How to progress from intermediate to advanced English

This time around, I attempt to tackle one of the thorniest subjects in English language learning. This issue is - how to move from intermediate to advanced English.

Now, do any of the following statements describe you?:

1. You worry that you don’t incorporate enough of the new vocabulary and collocations you learn into your speech;

2. When you speak, you directly translate everything from the L1 to the L2;

3. You worry that you need to study grammar, grammar and more grammar.

Well, if these statements describe you, it’s not all doom and gloom!

Despite the hurdles, it’s definitely possible to make that shift from intermediate to advanced English. That’s the good news.

The bad news is - you’ve hit the proverbial brick wall. This barrier is called a 'language-learning plateau'.

If you're at the 'intermediate plateau', your English is good enough for people to understand you. Moreover, you’re able to understand others well enough in most contexts. However, you still feel there’s something missing. No matter what you do, it feels impossible to boost your fluency or talk about more sophisticated topics.

Back to the Start - Classroom-based Language Training

To understand why many English language learners can’t break out of the intermediate plateau, we need to look at the origins of the problem.

How can I describe foreign language classes at school?

Soul-destroying. Monotonous. Lifeless. The list could go on.

In my first post on this blog, I stressed that too many curriculum designers and teachers don’t know how to break free from a linear grammatical syllabus. A linear grammatical syllabus deludedly suggests that the learning of English should begin with the verb ‘be’. The present simple and present continuous aspects follow thereafter, and - you know the rest.

Overloading students with so many tenses and aspects gives them a phobia of making mistakes. The worst thing is - you don't need to learn most of these aspects. In conversation, native speakers of English rarely use aspects like the future perfect and past perfect continuous. Quite frankly, many native speakers have never used these aspects in their lives because they're much too formal.

Hence, what we have is a situation whereby teachers overburden pupils with obscure aspects and the passive voice. Unfortunately, many of these aspects are suitable for written English. Few teachers of English actually realise this.

The net result of curriculum designers’ and teachers’ fascination with the grammatical syllabus and gap-fill exercises is hordes of teenagers stuck at a low intermediate level.

After so many years at school, they have a limited range of vocabulary and a confused brain full of pointless tenses and aspects.

They know next to nothing about the value of learning collocations, for example.

Through not much fault of their own, the vast majority of teenagers hit a brick wall - the 'intermediate plateau'.

Unfortunately, so few of them make that leap from intermediate to advanced English AS ADULTS.

Building up to the Intermediate Plateau

We’re building up to why there isn’t usually a smooth progression as the language learner climbs the language proficiency ladder.

At the beginning, language acquisition is a rapid affair. Early on, the learner picks up a substantial amount of high frequency vocabulary. These high frequency words crop up again and again in coursebook texts and listening activities. Hence, the swift acquisition of high frequency vocabulary and basic communication ensues.

Professor Jack C. Richards wrote in his essay, Moving beyond the Plateau, that language learners who have experienced the transition from absolute beginner to real users of the language, recall the “feelings of satisfaction and achievement that comes with it and the learner finds he or she is actually capable of real communication in English.” (p.1).

Lower intermediate level learners who've got the feel-good factor

Teaching English to my wife with the aid of the excellent Innovations Elementary coursebook, I can see that she’s got the feel-good factor.

There’s a big difference between being able to say “Good morning” and “My name is …”, as a beginner, and lexically and grammatically richer sentences such as “I’ve been living in Poland since February”, which she can now do.

She can understand almost all of the questions I put to her, and is able to answer with consistent accuracy. Moreover, she’s acquired a decent supply of essential vocabulary, phrases and sentences which she can use to talk about her life experiences and current situation. All in all, she reached the lower intermediate level very quickly.

Of course, it helps that her teacher is experienced and has acquired a few languages himself. Perhaps I shouldn’t get too far ahead of myself and blow my own trumpet. The hardest part is yet to come. It takes a lot of expertise and clever psychology for a teacher to guide learners beyond the intermediate plateau.

I can’t say that I’ve led every student out of the mire that is the intermediate plateau. After all, the bulk of language acquisition takes place outside of class time. Therefore, it’s crucial that learners find which language learning strategies work best for them. I cannot underestimate how vital it is for the learner to have a system in place to store and revise new language.

