English Word Stress Rules – with Jennie Reed

To help shed some light on the topic of English word stress rules, I recently interviewed English pronunciation coach Jennie Reed. Jennie is an experienced English teacher from southern England.

Before introducing Jennie, I will briefly introduce the topic of English word stress. After sharing a short biography of Jennie, I will share the interview. Then, I will go into some of the rules of English word stress, ably assisted by some excellent articles and books I’ve read. I shall round things off with one of Jennie’s exercises on word stress, followed by some closing thoughts.

An Introduction to English word stress

In a nutshell, word stress is the term used to describe the emphasis or accent given to a particular word when pronouncing it. Aside from ‘emphasis’ and ‘accent’, stress may also be referred to as ‘prominence’ (Rogerson-Revell, 2011, p.137). In English words which contain more than one syllable, we don’t usually pronounce each syllable with the same weight. Therefore, syllables in a word may either be stressed or unstressed.

Longer English words may have more than one stressed syllable. Nevertheless, one of them tends to be emphasised more than the other(s). This is where primary and secondary stress come into play. The syllable with the primary stress attached to it obviously stands out the most.

Apart from primary and secondary stress, it’s also worth mentioning unstressed syllables. In English, almost all unstressed syllables have schwa [ə] for their vowel, though [i] will also often be unstressed, like the [i] in nippy [/ˈnɪp.i/]. Proficient speakers of English tend to shorten the unstressed syllables so much that the vowel sound almost entirely disappears.

In this post, I approach the topic of English word stress rules with some caution. Oftentimes, when it comes to language learning, there are no hard and fast rules. Indeed, as Kelly (2000, p.68) and Underhill (2005, p.55) argue, it’s more appropriate to describe word stress in terms of “tendencies” as opposed to rules. More to come on these tendencies throughout this post.

All about Jennie Reed

Originally from Essex, England, Jennie now lives in Alloa, Scotland.

Soon after graduating in German and Italian, Jennie got her TEFL certificate with the International TEFL Academy in 2010. Some of her first assignments in TEFL included a two-and-a-half-year stint teaching English in Italy, a ten-month position teaching English in Munich and a stretch teaching international students in Chester, UK. Jennie subsequently worked as a teacher of English, Interim marketing manager and Interim Director of Studies at Conlan School Ltd, also in Chester.

Between June 2016 and July 2020, Jennie worked as an English teacher at British Study Centres in Edinburgh. During that period of time, she completed The Diploma in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (DipTESOL).

In August 2020, at the height of the pandemic, Jennie turned her attention to freelance tutoring online. That’s when she set up Excellence in English Education. Essentially, Jennie is focused on helping students to develop their pronunciation skills. She also helps passionate English Teachers deliver inspiring and engaging lessons so that they can create positive, long-lasting changes in the classroom.

These days, Jennie also volunteers as an ESL teacher for the non-profit organisation RefuAid. RefuAid assists refugees and asylum seekers all over the UK to access higher education, requalification and employment.

Interview - English word stress rules with Jennie Reed

1. When it comes to English word stress rules, there are rather mixed feelings in the literature. Dauer [2005, p.548] argues in favour, stating that “students need to be taught word stress because it does not appear in the writing system and many are not aware of its importance.” In fact, Dauer [2005] takes another writer Jenkins [2000, in Dauer, 2005] to task. Jenkins believes that word stress is unteachable, unlearnable, and unnecessary from the perspective of a non-native speaker. Dauer fights back, giving the example of polysyllabic words. According to Dauer [2005, p.547], a handful of basic rules can account for 85% of polysyllabic words [see Dauer, 1993, pp.67-68].

With Dauer at one end of the spectrum, and Jenkins at the other, where do you stand on the debate surrounding the teachability of word stress?

I think it can be helpful for some students to understand English word stress rules. Some students need the rules to be able to apply them and use them well. For other students, it’s not so important. They’re more interested in using the language as they find it. It’s very much student-dependent.

From a student’s perspective, it’s not necessarily a bad thing to know the rules. Sometimes, just having one or two of the rules can be helpful. However, it’s important to remember that there are always exceptions to most of the rules we have.

When we stress a certain syllable in a word, it’s always the vowel that’s stressed – never the consonants. I never even realised that word stress worked like this until I began to find my feet as a teacher.

2. Just extending question 1 a little. Adrian Underhill shoots straight down the middle in his book Sound Foundations: Learning and Teaching Pronunciation. Underhill [2005, p.55] emphasises that “Some rules are complex to apply, and even then have many exceptions. In fact, tendency may be a better term than rule.”

Underhill went on to note that “the best rule is to be alert, to notice what you are doing and what the language is doing, and to reflect.” So, associated with such noticing and reflection, Underhill [ibid.] believes teachers can foster the development of learners’ “intuitive learning faculties so that underlying tendencies can emerge within each learner without necessarily having to be described or explained”. Do you think low-level learners really have the capacity to resort to such “intuitive learning faculties”?

I believe that unless students are given some guidance and actually asked to notice specific things, it can be really difficult for students to think about word stress. This is because they have so many other things to consider, from lexical selection right through to whether they’ve got the grammar right. Frankly, I think word stress is one of the last things that they think about.

My argument remains the same as in my answer to your first question. From a teacher’s perspective, I do think that it’s worth focusing on word stress with a particular student if it will be helpful for them.

3. I’ve had a hard time teaching word stress to Polish learners of English as word stress falls on the penultimate syllable in their mother tongue? Can you describe your experience with imparting English word stress rules to learners of first languages where accent or word stress is fixed?

