Four staggering stories and facts about European languages

Well, I’m fresh out of reading a most fascinating book that’s full of jaw-dropping facts about European languages.

The title of the book is Lingo: Around Europe in Sixty Languages, and the author is Gaston Dorren. Dorren is a Dutch linguist, journalist and polyglot.

Hence, if you’re a lover of European languages, read on to get to know some flabbergasting stories, origins and facts about European languages.

FACT 1: Finnish and Hungarian are related

Before reading Lingo, I’d always thought that the Hungarian language was in a language group all of its own.

What I naive fool I’d been all my life.

Hungarian actually belongs to the Finno-Ugric language group, meaning its nearest relatives are Finnish and Estonian.

Wishing to emphasise the relationship between Hungarian and Finnish here, it’s vital to mention that the period of separation between the Hungarians and the Finns is a very long time. Indeed, the Finno-Ugric family of peoples went their separate ways around c. 4,500 years ago.

Therefore, you’re not going to find any Finns being able to make themselves understood in their mother tongue in Budapest. Or any Hungarians in Helsinki, for that matter.

In an eye-opening short essay, Dr. Gyula Weöres, a lecturer in Hungarian at the University of Helsinki in the early twentieth century, commented on a Hungarian journalist who had visited Finland and was taken aback by how dissimilar Finnish and Hungarian were to each other.

All in all, a great deal of expertise is required to decipher a linguistic relationship between Finnish and Hungarian.

FINNISH-HUNGARIAN COGNATES AND LEXICAL SIMILARITIES

In brief, cognate words share the same origin or are related in some way.

There are around two hundred common words in Finnish and Hungarian. These are staple words required in everyday language and which describe basic concepts. This vocabulary generally refers to parts of the body, family members, elementary tools and fishing.

Naturally, 4,500 years of separation has meant that plenty of modifications have taken place between the related words. These changes have mostly been phonetic, although occasionally the entire meaning of words has changed.

A sentence typifying the linguistic similarities between the two languages goes like this:

ENG - The living fish swims underwater

FINNISH - Elävä kala ui veden alla

HUNGARIAN - Eleven hal úszkál a víz alatt

Here are some more related words:

Cognate words - English, Finnish and Hungarian

The similarities between the first six examples in the box are very clear.

I’ve included the last example (head) as it illuminates the difficulties in recognising some Finnish-Hungarian cognates. The letter f at the beginning of words in Hungarian regularly matches the Finnish p.

PHONOLOGY IN FINNISH AND HUNGARIAN

The kinship of Finnish and Hungarian is plainer to see when it comes to phonology.

First of all, the main stress in Finnish and Hungarian words is always on the first syllable.

Secondly, vowels and consonants are evenly distributed in both languages.

GRAMMATICAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN FINNISH AND HUNGARIAN

Finnish and Hungarian have at least six grammatical features in common:

- Finnish and Hungarian have more than twelve cases;

- Both languages have postpositions as opposed to prepositions;

- The two languages are fond of suffixes;

- Both languages use a suffix, rather than a verb, to express possession. Therefore, instead of saying "I have it", speakers say something like "It is on me", to give an English equivalent;

- A singular follows numerals (‘six cat’ rather than ‘six cats’);

- Both languages ignore gender to the extent where only a single word exists for ‘he’ and ‘she’ (hän in Finnish, ő in Hungarian);

FACT 2: English has a sister language - and you’ve probably never heard of it

What language is most closely related to English?

Some people might answer ‘Scots’. However, linguists debate whether Scots is just a variety of English.

The question now is - what language is mostly closely related to English and Scots?

Well, the answer is the Frisian language. Or, to be more precise, the Frisian languages.

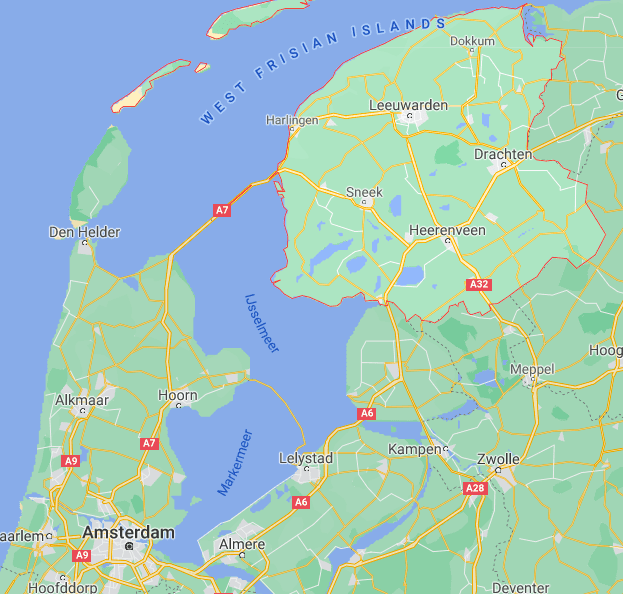

Around 500,000 people living on the southern fringes of the North Sea in the Netherlands and Germany speak Frisian.

Old English and Old Frisian were very close to each other. These days, however, the two languages are not mutually intelligible. English underwent a dramatic transformation owing to contact with other languages, such as Norman French. In contrast, the various varieties of Frisian have been heavily influenced by Germanic languages.

The three different strands of Frisian

WEST FRISIAN

West Frisian is by far the most widely spoken Frisian language.