The Intermediate Plateau - Accept the logarithmic scale and reject the idea of linear progress

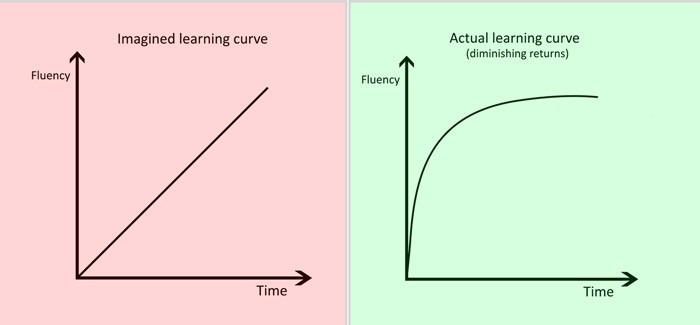

I’m grateful to polyglot Luca Lampariello for this image. It really does paint a thousand words:

Too many language learners believe that if it takes them a year to move from elementary level to a solid intermediate level, then it should take them the same amount of time to move from intermediate to advanced English. This is the imagined learning curve.

Of course, this linear-based mindset is fanciful.

As productivity author Scott Young states: “The improvement of skills works on a so-called logarithmic scale as opposed to linear”. In other words, as you improve, it gets tougher and tougher to get even better. Quick improvements come at the start, but continuing progress is much harder to come by.

As you get close to the upper-intermediate level, there’s much less knowledge out there for you to absorb. Moreover, you have to spend a great deal of time reinforcing previously learned language and rules. As you pass the B2 level, progress slows to a virtual crawl. At this point, you have succumbed to what is known as the 'intermediate plateau'.

What are the defining traits of learners who are stuck at the intermediate plateau?

Before I discuss how to become an advanced English speaker, let’s dive into the traits and mistakes of learners who can’t overcome the intermediate plateau.

1. Most learners feel right at home in their comfort zones

Think about this question real hard - is your goal in life to be great, or is it to avoid sticky, uncomfortable situations?

If you’ve been stuck on the intermediate plateau for umpteen years, you probably just want to have it easy. You’ve convinced yourself that your level is good enough. “Good enough” doesn’t exist for me. I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t try to be a better version of myself every day - in whatever it is I do.

Sure, we’re all busy. Work. Kids. Duties. However, everyone can find twenty minutes a day to immerse themselves in a language.

Going from intermediate to advanced English requires you to step out of your comfort zone and set clear goals for the rocky road ahead.

2. A lack of concrete goals

The vast majority of those who can’t get over the intermediate plateau are what I call "plodders”.

They turn up for classes and do their homework. However, they lack sufficient enthusiasm to make that transition from intermediate to advanced English.

In a nutshell, these plodders lack goals!

3. There is a noticeable gap between receptive and productive ability

The learner’s listening comprehension and reading skills may have come on in leaps and bounds. Unfortunately, the level of the learner's speaking skills seems to be much lower than their receptive skills.

4. Language errors have become fossilised

Fossilisation refers to the process in which errors become a habit and cannot be easily eliminated.

The upper intermediate level learner may be very communicative and have a reasonably rich vocabulary. However, they continue to make both pronunciation and grammar errors which lower level learners might typically make. These errors continue to crop up regardless of the amount of effort and time dedicated to correcting them.

As I have discovered in recent years, teachers feel helpless in situations where the learner continues to make the same errors.

I have many communicative, eager and committed Polish learners of English. Honestly, it’s always been a pleasure to teach them. As I have a reasonable knowledge of Polish, I tend to recognise the errors Polish learners of English make as a result of negative language transfer. Negative language transfer, or negative language interference, occurs when differences between the structures of two languages cause systematic errors in the learning of the L2. Sadly, many of these errors have become fossilised. Drawing the learner’s attention to these fossilised errors after class, or correcting them while they are speaking, are fruitless tactics when it comes to cutting the errors out for good.