Most of my experience recently has been with Italian students. Like Polish words, Italian words also have a very fixed word stress. Indeed, stress is placed on the second last syllable in the majority of Italian words.

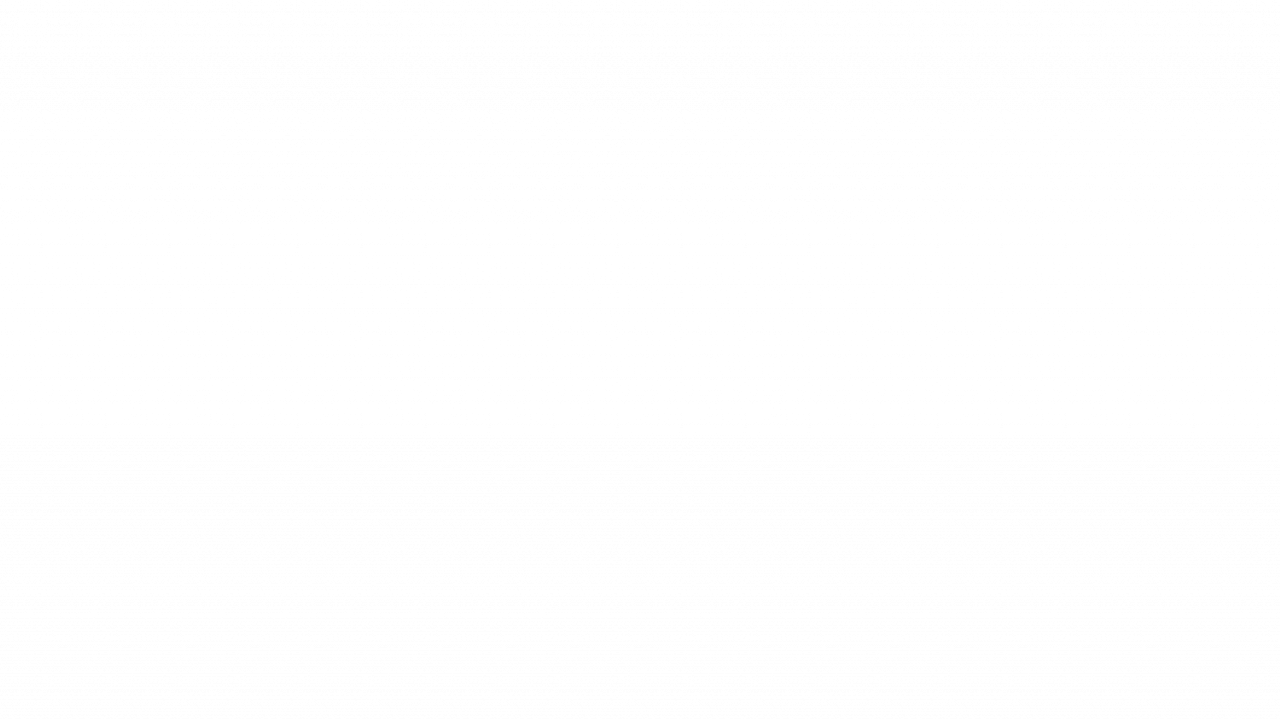

For Italians learning English, it’s even more important to highlight the fact that there can be variations when it comes to English word stress. For example, we stress two-syllable English words that can be both a noun and a verb differently; nouns on the first syllable and verbs on the second syllable.

It’s important to teach English word stress rules to Italians, for example, otherwise they’d tend to pronounce every word the same way. With two-syllable nouns and verbs, Italians usually stress the first syllable for both word classes, unless an accent is present on the final syllable. I’m not sure that this causes confusion or miscommunication but it can make communication that bit slower if they’re dealing with native speakers. That’s probably why people using English at a high level need to be aware of English word stress rules. The Italian people I’m working with are mainly teachers of English. Therefore, it’s important for them to be able to understand word stress tendencies so they can put the theory into practice in the classroom.

4. Can you talk a little bit about how you approach teaching the very complex stress placement rules for different grammatical categories of a word, such as two-syllable nouns and verbs as well as compound nouns?

I think any approach to teaching such stress rules should revolve around listening and repetition rather than looking at any individual words. As you mentioned earlier, we don’t have any way of recognising word stress in written English.

Most of the word stress exercises I do are based on listening and getting students to look at words and mark where they hear the stress. This can take quite a bit of practice but it’s much more effective than just reading the words. After all, they’re not going to see word stress highlighted with capital letters or bold script when they’re reading material. Therefore, for me, the practical aspect of learning word stress is more important.

5. How difficult is it to teach word stress when it comes to longer words, for example, those with three, four and five syllables? Do you get involved much with pointing out where primary and secondary stress occur in a given word?

I do touch upon the issue with my higher level learners. It’s mainly so they’re aware of it because word stress is heavily connected with sentence stress. As we don’t have fixed stress patterns which depend on the number of syllables, it’s more important to learn the function of a word or the ending of a word. For example, when words end in -sion, -logy or -graphy – plus many more endings – the previous syllable is stressed: compreHEnsion, psyCHOlogy or phoTOgraphy.

So I don’t tend to ask my students to learn these so-called English word stress rules off by heart. It’s more about grouping some words together and just getting them to listen to the words and repeat the words.

Overall, if students get the stress in the wrong place with longer words, it’s not likely to cause a huge breakdown in communication.

