Fossilization in second language acquisition

Fossilization in second language acquisition. Well, it’s a topic I’ve been meaning to write about for years. I’ve finally got around to it because I’ve noticed that many of my Polish students of English have reached the end of the line. Many of them have wonderfully rich vocabularies, excellent comprehension skills and the ability to speak with confidence. Unfortunately, they subconsciously cling to facets of their mother tongue. Negative language transfer - when differences between the structures in two languages structures leads to systematic errors in the learning of the second language - is rife among the majority of Polish learners of English.

In this post, I consider the origins of the notion of fossilization in second language acquisition. Furthermore, I examine why learners’ linguistic systems fossilize. I also discuss methods which I believe might help learners to overcome fossilization.

ABBREVIATIONS:

L1 - first language

L2 - second language

IL - interlanguage

THE ORIGINS OF THE NOTION OF FOSSILIZATION IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

Larry Selinker, professor of linguistics at the University of Michigan, coined the term “fossilization” in his 1972 paper Interlanguage (IL).

Nevertheless, we must still credit several linguists for sowing the seeds of Selinker’s theories. First of all, American-Polish linguist, Uriel Weinreich, is renowned for providing the foundational information which formed the basis of Selinker's research. In 1953, Weinreich made reference to “permanent grammatical influence”.

Another scholar, William Nemser, wrote about “the formation of permanent intermediate systems and subsystems” (1971:117). Essentially, these systems and subsystems are deviant grammatical and phonological structures. According to Nemser, “effective language teaching implies preventing, or postponing as long as possible” the formation of these atypical structures. Hence, on the same lines as fossilization, Nemser coined the term approximative system. This term defines the deviant linguistic system the learner employs when attempting to use the L2. These approximative systems vary in character depending on proficiency level, exposure to the target language and personal learning characteristics etc.

Stable varieties of the approximate systems Nemser referred to are typically found in immigrant speech. Many immigrants are long-time users of their L2 who, despite attaining considerable spoken competence, have reached a plateau in their learning.

Pit Corder, professor of applied linguistics at Edinburgh University, undoubtedly had an influence on Selinker’s research. In his 1967 paper, The Significance of Learner’s Errors, Corder used the term transitional competence to describe the deviancy and flux of the language learner’s evolving target language linguistic system.

WHAT IS INTERLANGUAGE ACCORDING TO sELINKER?

Out of all of the above terminology, Selinker’s term Interlanguage seems to have stood the test of time the best.

An IL is essentially an idiolect which preserves features of the learner’s mother tongue, and is likely to overgeneralise L2 speaking rules. Hence, every learner develops speech habits which are unique to them.

A learner’s IL is susceptible to 'fossilization' or a cessation in its development in any of its stages of development. Moreover, one’s IL might be shaped by transfer from the L1 to the L2, previous learning strategies, current strategies of L2 acquisition, L2 communication strategies (circumlocution) and overgeneralization of L2 language patterns.

AN EXPANSION IN THE SCOPE OF THE NOTION OF FOSSILIZATION AND AN APPROPRIATE DEFINITION OF FOSSILIZATION IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

Throughout the 1970s right up until today, the notion of fossilization has expanded significantly in scope. In 1978, Selinker and Lamendella explicitly defined fossilization as:

“ … a permanent cessation of IL learning before the learner has attained TL norms at all levels of linguistic structure and in all discourse domains in spite of the learner’s positive ability, opportunity, and motivation to learn and acculturate into target society.” (in Han, p.15)

Selinker also moved the goalposts with regard to the percentage of learners who successfully achieve second language acquisition. Initially, Selinker had claimed that 5% of language learners achieve native-like competence. Yet, in some of his papers in the 1990s, Selinker claimed that no adult learner can hope to achieve native-like ability in a second language in all contexts.

Summing up, perhaps Vanpatten and Benati (2015:119) best define fossilization:

“Fossilization is a concept that refers to the end-state of SLA, specifically to an end-state that is not native-like. By end-state, we mean that point at which the learner’s mental representation of language, developing system, or interlanguage (all are related constructs) ceases to develop.”

THE FOUR STAGES OF INTERLANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

Brown (1987: 175) presents four stages to describe learners’ efforts when it comes to acquiring the target language system:

1. Random errors or pre-systematic stage:

At this stage, the learner is hardly aware of the systematicity attached to the second language system. Hence, the learner tends to experiment with the language and produces errors at random.