While it’s true that fossilised errors generally don't affect the listener’s comprehension of a message, this is no excuse for the teacher to sit back and relax, and let the errors keep rolling in. Worryingly, the learner may not even be aware of his or her fossilised errors. Hence, the teacher has to step in.

Aside from straightforward error correction after class, there are other methods available to tackle fossilisation. I shall discuss these in the next section.

5. The fluency is there but the complexity is not

It’s one thing being fluent and using well-known and simplistic language forms with ease. However, it’s totally another thing for the learner to make conscious strides to acquire new linguistic forms to make his or her language appear more sophisticated.

Richards argues that for the learner’s linguistic system “to take on new and more complex linguistic items, the restructuring or reorganisation of mental representations is required, as well as opportunities to practice these new forms.” (p.8).

Food for thought indeed.

While the teacher can provide opportunities for learners to practise new structures, I’m more interested in the mental processing that’s required to acquire complex linguistic forms. I think that EFL teachers have no idea how complicated it is for a learner to acquire and begin to use linguistic forms such as the present perfect aspect or the preposition + gerund combination. Role-play tasks, gap-fill exercises and a few discussions will not help the matter.

6. The learner is held back by a limited vocabulary range

In terms of vocabulary range, researchers claim that those on the intermediate plateau are stuck at the 3000 word level (Richards, p.12).

I think the number of words is irrelevant. What is relevant is that those who reach a plateau of learning regarding vocabulary tend to rely on lower level lexis. Moreover, they fail to recognise the importance of collocation.

Learners and teachers should both recognise that “knowing a word” involves a great deal more than the standard dictionary definition. For example, a word can have synonyms, associated chunks of language (collocations, idioms etc), different word forms, homophones, homonyms and also be polysemic. The list goes on.

7. Connected speech, contractions and schwa are non-existent

English language teachers need to recognise that failing to introduce aspects of connected speech to students will impede their fluency in the long run.

Moreover, many curriculum designers and teachers are fascinated with full forms (I have instead of I’ve). Using full forms is wholly unnatural in spoken English.

Finally, there is the schwa sound. The schwa sound is not just a regular phoneme. In fact, it is actually one of the keys to fluency. For instance, the vowel sounds in prepositions are reduced to schwa. In natural speech, words like to and for are not usually pronounced as /tuː/ and /fɔːr/, but /tə/ and /fə/.

Focus - How to go from Intermediate to Advanced English

Now it’s time to pay heed to the methods and mentality required to take your English to the next level.

1. Sack the comfort zone and WRITE DOWN some realistic goals

No, your English is not good enough. It can always be better. I don’t believe in 'good enough'.

You need to stop plodding. Plodders turn up for every class in the hope that linear progress automatically follows. This is deluded thinking. You need to start writing down some realistic goals.

It’s no good just having wildly ambitious goals in your mind. You need to write down these goals to boost your motivation and gain a sense of direction.

These goals don’t have to be too radical. For example, “I will create TEN personalised sentences using new words and phrases per week” would be very manageable.

Conversely, “I will listen to TED talks for two hours a day”, or “I will learn 50 new words a day”, are both quite unrealistic.

The following points should help you to write down three or four goals.

2. Go to war with the fossilised errors

I believe that the teacher and learner can join forces and create a plan to neutralise fossilisation.

'War' is an appropriate word because my experience tells me that in-class and post-class error correction does not help. Moreover, gap-fill exercises are not a long-term solution for dealing with fossilisation

I honestly believe that fossilisation can occur in accuracy-based environments and in the communicative classroom.

Visual and numeric associations

The learner needs to create deeper visual and numeric associations with sticky grammar points and fossilised errors.