6. We often talk about a group of words in English that have two stress patterns - that is ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ forms. Many of these words are function words, such as prepositions and pronouns. The vast majority of the weak forms are characterised by the reduced schwa vowel /ə/ for example, a /ə/ book - not a /ei/ book. Where do weak forms rank in terms of importance in your pronunciation courses?

The schwa is the one phonemic symbol I insist all of my students know. Being able to reduce that sound when you’re speaking can enhance your communication and comprehensibility of your spoken language.

Schwa definitely contributes to fluency in that, within sentence stress, you need both stressed and unstressed words working in perfect harmony with one another. Schwa is essential when it comes to maintaining a regular rhythm in the language.

I’d like to add that I think it’s more important to learn chunks of language than it is to focus on rules. For example, ‘listen to’ sounds more like ‘listen tuh’, with a schwa in the preposition ‘to’, rather than ‘listen to’ [/tuː/].

7. Can you share some final words of wisdom when it comes to word stress in English?

I encourage my students to make a recording of themselves copying what’s been said when they’re listening to something. Ideally, the speakers should be proficient speakers of English. Students can then make a comparison of the two recordings, thinking about word stress, sentence stress and intonation. These areas should be analysed one at a time.

After comparing recordings, students should try to adjust what they’ve said so it matches the interlocutors’ speech. This is not about sounding a certain way or exactly the same as a proficient speaker, be it a native speaker or not. Our accents are an integral part of who we are and we should be proud of them. The purpose of making these voice recordings is to make speech more intelligible.

A summary of English word stress rules

In this section, I shall provide an in-depth summary of English word stress rules. I will highlight the conditions that influence which syllable is stressed in a word. First of all, it seems appropriate to provide a general introduction to word stress based on a review of the literature.

A Brief Overview of English Word Stress

To begin this overview of English word stress rules, or tendencies, it seems appropriate to consider the structure of an English word. First of all, English words consist of one syllable, two syllables, or many syllables. In all words of two or more syllables, one syllable is more prominent, louder or more noticeable than the other syllables in that word. Therefore, this strong syllable is stressed, or accented, while the other weaker syllables are unstressed, or unaccented:

- Stressed syllables - Stressed syllables sound louder, tend to be longer, and have clearer vowels and stronger consonants. When a word is uttered in isolation, stressed syllables adopt a higher pitch. In sentences, a pitch change (a shift in melody from high to low or low to high) often occurs on stressed syllables.

- Unstressed syllables - Unstressed syllables sound softer, are usually shorter and are often reduced. This means that the vowels tend to adopt the qualities of schwa (/ə/) or reduced sounds such as /ɪ/ and /ʊ/, while the consonants are weaker. The pitch doesn’t change direction on unstressed syllables.

Stress is not fixed to a particular syllable in English words, thus making English a free-stress language. Even though stress can occur on first, second or third syllables and so on, the placement is almost always fixed for individual words, regardless of the context. The word ‘perceived’, for example, is always perCEIVED, never PERceived.

To round off this introduction to English word stress, it’s worth highlighting a major difference between rhythm and word stress, as put forward by Levin (2018, p.39):

… word stress typically is limited to multi-syllabic words, whereas rhythm includes stress for single-syllable words. In English, for example, content words (e.g., nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, negatives), including those of one syllable, are normally stressed in discourse. Single-syllable function words (e.g. prepositions, auxiliary verbs, pronouns, determiners) are typically unstressed in discourse.

The Importance of Word Stress in Communication

A plethora of authors (see, for example: Fudge, 2016; Dauer, 1993 and Levis, 2018) have highlighted the importance of word stress in communication.

Fudge (2016, p.4) leads the way in his assessment of the seriousness of word stress. According to Fudge (ibid.), a faulty stressing will lead to a “wrong and misleading rhythm” due to the fact that English rhythm is stress-timed. Rhythm rather determines comprehensibility. Therefore, the placing of stress within words can significantly impact how well a native English hearer will understand the foreigner.

Dauer (1993, p.61) claims that stressing the correct syllable in a word is equally important as pronouncing the sounds correctly. This is particularly the case with heteronyms - words that have the same spelling but different pronunciation. Two examples Dauer offers include:

1.

a. invalid /ˈɪn.və.lɪd/ = a sick person

b. invalid /ɪnˈvæl.ɪd/ = not valid or not correct

2.

a. console /ˈkɒn.səʊl/ = a surface or device with controls for electronic equipment, a vehicle, etc

b. console /kənˈsəʊl/ = to make someone feel better

Levis (2018, p.100) admits that misplaced word stress in English can halt communication entirely:

When a word, especially a word central to the understanding of the message, cannot be recognised, listeners may stop all other processing to decode the word that was not understood.

Oh what an atmosphere

Levis (ibid.) describes a study he ran on the ways that teaching assistants (TAs) transformed a written text into spoken language. Essentially, TAs were provided with a paragraph from a basic physics text on the kinds of energy and how they were related. They had a short amount of time to prepare their spoken presentation, which was video-recorded. A research assistant (RA) transcribed each presentation. In one case, the RA could not identify a word in the first sentence of a presentation from a speaker from India (“Well, we have a very good ____________ today”).

Fortunately, the researchers knew the topic and worked out the category of the word due to the fact that the sentence was otherwise grammatical. The biggest issue was that the speaker stressed the three-syllable word on the middle syllable, which sounded like must or most. After several days of listening and trying to decode the word, one of the researchers broke down the segmentals, coming up with things such as ‘at most here’. Eventually, the researcher cracked the code with the word atmosphere. Intelligibility arose because this word is stressed on the middle syllable in Indian English.