2. Emergent stage:

Slowly but surely, the learner’s knowledge of the L2 increases. The learner is more aware of the rules that create the whole second language system and is able to apply them in a relatively successful manner. Nevertheless, the learner continues to make errors and cannot correct them on his/her own. Typically, the learner is in his/her comfort zone and avoids using certain structures. Finally, the phenomenon of backsliding is likely to occur.

According to Han (2004:102), backsliding is the “variational reappearance over time of interlanguage features that appear to have been eradicated.”

3. Systematic stage:

Here, the learner shows greater consistency in producing the L2. Output approximates TL norms, even though the rules are not all well-formed. Furthermore, the learner is capable of self-correction when prompted to do so by a teacher.

4. Stabilization or post-systematic stage:

At this stage, the IL form is prone to stabilization. The learner produces few instances of incorrect language, and is able to self-correct. Despite these positive traits, the learner’s linguistic system is far from native speaker competence. Unfortunately, the stabilised language is more likely to 'get stuck' rather than develop. In essence, the learning process begins to resemble a 'plateau'.

The long-term cessation of IL development - a major component of stabilization - is a state preceding fossilization. Brown (1987:176), for one, treats stabilization as a phenomenon which is the harbinger of fossilization.

HOW CAN INDIVIDUAL FOSSILIZATION BE CLASSIFIED?

According to Selinker (in Wei, 2008), individual fossilization consists of two types: error reappearance, and language competence fossilization.

Error reappearance refers to those IL structures which are presumed to have been corrected yet continue to appear regularly. This resurfacing of errors can be found in the IL of beginners or learners with low proficiency.

Contrary to error reappearance, language competence fossilization refers to the plateau in the development of L2 learners’ phonological, grammatical, lexical and pragmatic competence. Hence, L2 learners who have been learning an L2 for a long period of time, reaching a relatively high level, are subject to language competence fossilization.

Fossilization in second language acquisition can also be classified into temporary fossilization and permanent fossilization. As the terms suggest, the former is unstable and changeable, while the latter is in a state of stabilisation.

WHY DO LEARNERS’ LINGUISTIC SYSTEMS FOSSILIZE?

Now that I’ve reviewed the literature regarding fossilization in second language acquisition, let me now explain the main reasons why I think learners’ linguistic systems fossilize:

1. LANGUAGE TRANSFER AND FOSSILIZATION

In my view, fossilization mostly arises and persists due to negative language transfer. Negative transfer refers to how the influence of the L1 causes errors in the acquisition of the L2.

I have a reasonable knowledge of the phonological, morphological and syntactic patterns belonging to the Polish language. Therefore, I tend to recognise the vast majority of errors Polish learners of English make owing to language transfer.

I’ve been updating lesson notes for some students since as far back as 2014. Hence, I've noticed that error correction during and after class has little to no impact on eradicating fossilization due to negative language transfer. Moreover, I expect that most of my students read over these lesson notes between classes. Even this seems to be having little effect on neutralising fossilization.

Selinker (1972) believed that some language rules in the learner’s IL are transferred from his/her L1. Regarding Polish students, I would say that they transfer the great majority of rules from Polish to English.

2. STATE SCHOOL ENGLISH LANGUAGE SYLLABUSES WHICH AIM TO “TEACH EVERYTHING UNDER THE SUN” AND DO NOT PAY HEED TO EVENTUAL FOSSILIZATION

Unfortunately, English language teaching in Polish secondary schools is at the mercy of syllabus writers who can’t detach themselves from a linear grammatical syllabus. This is the idea that students should firstly “learn” supposedly “easy” grammatical items, such as “have got” and “There is/are”. Thereafter, tense aspects such as the present continuous and present simple are taught in the usual predictable order.

In a recent post, I outlined what I believe is a viable spoken English syllabus for secondary school students at the intermediate level. In that post, I revealed the shock I experienced when I Googled, in Polish, “program nauczania języka angielskiego” (teaching programme for the English language). Worryingly, major ELT publishers have control over the preparation of English language syllabuses for primary and secondary schools in Poland.

You’re beginning to get a feel for the root causes of fossilization, aren’t you?

Publishing houses just want to flog coursebooks. The easiest way to do that is to churn out the same old tense aspects and gap fill exercises, book after book, year after year. Frankly, publishing houses, coursebook writers, and state school English language syllabus writers are oblivious to the issues Polish students of English face, such as the ubiquitous butchery of the English preposition system.