I have several students who mix up the present perfect and past simple aspects. I recently wrote a post about this issue, so let’s recap:

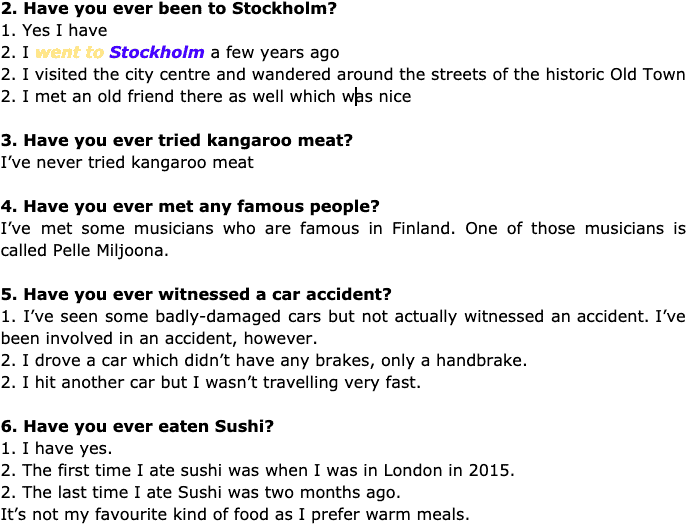

The notes above relate to a Finnish student of mine. As you can see, the main goal was to talk about life experiences using the present perfect and past simple aspects. I assumed that nobody had ever explained to him how the two aspects are used in conjunction with each other to describe life experiences. Hence, he’s hardly to blame for fossilisation regarding this language point.

The key point is that we attacked the fossilisation visually, numerically and via personalisation.

Using the colours of the Swedish flag, I highlighted went to and Stockholm. It is anticipated that the visual effect of the colour would help this learner not only to memorise the past simple in this particular context, but when talking about other life experiences using the past simple as well.

The next question is - why should we use numbers to assist with deeper mental processing and language acquisition?

In response to the question: “Have you ever been to Stockholm?”, there’s not much work to do with the present perfect. The answers “yes”, “yes I have” and “I have” are all sufficient. Therefore, the number 1 can be used to deal with the present perfect.

Thereafter, the learner should go into details using the past simple. All of these details can follow the number 2.

I thoroughly believe that the use of numbers can help this student to assemble his thoughts and apply the present perfect and past simple correctly when sharing his life experiences in future conversations.

Can the learner “notice” fossilised errors in his or her speech?

The idea of learners becoming “active monitors of their own language production”, via listening or viewing recordings of their own speech, has interested me for a while (Richards, p.20).

One of the dream scenarios for teachers who hold classes with individual students goes as follows:

(a) The learner and teacher brainstorm a full list of the learner’s fossilised errors based on previous lesson notes. This can serve as a useful reference point when it comes to comparing future errors with those existing permanent fossilised errors

(b) It is important to tap into the learner’s hobbies and passions. Therefore, the teacher can send a text to the learner a few days before class. Ideally, this text should relate to the learner’s interests. The aim is to get the learner talking in as much detail as possible

(c) Voice record the entire session

(d) The learner should write out a transcript of their speech on a Google Doc

(e) Based on the transcript, the student should highlight instances of possible fossilisation. The learner could use the comment boxes to write the correct forms

(f) The teacher can check the transcript for possible fossilised forms, and the learner's corrections in the comments boxes

(g) This exercise can be repeated at least once a month

The old sticky note routine

It’s not feasible for a learner to focus on avoiding a large number of fossilised forms in a single class.

Therefore, I have recommended my online students to attach sticky notes to their laptops which remind them of ONE or TWO of their fossilised errors. These notes serve to remind them of the fossilised error/s when they are speaking. For instance, many of my Polish students overuse the present continuous aspect. Hence, they could write the following on a sticky note:

DON’T USE THE PRESENT CONTINUOUS TODAY FOR HABITS AND PERMANENT SITUATIONS!

3. Personalisation is King

I’ve written about personalisation and Word-Phrase tables extensively on this site so I’ll keep this short.

When I learned Serbian, I broke out of the intermediate plateau when I started to add personalised sentences to my Word-Phrase Table.

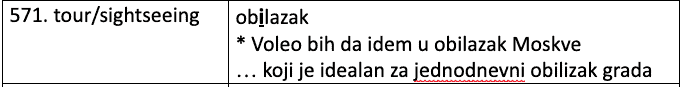

In the sample from my table above, the target chunk is sightseeing tour. My personalised sentence means “I’d like to go on a sightseeing tour around Moscow”. Of course, I’d like to realise this dream one day.

Regular revision and silent reading of these personalised sentences ensures that they’re 'swimming in the brain' during conversation. In addition to target words, I believe that personalised sentences can pass into one's long-term memory.