What are the main acoustic signals of stressed syllables?

The hearer perceives an accented syllable as more prominent than an unstressed syllable. Prominence is connected with the amount of muscular energy used to produce a syllable (Rogerson-Revell, 2011, p.138). The main acoustic signals of prominence are:

(1) Pitch change - If a syllable is said with a change in pitch, that is either higher or lower, the syllable will be more prominent to the hearer.

e.g. ba

ba ba bae.g. ba baa ba ba

Rogerson-Revell (ibid.) points out that long vowels (/i:/ /ɔ:/ /ɑ:/ /ɜ:/ /u:/) and diphthongs generally appear more prominent than shorter vowels. However, long vowels and diphthongs also crop up in unaccented syllables. In the examples below, they are not stressed; however they still give an impression of prominence (the stressed syllable is marked with a ˈ).

phoneme / ˈfəʊni:m/

placard / ˈplækɑ:d/

railway / ˈreɪlweɪ/

pillow / ˈpɪləʊ/

(c) Vowel quality - The most important aspect of differences in vowel quality is that unstressed syllables typically contain a reduced vowel (either /ə/ or /i/ or /u/). Hence, stressed syllables tend to stand out due to the fact that they have a full vowel.

e.g. bi

ba ba ba(d) Syllable loudness - It is important to realise that it is difficult to increase loudness without altering other qualities such as pitch level:

e.g. ba BA ba ba

Levels of stress

So far, I’ve only really touched upon syllables in terms of being either stressed or unstressed. In fact, syllables can have different degrees of stress within longer words. Therefore, when dealing with words as they are said in isolation, we need to consider all syllables in terms of their level of stress.

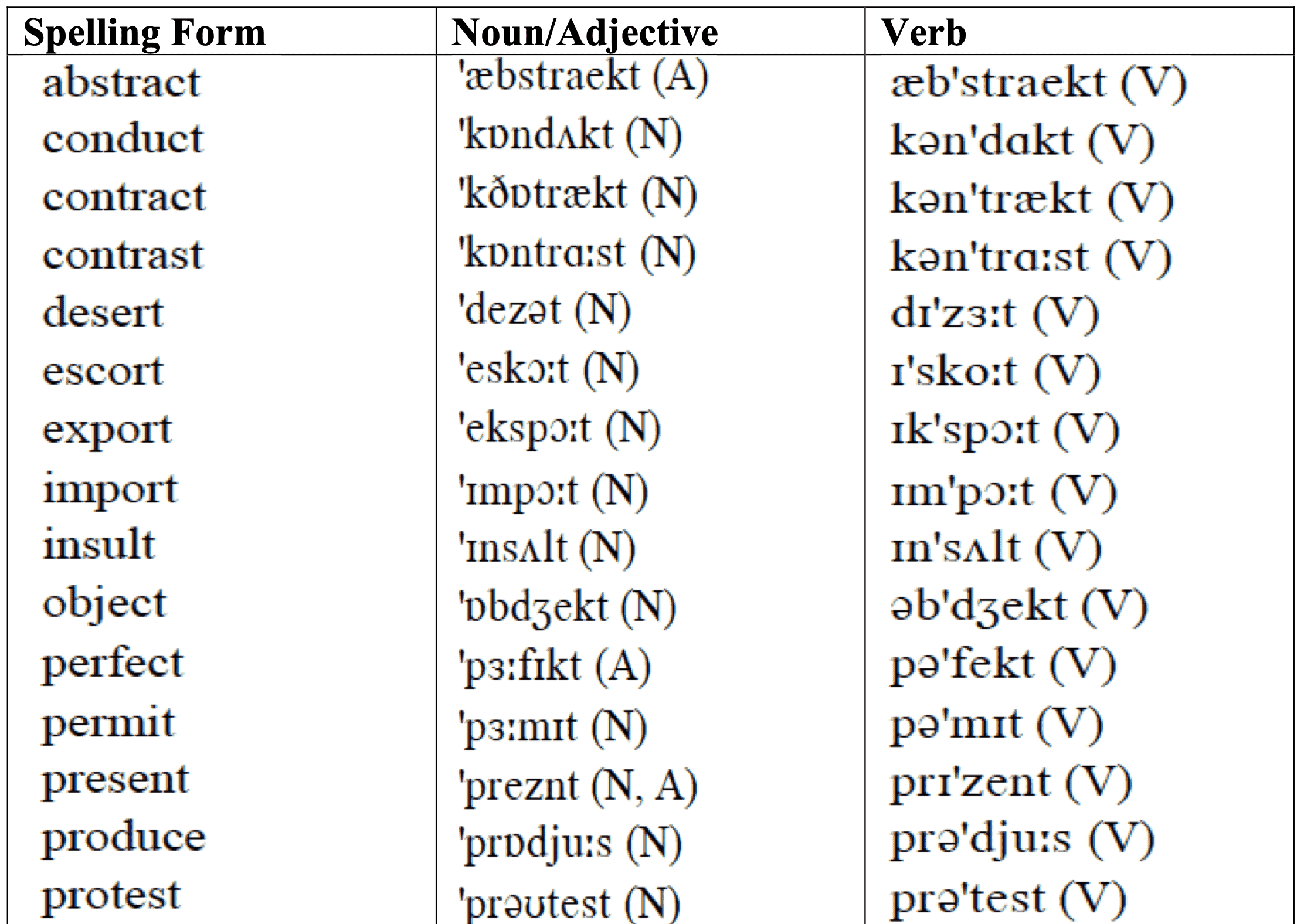

There are commentators who have outlined more degrees of stress than is probably necessary when it comes to longer words. For instance, Daniel Jones (1922, p.111) highlights the word opportunity, which has five levels of stress as seen below. ‘1’ indicates the greatest level of stress, and ‘5’ the least:

(In Kelly, 2000, p.69)

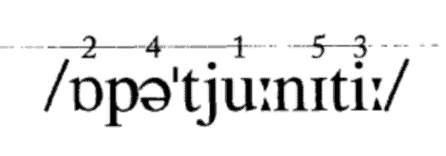

When it comes to teaching or studying word stress, Jones (1922, p.111) is quick to concede that “it is generally sufficient to distinguish two degrees [of stress] only, stressed and unstressed.” However, he goes on to mention that it may sometimes be necessary to distinguish three degrees of stress. According to Kelly (2000, p.69), commentators tend to settle on a three-level distinction between primary stress, secondary stress and unstress for multi-syllable words, as is observable in the following examples:

(In Kelly, 2000, p.69)

In terms of marking stress in written form, primary stress is indicated by a high mark [ˈ]:

reˈturn /rɪˈtɜ:n/Secondary stress may be indicated by a low mark [ˌ] , as in:

ˌreveˈlation /ˌrevəˈleɪʃn/

conˌtamiˈnation /kənˌtæmɪnˈeɪʃn/

To round off this section, it’s worth paying heed to Jones’s (1922, p.111) observation that, when it comes to multi-syllable words, “foreigners usually put the secondary stress or even the primary stress of the first syllable”. This is the case with words such as examination, peculiarity and administration, all of which contain a secondary stress on the second syllable.

The placement of stress within an English word

Finally, we have come to the main focus of this post about English word stress rules. This question causes exceptional difficulty to English language learners:

How can one select the correct syllable or syllables to stress in an English word?

As Jennie and I touched upon in the interview, it’s not possible to pinpoint word stress in the English language simply in relation to the syllables of a word. As Roach (1991, p.88) puts forward:

Many writers have said that English is so difficult to predict that it is best to treat stress placement as a property of the individual word, to be learned when the word itself is learned.

Hence, it’s hard to disagree with Rogerson-Revell (2011, p.141) who states that: “Stress placement rules exist for English but they are rather complex.” The English language learner is best advised to not think in terms of English word stress rules but rather general tendencies for stress placement. Practically all of the rules have exceptions.

Stress placement depends on a variety of factors, including:

- whether a word is morphologically simple (i.e. words consisting of a single morpheme), complex (a word made up of two or more morphemes and containing prefixes or suffixes) or a compound (two or more words that have been grouped together to create a new word that has a different, individual meaning, e.g. foot + ball = football).

- the grammatical category of a word (noun, verb, adjective, etc.)

- the number of syllables in a word

- the phonological structure of the syllables (e.g. final syllables with short vowels, one final consonant, or a schwa sound (/ə/) are not stressed).

I will now highlight those general tendencies for stress placement in simple lexical words.

Two syllable words

a. Nouns

Most two syllable nouns (most notably proper nouns) have stress on the first syllable:

e.g.

ˈPeter

ˈChristmas

ˈcoffee

Nevertheless, if the second syllable is strong (i.e. it has a long vowel or a diphthong or ends in two consonants), then the second syllable is stressed.

e.g.

deˈsign

eˈstate

Overall, it’s rare for two syllable nouns to be stressed on the second syllable. It tends to be related to borrowed words:

e.g.

laˈgoon

saˈloon

b. Verbs

Most two syllable verbs have stress on the second syllable, if that syllable is strong. That means if the second syllable contains a long vowel or diphthong, or it ends with more than one consonant, that second syllable is stressed.

e.g.

apˈply

perˈsuade

reˈstrict

Conversely, if the final syllable is weak (i.e. containing either a short vowel or schwa and one, or no, final consonant), then the first syllable is stressed. A final syllable is also unstressed if it contains /əʊ/, as in ‘borrow’ /ˈbɒrəʊ/.

e.g.

ˈenter

ˈenvy

ˈopen

When we consider those two-syllable verbs that are exceptions to the above rules, the words might be perceived as being morphologically complex (e.g. per'mit).

c. Adjectives

Two syllable adjectives tend to follow the same pattern as verbs.

e.g.

ˈlovely

corˈrect

aˈlive

ˈopen

English word stress rules are not set in stone. Therefore, there are quite a few exceptions to established tendencies when it comes to the stress placement in two-syllable adjectives.

e.g.

ˈhonest

ˈperfect

____

Finally, other two-syllable words such as prepositions and adverbs appear to behave like adjectives and verbs.

Word-class pairs

Mastering English word stress rules becomes even trickier when the foreigner begins to grapple with a group of words known as word-class pairs (homographs). Essentially, these words operate as both nouns and verbs and have identical spelling. They differ from each other in terms of stress placement:

The mis-stressing of noun-verb pairs does not seem to affect intelligibility or comprehensibility for native listeners (Levis, 2018, p.116).

Three-syllable words

When it comes to three-syllable words, there is a tendency to put the stress towards the end of the word on verbs and the front of the word for nouns.

a. Verbs

In verbs, if the final syllable is strong (with a long vowel, diphthong, or more than one consonant), it will be stressed, as in:

enterˈtain underˈstand

In contrast, if the last syllable is weak (with a short vowel and ends with not more than one consonant), that syllable will be unstressed and the stress shifts forward to the preceding (penultimate) syllable, if that syllable is strong, as in:

deˈvelop diˈrection

suˈrrender eˈxamine

b. Nouns

When it comes to stress placement tendencies for three-syllable nouns, it is useful to consult Roach (1991, p.90).