I’ll never forget the 110-page syllabus I found for “four-year general secondary schools and five-year technical secondary schools” in Poland. There’s too much lovely terminology, methodological rambling and pen-pushing in this document. Besides, teachers have to teach to the test. I doubt that they’d be inclined to read such a syllabus in any great detail.

Well, I had a good browse of this syllabus. It seems that many syllabus writers live in their heads. All that’s important for them is short-termism. As for the fossilization and negative language transfer that 95% of Polish learners will endure as adults, syllabus writers and ELT publishers don’t need to worry. We’ll pick up the pieces for them.

3. SYLLABUSES WHICH APPROACH THE TEACHING OF TENSES AND TENSE ASPECTS IN SUCH A PREDICTABLE WAY

Fossilization results from overteaching. I rarely come across Polish students of English who have a reasonable command of the present tense aspects. On the whole, they overuse the present continuous. Unbelievably, students are taught the differences between the present simple and present continuous for almost a decade. Therefore, I can only conclude that overteaching and all those ridiculous gap-fill exercises cause cognitive overload.

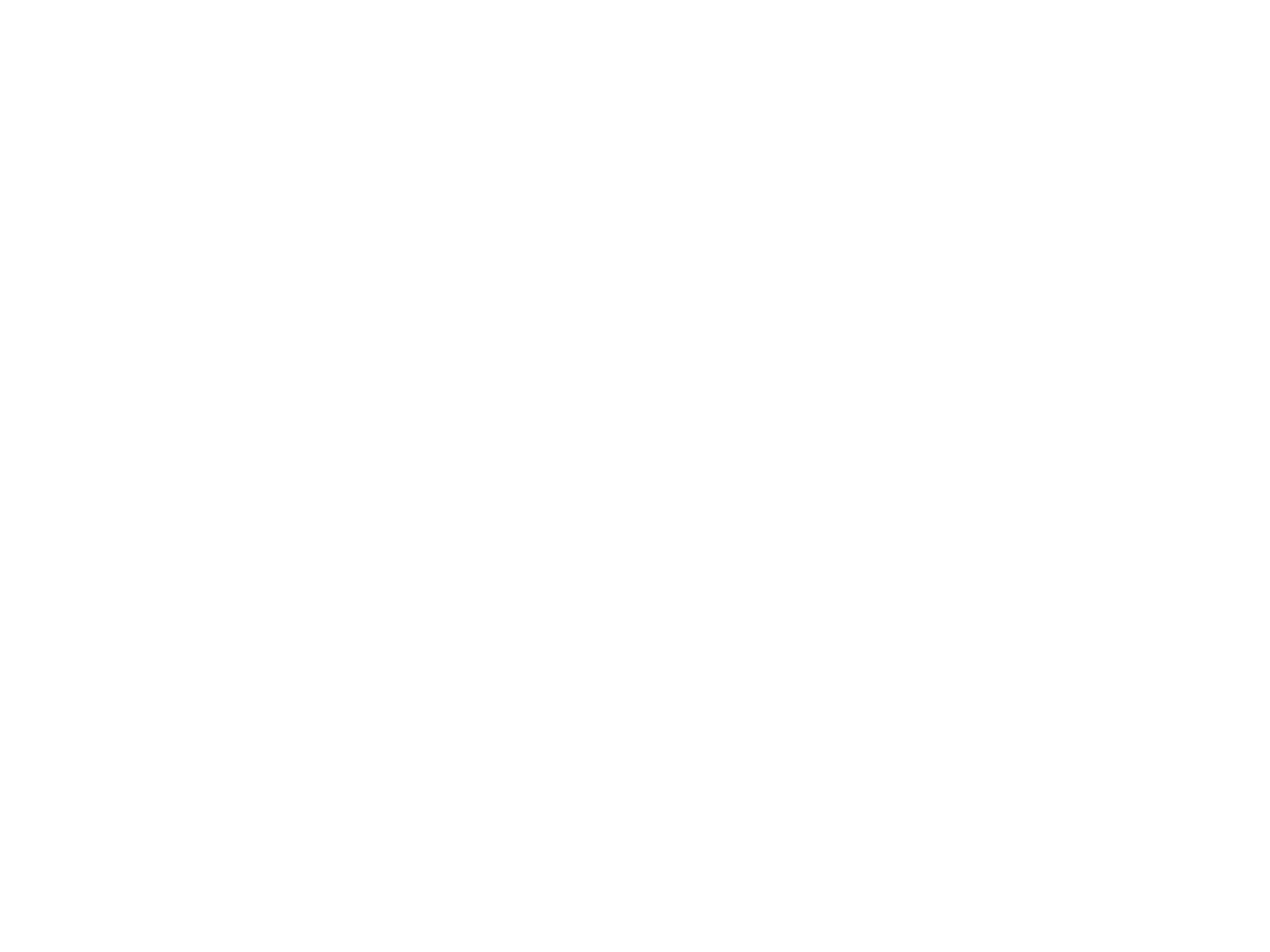

Here’s part of the grammatical syllabus from the 110-page syllabus I mentioned in the previous section:

Again, I am adamant that overteaching and unnecessary teaching sow the seeds for fossilization due to cognitive overload. Just because English aspects, such as the future perfect and future perfect continuous exist in theory, it doesn’t mean they have to be taught and compared with one another. Frankly, I can’t remember the last time I used one of these aspects in conversation. Let’s just delete these points from spoken English syllabuses.

Finally, do syllabus writers seriously believe that learners should use the passive voice in conversation? Native speakers of English hardly ever use it. Therefore, it shouldn’t be included in spoken English syllabuses at all.

Overall, teachers and syllabus writers are loath to point out to students which grammatical items are suitable for written English and which are normally used in spoken English. The result is hordes of young adults who speak much too formally. They’re simply not aware that native speakers of English use a limited range of grammatical structures in everyday conversation.

4. TEACHING STRATEGIES