It’s also worth mentioning that the learner can pick up any structures which surround a target word. The personalised sentence in the table enabled me to apply the use of the Serbian genitive case (obilazak Moskve) and the use of “I’d like to” ("Voleo bih da ...") in a range of other contexts when I spoke Serbian. Five years down the line, I’m able to recall and use such structures with ease.

4. “Knowing a word” involves a great deal more than recognising the meaning of it

Most language learners only use a bilingual dictionary when they meet a new word.

Polish learners of English - don’t get me wrong. Diki is very useful. For each word, Diki tends to have:

- the recorded pronunciation of the target word;

- example sentences containing the target word;

- a range of collocations containing the target word.

A solid start. However, a bilingual dictionary won't enable you to fully get to “know a word”. From intermediate upwards, you need to be using English-only dictionaries.

Let’s dive into what a monolingual dictionary can offer the English language learner.

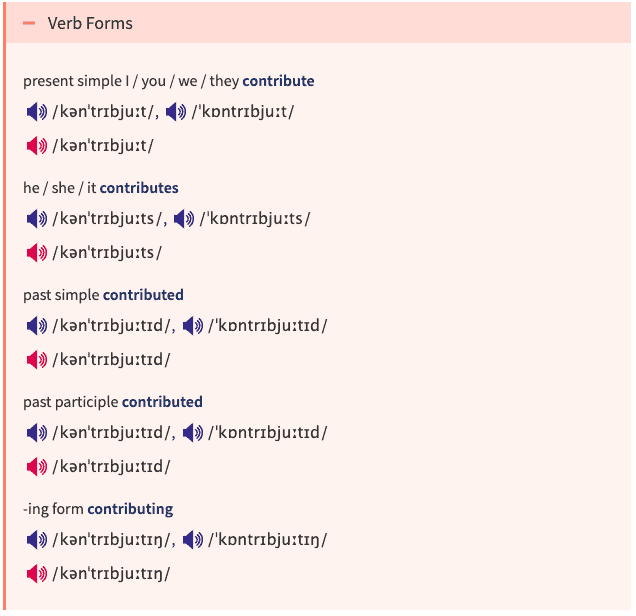

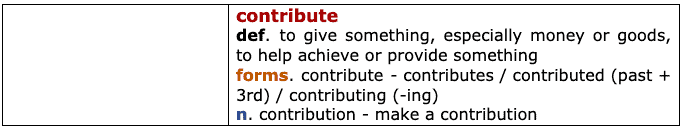

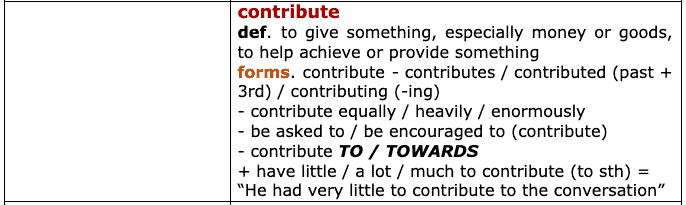

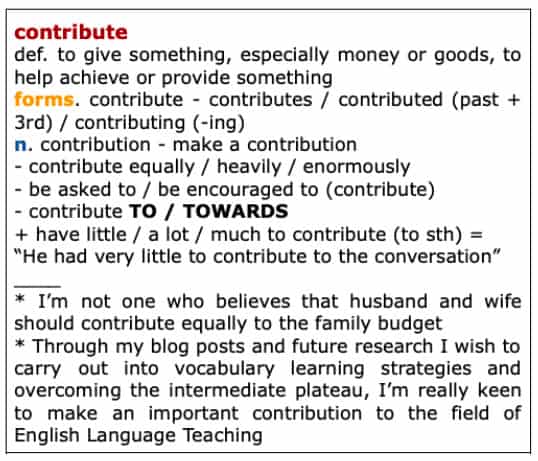

For the word contribute, I have referred to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary and the Free Online Oxford Collocation Dictionary for Advanced English Learners.