First of all, if the final syllable contains a short vowel or /əʊ/, it is unstressed. If the syllable which comes before this final syllable contains a long vowel or diphthong, or if it ends with more than one consonant, that middle syllable will be stressed.

e.g.

potato /pəˈteɪ.təʊ/

disaster /dɪˈzɑː.stə/

Nevertheless, if the final syllable contains a short vowel and the middle syllable also contains a short vowel and ends with not more than a single consonant, these two syllables are unstressed. Stress placement should fall on the first syllable:

e.g.

quantity /ˈkwɒn.tə.ti/

cinema /ˈsɪn.ə.mə/

The aforementioned rules pertaining to nouns show stress tending to go on syllables which contain a long vowel or diphthong and/or ending with more than one consonant. When it comes to three-syllable nouns, if the last syllable is of this type, the first syllable is usually stressed. The last syllable tends to be prominent meaning that secondary stress comes into play.

e.g.

intellect /ˈɪn·təlˌekt/

alkali /ˈæl·kəˌlɑɪ/

c. Adjectives

Many adjectives tend to follow the immediately preceding rule pertaining to nouns. The first syllable tends to be stressed while the last syllable usually adopts secondary stress:

e.g.

derelict /ˈder·əˌlɪkt/

Stress in complex words

Thus far, we have considered English word stress rules relating to ‘simple’ words, namely words comprising a single grammatical unit. However, there are plenty of words which consist of more than one grammatical part. For instance, ‘hope’ + ‘less’ = ‘hopeless’ and ‘fool’ + ‘ish’ = ‘foolish’. Such complex words fall into two categories:

(a) Words constructed from a basic stem together with an affix (i.e. a prefix such as ‘un’ + pleasant = unpleasant, or a suffix such as ‘able’ + suit = suitable

(b) compound words (e.g. ice-cream, armchair)

(a) Words with affixes (prefixes and suffixes)

Affixes can affect word stress in three ways:

(i) the affix is stressed - e.g. ˌJapaˈnese

(ii) the affix has no effect - e.g. ˈmarket - ˈmarketing

(iii) the affix is not stressed but the stress on the stem shifts - e.g. ˈmagnet - magˈnetic

(i) The affix is stressed = ‘Autostressed’ Suffixes

There are cases when the primary stress falls on the suffix (e.g. entrepreˈneur) or moves onto a suffix, as in:

Jaˈpan – ˌJapaˈnese

ˈmountain –ˌmountainˈeer

Words containing more than two syllables may see their root acquiring a secondary stress, as in the examples above.

Single-syllable prefixes do not usually carry stress (e.g. misˈjudge). However, longer prefixes may carry secondary stress (e.g. ˌantiˈclockwise).

Fudge (2016, p.41) provides a complete list of autostressed suffixes. Among them are:

- ade

- aire

- ee

- een

- esce

- esque

- ette

- eur

- oon

- teen

(ii) Suffixes that do not affect stress placement

There are many cases in which the suffix does not affect stress placement. For instance:

-able - underˈstand - underˈstandable; ˈcomfort - ˈcomfortable

-age - ˈcover - ˈcoverage, ˈbag -ˈbaggage

-al - ecoˈnomic - ecoˈnomical; geoˈgraphic - geoˈgraphical

-ful - ˈcare - ˈcareful; ˈwonder- ˈwonderful

(iii) Suffixes that influence stress in the stem

Here, the suffix causes the stress on the word stem to move. For example:

-eous - adˈvantage; advanˈtageous

-ic - eˈconomy, ecoˈnomic; ˈstrategy, straˈtegic

Further reading on suffixes

Fudge (2016, p.52-103) devotes over 50 pages of his book to a comprehensive list of suffixes with their properties. Such extensive coverage proves why the student of English should not get bogged down with English word stress rules because they’re seemingly endless in number.

Prefixes

Roach (1991, p.98) deals with the topic prefixes very succinctly. He states that the effect of prefixes on stress does not have the “comparative regularity, independence and predictability of suffixes”. Moreover, there is no prefix of either one or two syllables which always carries primary stress. Therefore, Roach (ibid.) concludes that “stress in words with prefixes is governed by the same rules as those for words without prefixes”.

(b) Stress in compound words

In Fudge’s (2016, p.34) eyes compound words are unique in that they are:

… combinations of words that may occur independently elsewhere, and hence must be two words; at the same time, they are combined in such a way that they form a single relatively close-knit whole with a number of characteristics that indicate rather clearly that they are one word.

Fudge (ibid.) goes on to mention that compounds possess many of the accentual and rhythmic traits of single words. Therefore, they tend to have a main stress near the beginning of the combination. Similarly, single words tend to bear penultimate or antepenultimate stress rather than final stress. In contrast, phrase constructions, which afford the individual words much more independence, generally have main stress on their final element.

Fudge (2016, p.34) illuminates the difference between compounds and phrase constructions through the examples of blackboard and black board. The compound noun blackboard (i.e. a board for writing on with chalk) takes primary stress on the first element black. As for the noun phrase black board, it normally has nuclear stress on the second element board.

