It’s not what you ask that matters. It's more important to focus on HOW you ask a question

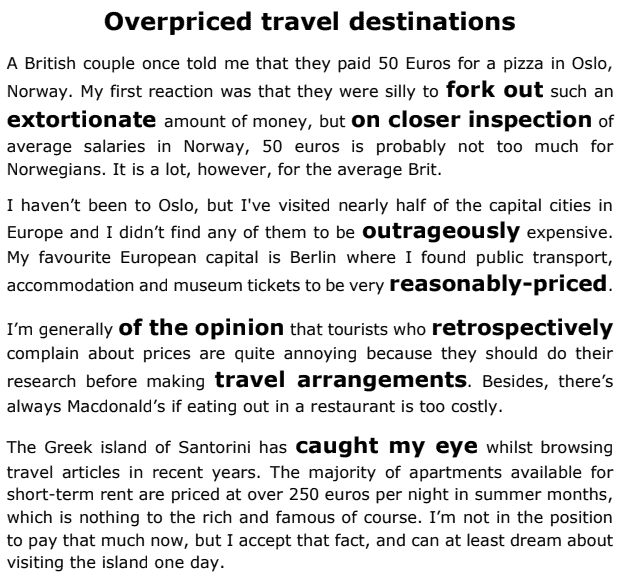

Most of my classes revolve around the discussion of key points in easily relatable online articles.

When I plan a class, I tend to copy and paste key information from articles onto a google doc. Before these points, I summarise this information using bold font and capital letters. Take a look:

Therefore, I don’t write questions word-for-word. It’s too unnatural and contrived, and students would see through it. The main idea is to summarise information, paraphrase where necessary and make sure that you’ve got a handle on the topic.

Using the first point above - TREAT TIME AS A PRECIOUS RESOURCE - this is what I would say to encourage students to speak English uninhibitedly:

1. Introduce the supporting information from the article:

So, according to Dr Syd, you might keep running out of time because you’re not treating time as the precious resource it is.

2. Add a personal attitude/opinion if necessary:

Yes, Dr Syd’s prescription hits you even though it might be common sense.

3. Make a question based on the information in the article:

So, what do you think about Dr Syd’s prescription?

4. Add one more question that’s personal to the student:

Do you keep running out of time because you’re not treating every minute as the precious resource it is?

What’s really going on with this approach?

- You’re showing that you know the article inside out. Students like to know that a teacher is well-prepared. Therefore, showing your knowledge surely has a positive impact on students' confidence levels;

- There’s no harm in slipping in a personal attitude before asking the question/s. You’re only human after all. You don’t have to make asking questions sound like an interrogation;

- All good journalists do it. They ask two or three questions, one after the other, to draw information out of their interviewees. That’s what happened in 3 and 4. I’d ask a student for their opinion on a key point in an article before asking them to share their personal experience.

4. Simplify life for your students by stripping down the grammatical syllabus

As I pointed out earlier, students are overburdened with grammar rules from their early days of schooling.

The worst thing is, teachers cover grammar points without explaining whether a tense or structure is appropriate for spoken or written English.

Take it from me, you’re not going to encourage students to speak English with the passive voice.

What you need to do is strip down the grammatical syllabus and introduce grammar only if it’s going to enhance students’ conversation skills.

For example, if you want to help students describe their life experiences with the present perfect, introduce the tense in tandem with the past simple. For instance:

1 - I’ve been to Sarajevo three or four times

2 - The first time I WENT TO Sarajevo was in January, 2009

2 - I STAYED in the city for a few days and it was absolutely freezing

2 - I mostly STROLLED around the Old Town and also CLIMBED a hill to catch a magnificent view of the snow-covered city

1 - I haven’t been to many other places in central and eastern parts of Bosnia though

Hence, we have this 1-2-2-2-2 pattern. Students can introduce a life experience using the present perfect (1). Then, they can go into details with the past simple (2). Finally, they can switch back to the present perfect (1) should they need to.

All in all, when students see these numbers, when you break down grammar for them in an understandable way, they will respond with enthusiasm.

5. Begin the long and arduous process to help students think in English

I’ve already written my thoughts on this blog about how to get students to think in English. However, let’s recap.

One of the main takeaways from that post was the importance of getting students to implement a language learning strategy in their private study time.

The strategy I always encourage my students to adopt is the Word-Phrase Table. In my experience of learning Serbian and Polish, this method helped me to “think” in those languages. As time passed, I had so many phrases and correctly structured sentences “swimming” in my brain that I could simply forget about having to form grammatically-sound sentences using, for example, the correct grammatical cases.

When I came across a new word or collocation, I’d insert into my Word-Phrase Table on a Google Doc and build on it with other collocations and sentences relating to my own life (i.e. “personalised sentences”).

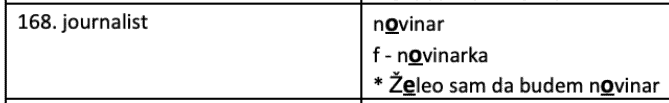

Early on during my learning of Serbian, here’s what I did with the word ‘journalist’:

In this case, I added the masculine and feminine equivalents in Serbian for the word ‘journalist’

Secondly, I added a sentence after a star (*). Hence, Želeo sam da budem novinar means I wanted to be/become a journalist. Believe it or not, I wanted to become a newspaper journalist in my teens.

I could have added “... when I was a teenager”. However, I’d probably already learned how to say that so I didn’t see the need to include it.

All in all, regular revision of these personalised sentences helped me to internalise key grammar structures and retrieve them in other contexts when I spoke Serbian. I also believe that I’ve never been that prone to negative transfer because all of these personalised sentences helped me to understand and internalise the makeup of the Serbian language.

There’s a great deal you can do to get students to open up

Overall, there’s a great deal you can do as a teacher to encourage students to speak English more freely.

If you help them win a few important battles, such as adopting a language learning strategy and sticking to it, and also getting them to realise that they don’t need to learn English according to the grammatical syllabus but can instead view English from a more lexical perspective, then their confidence levels will rise.

References:

Shalevska, E., “The Introverted Students in the Modern ESL/EFL Classroom”, The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education, April 2021, Vol. 11 (2), 93-97

Talandis, G., and Stout, M., “Getting EFL students to speak: An action research approach”, ELT Journal, Dec 2014, 69(1), pp.11-25