Around 450,000 people speak West Frisian, mainly in the Dutch province of Friesland.

As you can see in the map below, Friesland is in the far north of the Netherlands. The provincial capital is Leeuwarden.

In certain parts of Friesland, between 70 and 83% of people are native speakers of Frisian.

NORTH FRISIAN

North Frisian is spoken in parts of Schleswig-Holstein - Germany’s northernmost state. Its capital city is Kiel.

Less than 10,000 people speak Northern Frisian. Hence, it’s considered endangered.

SATERLAND FRISIAN

Only a few thousand people speak the Saterland variety of Frisian.

Saterland is a municipality in the state of Lower Saxony, Germany.

Basic phrases and sentences in West Frisian

Basic phrases in West Frisian include Goeie moarn (good morning) and Tankewol (thank you). Notice the phonetic similarities to English.

Here are a few sentences:

- Dat binne har boeken - Those are her books

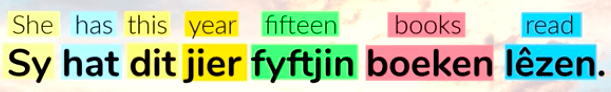

- Sy hat dit jier fyftjin boeken lêzen - She has read fifteen books this year

Analyse the phonetic similarities between English and Frisian in the second sentence with this word for word translation:

FACT 3: The Lithuanian language is closest to Proto-Indo-European (PIE) - the single tongue which all Indo-European languages descend from

By the 19th century, linguists had established that all modern Indo-European languages descended from a single tongue. This tongue is called Proto-Indo-European (PIE).

Linguists generally agree that PIE was spoken as a single language from 4500 BC to 2500 BC.

RECONSTRUCTING PIE

Unfortunately, no written texts in PIE remain. Instead, scholars have had to piece together PIE from its present-day descendants with the aid of the comparative method. This is a technique for reconstructing an earlier language through a comparison of related words and phrases in various languages or dialects which stem from this shared ancestor.

Linguists have also benefited from studying old documents in ancient languages such as Sanskrit, Greek and Latin - all descendants of PIE. Furthermore, more recent sources as diverse as Old English Beowulf (around the ninth century) and the first written traces of Albanian (fifteenth century), also have a say in the process of reconstructing PIE.

LITHUANIAN AND PIE

The general consensus among scholars is that Lithuanian is the language which has kept the majority of the features of PIE.

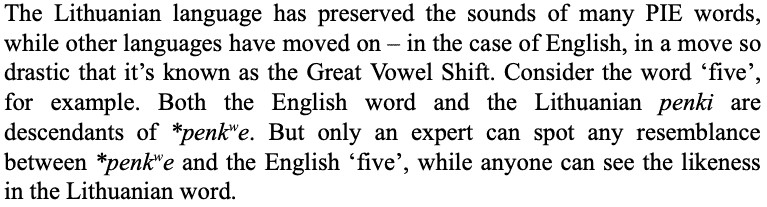

In terms of phonology, Lithuanian has maintained the sounds of many PIE words, unlike English, as Dorren notes with regard to the word ‘five’ (p.16):

Then there are the grammatical similarities between PIE and Lithuanian. For example, PIE had eight grammatical cases, while Lithuanian still has seven. Of course, there are other languages, such as Polish, which have seven cases. However, only in Lithuanian do the cases bear resemblances to those in PIE.

This revelation about Lithuanian cases takes us into the last of our startling facts about European languages.

Cases are on their way out.

FACT 4: The case system is beginning to crumble around Europe

Having learned both the Polish and Serbian languages, I’ve had to devote a reasonable amount of time to getting to grips with cases. Serbian and Polish both have seven cases.

With that in mind, I was flabbergasted to read in Lingo that cases are on their way out.

North, west and south of the German language area, there are not many cases to be had. In the northwest of Europe, only several small languages have retained them: Faroese, Scottish Gaelic, Irish Gaelic and Icelandic.

Further south, Bulgarian and Macedonian have almost completely relinquished themselves of cases. Moreover, Romanian and Greek are just about holding on to their last three or four.

East of German-speaking territories, cases are omnipresent. Nevertheless, the number of languages with fewer cases than the eight possessed by their PIE ancestor is abundant. In Central and Eastern Europe, cases “are far from dead, but the current is flowing in one direction and one direction only.” (Dorren, p.149).

I do ask myself - are cases just too complicated for people? In Czech, for example, a single word form often represents a large number of cases. Take Nádraží (‘station’), for instance, which stands for no fewer than six inflectional forms in the singular and four in the plural.

Personally, I’ve never grumbled about learning Polish and Serbian cases. It’s just the way things are. Other languages without cases have their own unique complexities as well.

To name but a few stories and facts about European languages

In this post, I’ve described four revealing stories and facts about European languages.

I encourage you to read Lingo: Around Europe in Sixty Languages to find out more as I’ve only scratched the surface here.

I could have also written about the decline of Danish over the past few centuries. Or the remarkable stability of the Icelandic language over the past 800 years. Perhaps I could have touched upon the dazzling array of diminutives and augmentatives in Italian.

Over to you then.

References:

Dorren, G. (2015). Lingo: Around Europe in Sixty Languages, Atlantic Monthly Press: New York

Jorgensen, P. (2020). FRISIAN - Sister language(s) of English!, Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MGP7N_Hdmok (Accessed: 14/5/2021)