Wysocka (2007:277) hits the nail on the head when she states that “learners/user’ linguistic competence … depends a great deal on teaching strategies.”

Typically, as Wysocka continues, teachers rely on “rigid lesson plans and tasks resulting in a repetitive and often patterned practice.” As a result, learners’ language behaviours become, for want of a better phrase, stuck in a rut.

Wyscoka also picks up on the point of teachers attempting to “lower the group level.” This is realised through the use of simple activities which teachers deploy to save face. If tasks are challenging with solutions that require detailed explanation, teachers might worry that their insufficient linguistic skills will be exposed.

Perhaps a bigger issue here is the fossilization, or deterioration, of the teacher’s pedagogical skills. Many English language teachers in state schools are afraid to push the boat and challenge their students with authentic materials, such as TED talks or exercises based on corpora.

5. FACTORS IN THE SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT

There are other grave issues in the school environment which can lead to fossilization.

Firstly, it might be the case that instructors themselves have not attained grammatical mastery of the L2. Therefore, they inevitably guide their students into incorrect usage. I wouldn’t like to tar all Polish teachers of English working in state schools with the same brush. However, I’ve met a fair few with suspect levels of English.

The issue of weaker teachers and students’ exposure to inaccurate patterns is especially exacerbated if they do not make extensive use of authentic models (via film and video etc.)

Secondly, there are those instructors who prefer not to correct their students’ mistakes. This might be for “philosophical, methodological, or personal reasons.” (Higgs and Clifford, in Valette, p.326).

Finally, as Valette points out (p.327): “the classroom situation provides large quantities of comprehensible but flawed input in the form of highly motivating but highly inaccurate peer speech.”

Frankly, I never did get my CELTA trainers who insisted on students chatting in small groups while the teacher would 'monitor' proceedings (prance around the classroom) and pretend to listen. Overall, I believe that students acquire inaccurate forms that their peers produce.

6. THE INCORRECT APPLICATION OF LEARNING STRATEGIES

Equally as serious as negative language transfer, in my view, is the learner’s incorrect application of learning strategies.