Compound words may be written in a variety of ways:

(a) as one word - e.g. ‘sunflower’, ‘typewriter’ and ‘doorbell’

(b) with the words separated by a hyphen - e.g. ‘car-ferry’ and ‘fruit-cake’

(c) with two words separated by a space - e.g. ‘battery charger’ and ‘desk lamp’

Compounds which combine two nouns

As previously alluded to with the compound noun blackboard, compounds which comprise two nouns and function as nouns, generally put the stress on the first noun:

e.g.

ˈtypewriter

ˈgreenhouse

ˈsuitcase

Compounds which function as adjectives, verbs or adverbs

Compounds which function as adjectives (with the -ed morpheme at the end), verbs or adverbs, commonly put the stress on the second element:

e.g.

bad-ˈtempered (bad = adjectival)

ill-ˈtreat (compound which functions as a verb with an adverbial first element)

North-ˈEast (compound functioning as an adverb)

Problems with English Word Stress Rules

On a number of occasions, this post has highlighted the fact that English word stress rules are awash with inconsistencies, surprising twists and exceptions. It would be fair to replace the word ‘rules’ with ‘tendencies’.

Levis (2018, p.102) sums up the situation very aptly indeed:

Accounting for English word stress requires a hodgepodge of different patterns related to the length of the word, its lexical category, etymological origin, types of affixation, when the word became part of English.

Levis (2018, p.256) also concedes that English word stress is a heavily under-researched category of study:

… there is much that we do not know about word stress and its role in intelligibility. For example, we do not know exactly what word-stress problems are common for learners of various proficiency levels, which word-stress problems affect understanding for NS and/or NNS listeners, whether learners can perceive stress but not produce it, or vice versa.

Some of the most serious issues related to English word stress include:

1. Interference from the learner’s L1

There are countless issues related to the learner’s L1 which often prevent the production of correct word stress in English. Rogerson-Revell (2011, pp.151-52) lists some of the reasons learners frequently have difficulties with word stress due to interference from their L1, including:

(i) There may be a propensity to give both stressed and unstressed syllables full vowels (i.e. vowels in unstressed syllables are not weakened), as for instance in the Italian and French languages.

(ii) Word stress may be fixed in the L1 (i.e. stress tends to fall on a particular syllable). For example, the final syllable in French and Thai and the penultimate syllable in Swahili and Polish.

(iii) The L1 may have variable rather than fixed stress placement (as in English) but different rules, as in Turkish, Italian and Arabic. This may lead to particular problems with cognates.

(iv) The L1 may only have primary stress, as in Russian and Greek. This may cause problems with multisyllabic words.

(v) In many languages there is no compound word stress distinction, for example, white ‘house’ vs ‘White House’. The difference is rather signalled by word order as opposed to word stress.

(vi) Compound word stress may always be on the first syllable (e.g. ‘prime minister’, ‘front door’), as in German and Scandinavian languages.

(vii) ‘International’ words, namely cognates such as ‘television’, are subject to interference from the learner’s L1. ‘Television’ does not have penultimate stress and has five rather than four syllables in many languages.

2. Word stress is often studied/taught artificially as words tend to be analysed as they are said in isolation

English word stress rules relate to words as they are said in isolation. Certainly, as Roach (1991, p.95) points out, studying words in isolation does reveal stress placement and stress levels more clearly than analysing them in the context of rapid, continuous speech. Nevertheless, it’s still a somewhat artificial situation to focus on the stress of isolated words. After all, we rarely say words in isolation, apart from, for instance, ‘possibly’, ‘yes’, please’ and interrogative words such as ‘what’.

As one begins to analyse how word stress varies depending on the position of a word in a sentence, then it becomes easier to appreciate why it’s often a fruitless task to study the stress of words as they’re said insolation.