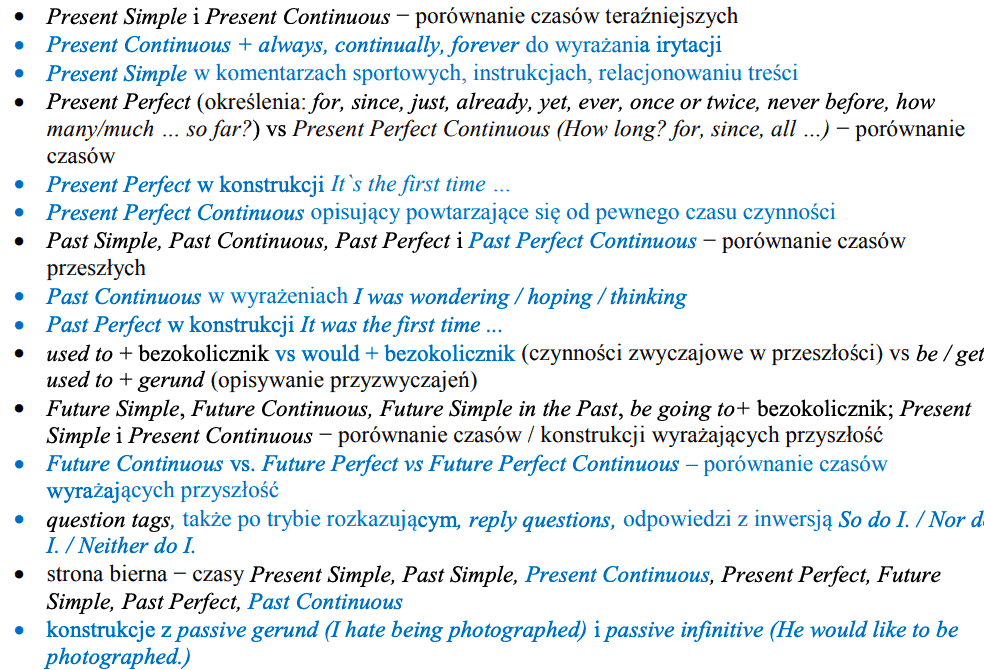

Here are three mistakes, with corrections, that one of my learner’s recently made in a class.

The majority of learners might assume that recalling the correct versions in the immediate future should mean that the mistakes have been permanently dealt with. Of course, this is not the case. Reading through lesson notes from time to time does not count as a language learning strategy.

7. THE ACCULTURATION/PIDGINISATION APPROACH

Towell and Hawkins (1994) write about ‘The Acculturation/Pidginisation Hypothesis’. According to the authors, the main focus of this approach is “the incompleteness in ultimate attainment of knowledge of the L2, and individual differences between learners in their levels of ultimate attainment.” (pp.37-38).

The cause of such 'incompleteness' lies in the social distance between the learner and the native speakers of the L2. Essentially, the larger the social distance, the more rudimentary the learner’s IL will be. This is where the term ‘pidgin English’ comes into play. Someone with ‘pidgin English’ lacks morphological inflections, subordinate clauses and auxiliaries, and so on.

According to Towell and Hawkins, if the distance between the learner and L2 native speakers fails to decrease, the L2 learner’s grammar will fossilise.

8. THE SATISFACTION OF COMMUNICATIVE NEEDS

Han (2004) mentions researchers who have considered ‘satisfaction of communicative needs’ as a major causal factor of fossilization. One such scholar was Klein (1986, in Han, 2004) who speculated that some L2 learners are aware of the fossilised deviances in their IL. Nevertheless, they’re not inclined to restructure them as their fossilised varieties can fulfil their basic communicative needs.

I've written about the intermediate plateau on this blog. Essentially, it gets harder and harder at the top end of the intermediate scale to improve. Elementary level learners notice quick improvements. However, there’s much less knowledge available for those learners who hover around the upper-intermediate level. Hence, progress comes to a virtual halt. The reason I’ve mentioned this is because those learners who succumb to the intermediate plateau might use ‘the satisfaction of communication needs’ as an excuse to avoid putting in extra effort to overcome the intermediate plateau.

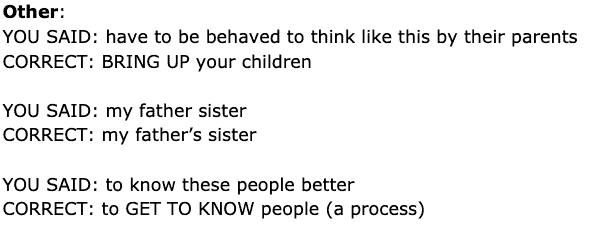

9. TEACHERS OVERLOOK ORAL INDICATORS OF FOSSILIZATION WHICH ARE NOT RELATED TO SYNTAX, TENSE ASPECTS AND MORPHOLOGY

Fossilization is not only related to grammar mistakes and mixing up tense aspects.

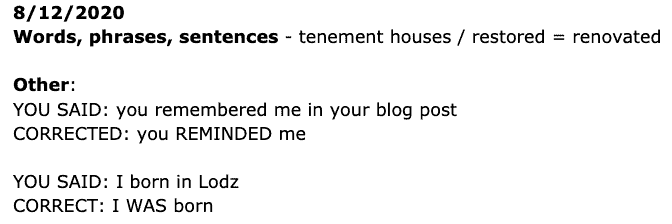

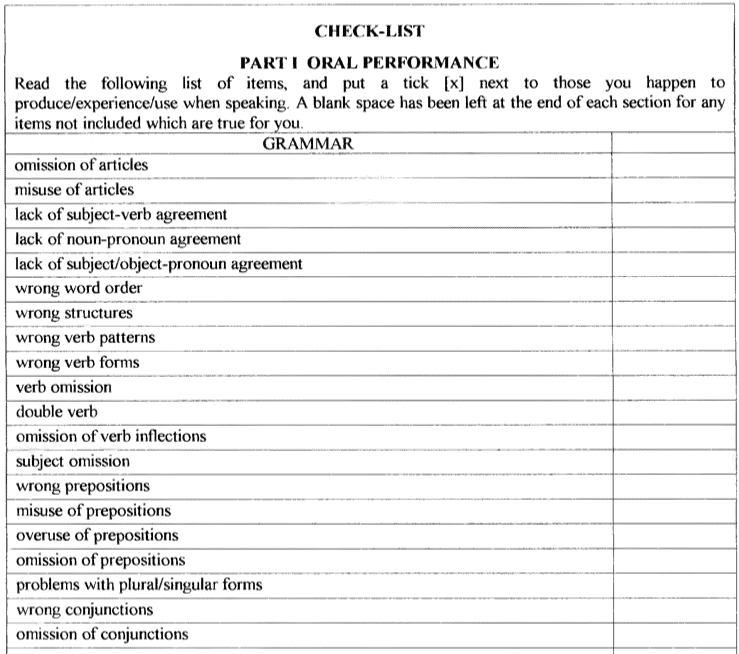

As the list below indicates (Wysocka, p.62), there are plenty of non-grammatical oral indicators of fossilization. These include false starts, fillers such as ‘you know’, ‘like’ and ‘uh’, and the overuse of discourse markers:

If the learner demonstrates any of these oral indicators of fossilization, the teacher should not feel ashamed to point them out.

WHICH STRATEGIES CAN TEACHERS AND LEARNERS EMPLOY TO PREVENT AND REVERSE FOSSILIZATION IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION?

I’ll now analyse some of the strategies which I believe teachers and learners could employ to prevent and reverse fossilisation in second language acquisition.

THE ROLE OF THE TEACHER

1. ‘ORDERLINESS OF INPUT’

In his book Errors in Language Learning and Use: Exploring Error Analysis (2013), Carl James makes a great point about the ‘orderliness of input’. In order to prevent learners’ linguistic systems from fossilizing, the teacher should ensure that “newly taught items are repeated a lot, and are spaced away from other TL forms that are similar.” (p.241).

This point reminds me of most syllabus writers’ and teachers’ obsession with teaching the present simple and present continuous aspects in conjunction with one another. As I argued in this post, most Polish learners of English have little control over these two aspects. The most concerning issue is their overuse of the present continuous. Frankly, I’d do away with teaching the present continuous because it’s hardly used in everyday conversation. If teachers are not up for this idea, they should significantly extend the period of time between the teaching of the present simple and present continuous so as to avoid overloading their students.

2. TEACH A ‘LITTLE LANGUAGE’

James also mentions the idea of reducing a syllabus. In other words, teachers could do with teaching a ‘little language’ - a mini-version of the native speakers’ TL (p.241).