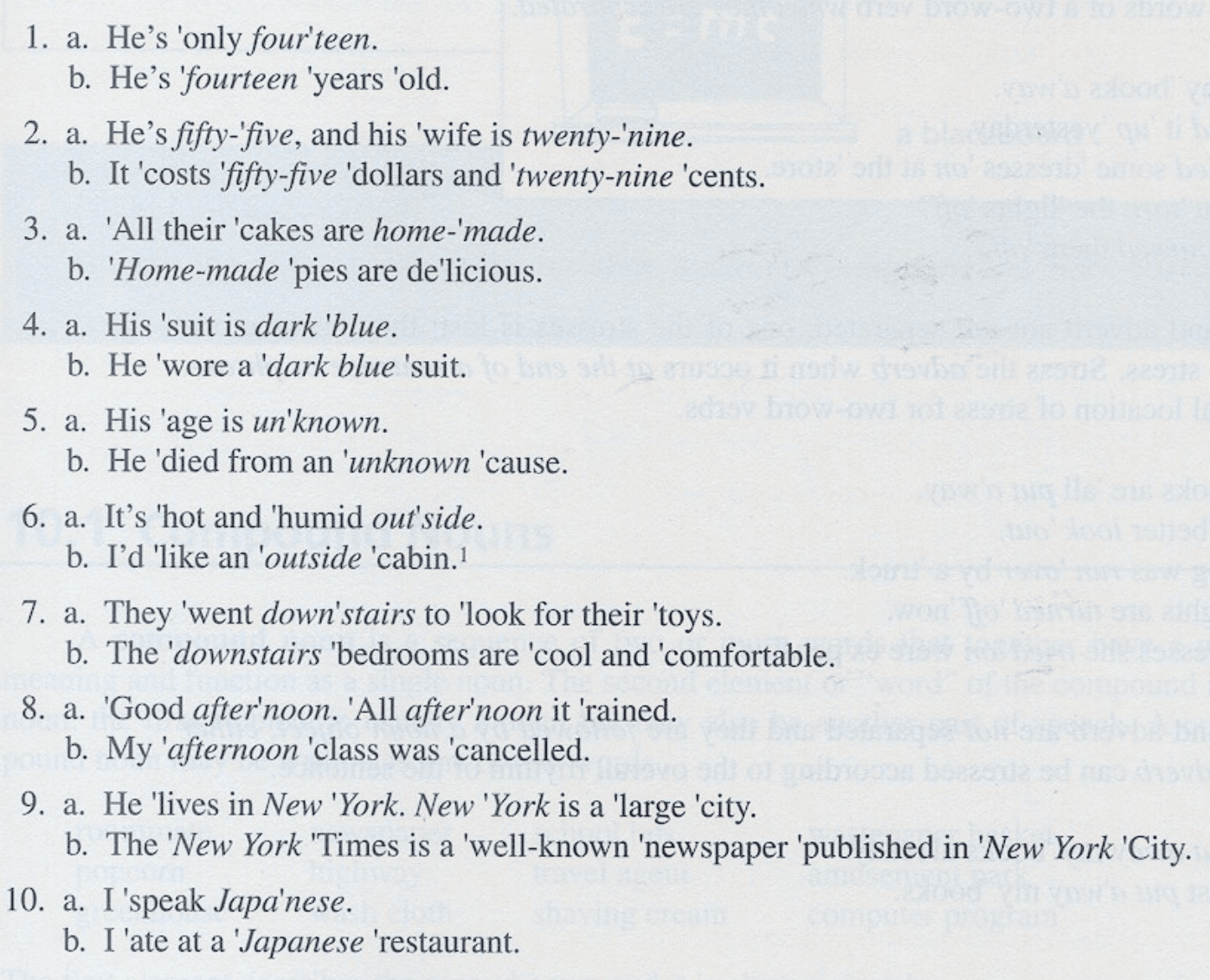

Dauer (1993, p.105), for instance, looks at how the stress in some words and compounds stressed on the last syllable may shift position depending on their location in a sentence. Essentially, words are stressed on the last syllable (or last “word”) when it occurs at the end of a sentence or phrase. In contrast, one should stress the first syllable (or first “word”) when it is immediately succeeded by another word in the same phrase. This is often the case when the word functions as an adjective and is followed by a noun that is stressed on the first syllable. Dauer (ibid.) offers the following sentences as a means to emphasise words with variable stress:

in Dauer, 1993, p.105

3. Bewildering complications and exceptions plague most areas of word stress in English

I would surely need another 25,000 words to cover all the exceptions to, and complications of, what appear to be even the most stable of English word stress rules.

However, to illuminate the difficulties both learners and teachers face when it comes to tackling English word stress, we should return to the topic of stress in compounds. On the face of it, there is a clear-cut distinction between phrases (taking final stress, e.g. black ˈboard) and compounds (taking initial stress, ˈblackˌboard). However, as Fudge (2016, p.136) questions, what about constructions which are syntactically similar to compounds yet they take phrasal stress patterns? Fudge (ibid.) compares ˈChristmas ˌcake (with the regular compound stress-pattern), and Christmas ˈpudding and Christmas ˈpie (with the phrasal type of pattern and stress on the second word).

With the aforementioned examples of Christmas foods in mind, it is apparent that there are very few English word stress rules that are of a hard-and-fast nature. Fudge (2017, pp.144-49) offers 22 main regularities related to the assignment of initial or final stress to compounds. Unsurprisingly, a great many of these regularities contain exceptions. This suggests that learners should focus on noticing stress patterns of individual phrases and compounds etc. when they engage in listening practice rather than consciously aim to ‘learn’ or memorise English word stress rules.

Word stress exercise with answers and audio files

Jennie kindly shared an exercise related to word stress. Download the exercise, which also contains answers, in PDF form using the link below. Do also download the audio files.

Final Thoughts on Word Stress Rules

This post has established that teachers of English face a genuine quandary when it comes to teaching English word stress rules. Given that these rules, or tendencies, are subject to a great many exceptions, one really has to consider whether it’s worth dedicating significant instruction time specifically to word stress.

Still, I believe that teachers should not completely overlook word stress. As for teachers who do have knowledge of the phonology of the student’s first language, then they are in a strong position to at least draw attention to why negative language transfer from the student’s mother tongue may be preventing the production of correct word stress in English. All in all, I think it’s a case of instructing and drip-feeding information to students when serious instances of intelligibility do occur and when the time is otherwise right.

References

Dauer, R.M., (2005). The Lingua Franca Core: A New Model for Pronunciation Instruction? TESOL Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Sep., 2005), pp. 543-550

Dauer, R.M., (1993). Accurate English: A Complete Course in Pronunciation, Prentice Hall Regents: USA

Fudge, E., (2016). English Word-Stress, Abingdon: Routledge

Jones, D., (1922). An Outline of English Phonetics, New York: G.E. Stechert & Co.

Kelly, G., (2000). How to Teach Pronunciation, Harlow: Pearson Education Limited

Levis, J.M., (2018). Intelligibility, Oral Communication, and the Teaching of Pronunciation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Roach, P., (1991). English Phonetics and Phonology: A practical course, Second edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Rogerson-Revell, P., (2011). English Phonology and Pronunciation Teaching, New York: Continuum International Publishing Group

Underhill, A., (2005). Sound Foundations: Learning and teaching pronunciation, Oxford: Macmillan Education