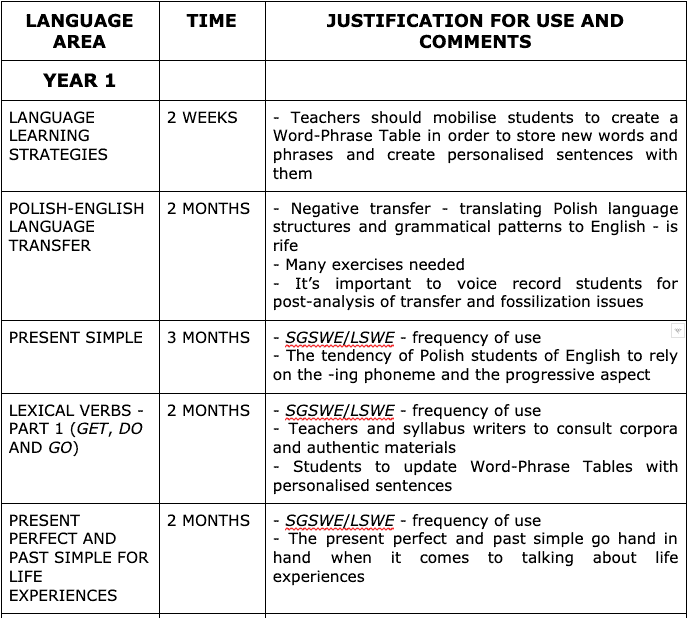

When I proposed a spoken English syllabus for intermediate learners in Polish secondary schools, I did so with minimalism in mind:

As you can see above, there isn’t a glut of tenses and aspects. Logic tells me that for every unnecessary structure a teacher introduces to students, the chance of fossilisation rises with every structure.

I also argue that a syllabus should be tailored to the particular linguistic issues a certain nationality suffers with the most. For instance, Polish students overuse the present continuous when they should use the more common present simple. Moreover, many Polish learners of English rely solely on the present perfect for talking about life experiences. In fact, it is the past simple which provides specific details about life experiences.

HOW CAN THE LANGUAGE LEARNER ASSUME RESPONSIBILITY TO TURN THE TIDE AGAINST FOSSILIZATION?

1. VOICE RECORDING

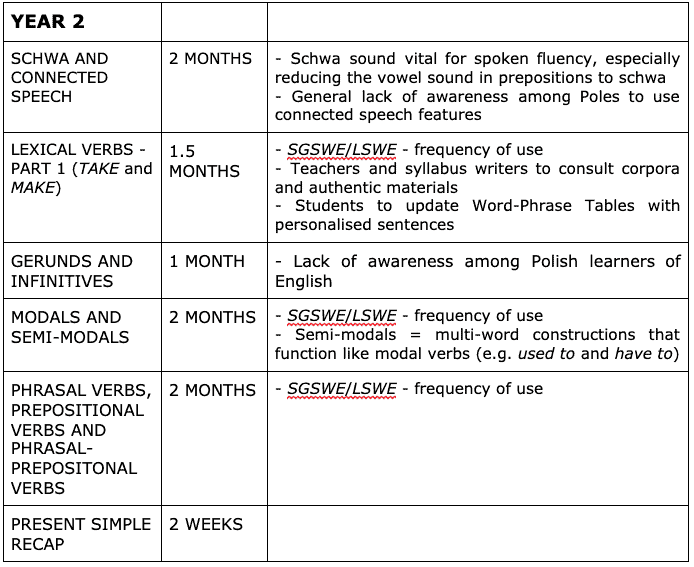

The set of notes below are from a recent class I had with a Polish student.

The second mistake I highlighted in the notes (I born in Lodz) is a fossilised error for this learner. Over the years, perhaps I’ve been guilty of encouraging this vicious cycle:

STUDENT MAKES AN ERROR → TEACHER CORRECTION AFTER CLASS → HOPE THAT THE ERROR WON’T OCCUR AGAIN → STUDENT MAKES THE SAME ERROR AGAIN IN THE NEAR FUTURE

I can only recall a few learners who’ve truly been able to repair a significant majority of their fossilised errors through MY after-class correction sessions and revising lesson notes.

Lately, I’ve been getting my students to sound record two-minute samples of their speech. Getting learners to engage in voice recording is one way to help them become more autonomous. By recording their own voices, transcribing the content and taking part in retrospective self-correction, students get closer to the real nature of their IL. Hence, if students begin to self-correct and 'think in English' between classes, they may be able to do it while speaking the language.

One student of mine, Miki, has already shared a few recordings with me. The evidence suggests that he’s already corrected large parts of his intonation system after only three recordings. It’s too early to say whether he can remedy some of those fossilised grammatical errors. However, during our most recent session, I praised him for using the present simple whereas, beforehand, he mostly used the present continuous.

2. KEEP A CHECK-LIST

As an extension to transcribing voice recordings, students can self-diagnose their errors and foster their awareness of fossilization via an oral performance check-list.

Here’s part of a check-list of language items which Wysocka provided in her work (p.271):

3. ADOPT A HIGH-QUALITY LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGY AND STICK TO IT

I’ve written extensively on this blog about the benefits of keeping a Word-Phrase Table. In my view, there’s no better language learning strategy to mentally internalise lexis and grammar structures.

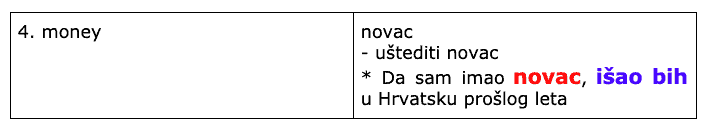

When I started learning Serbian, I didn’t get bogged down with cases and grammar rules. My learning was very much anti-structuralist and incidental. For example, I came across the equivalent of the English third conditional in my first few months of learning:

Hence, it was simple enough to memorise the L2 word for money. The next step is to use the teacher as a precious resource to provide useful collocations to add to the table. After the dash, uštediti novac means to ‘save money’.

The key part of the table is the TRUE personalised sentence after a star (*):

Da sam imao novac, išao bih u Hrvatsku prošlog leta

(If I had had enough money, I would have gone to Croatia last summer).

If language learners fill their tables with TRUE sentences about their life experiences, current situation (work and personal) and people they know etc, regular revision will allow them to recall the sentences in future conversations.

It’s irrelevant that I was dabbling with such conditional sentences so early in my learning. There are no rules to say that a language learner must practise the present tense for a whole year.

As you can see, visualisation should play a huge role in a Word-Phrase Table. Blue and red are two colours which appear in the Croatian flag. Such colourful associations aid memory retrieval.

As my vocabulary continued to broaden, this one model sentence helped me to produce other third conditional sentences in future conversations. There is no chance that this structure will turn into a fossilized error because I’m still mentally tuned into my Word-Phrase Table seven years down the line.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS - dECLARING WAR ON FOSSILIZATION IN SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

All in all, hope is not lost for teachers and learners seeking to stamp out fossilization.

Quite frankly, I haven’t got time for linguists who claim that adult learners cannot overcome fossilization. They often back up their claims with one or two extreme examples of learners who couldn’t overcome their difficulties with English, despite living in countries like the UK and the USA for many years. The case of renowned physicist, Professor Chien-Shiung Wu, who arrived in the U.S. in 1936 at the age of 24 and had since lived and worked there until her death at 83, would be a case in point. Wu had 56 years of exposure to English as her L2. Nevertheless, she was unable to overcome all of her early difficulties with the language.

I admit that Wu’s case is very surprising. However, she no doubt had other things on her mind, such as nuclear physics, to worry about achieving native-like competence. Hence, learner motivation is unquestionably linked to fossilization.

It’s not all doom and gloom in the world of research into fossilization. There are also scholars, such as White and Genesee (1996, in Han, 2004), who have come to the conclusion that it is possible for adult L2 learners to acquire native-like competence.

In my view, there are teaching strategies, learning strategies and spoken English syllabuses which can help to neutralise fossilization.

Fossilization in second language acquisition exists because so few have decided to declare war on it.

References

Brown, H. D. (1987). Principles of language learning, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Corder, S.P. (1967). ‘The Significance of Learner's Errors’, IRAL, 5/4 NOV, 161-170

Han, Z. (2004). Fossilization in Adult Second Language Acquisition, Multilingual Matters: UK

James, C. (2013). Errors in Language Learning and Use: Exploring Error Analysis, Routledge: Oxon

Nemser, W. (1971). Approximative Systems of Foreign Language Learners, IRAL, 9/2 MAY, 115-123

Selinker, L. (1972). ‘Interlanguage’, IRAL, 10/3 AUG, 209-241

Towell, R., and Hawkins, R. (1994). Approaches to Second Language Acquisition, Multilingual Matters: UK

Valette, R.M. (1991). ‘Proficiency and the Prevention of Fossilization - An Editorial’, The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 75, No. 3 (Autumn, 1991), pp. 325-328

Vanpatten, B., and Benati, A.G. (2015). Key Terms in Second Language Acquisition, Second Edition, Bloomsbury Academic: London

Wei, X. (2008). ‘Implication of IL Fossilization in Second Language Acquisition’, English Language Teaching, 1/1, JUNE, 127-131

Weinreich, U. (1953). Languages in Contact: Findings and problems, Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York: New York

Wysocka, M.S. (2007). Stages of fossilization in advanced learners and users of English : a longitudinal diagnostic study. T. 1. Praca doktorska. Katowice : Uniwersytet Śląski