Having found a suitable definition of contribute, let’s get into the word's various verb forms, and add the noun form:

Now I’ve put myself in the learner’s shoes, I have added the verb forms and noun form (with an extra collocation - make a contribution) to a Word-Phrase Table:

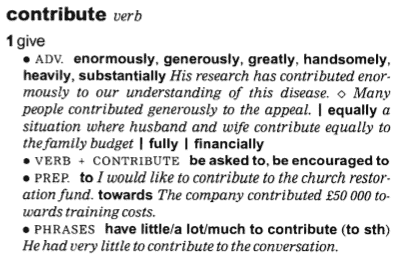

Now I want to see which adverbs, verb patterns, prepositions and phrases co-exist with the word contribute. In essence, I wish to get into collocation.

Collocation indicates restrictions on how words can be used together, such as which prepositions are used with particular verbs, or which verbs and nouns join together. The Oxford Collocations Dictionary can help me out:

Here comes the updated Word-Phrase Table with collocational information:

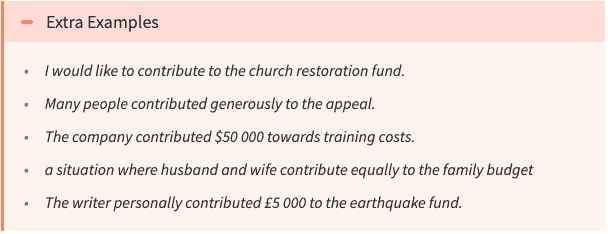

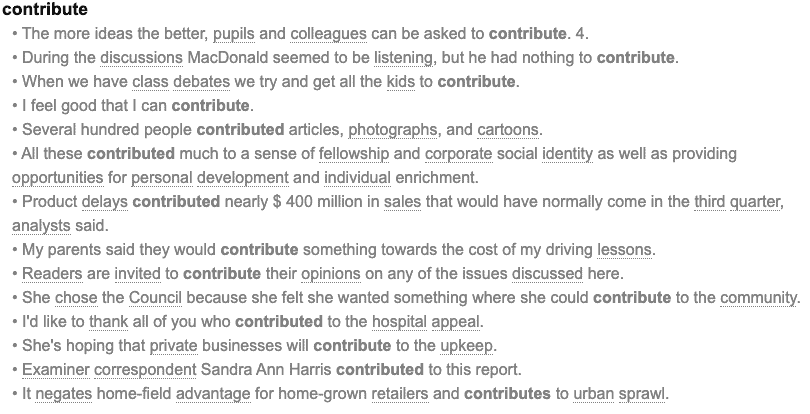

Now you can focus your attention on the example sentences containing the target word in these monolingual dictionaries. First of all, from Oxford Learner’s:

And in Longman Online:

These sentences can give you ideas and act as models to create your own PERSONALISED sentences. You can put these sentences after a star (*):

Overall, 'knowing a word' entails more than looking up a definition in a bilingual dictionary.

5. Seek out high-quality and challenging materials and immerse yourselves in them

In my last post, I wrote about five lexically rich online resources which intermediate students of English should make use of.

I won’t repeat everything again. Just to add that total immersion involves reading and rereading articles and TED talk transcripts. Of course, you should listen to TED talks as well. Refrain from reaching for your bilingual dictionary to check the meanings of new words and phrases. Try to guess meanings from context.

Printing articles and transcripts allows you to underline whole sentences which you agree with or describe your life circumstances. Alternatively, you may create personalised sentences which contain words and phrases from an article. Add all of these sentences to your Word-Phrase Table.

6. Have regular contact with English - but don’t overdo it

It doesn’t have to cost you an arm and a leg to have speaking practice with a teacher every day, or every second day.

Students who have made the most progress with me tend to have short lessons every day or every second day. These lessons tend to last between fifteen and twenty minutes.

Why have they made such scintillating progress?

Well, English has become a habit for them.

They have some contact with English every day. For instance, they may revisit their notes, prepare for the next class or actually have a class.

There’s absolutely no need to have one or two ninety-minute classes per week. I believe that a language should be broken down into bite-sized chunks. The teacher can go over some of the recently learned vocabulary, collocations and structures every class in less than five minutes.

All in all, the teacher’s aim should be to create a highly effective and consistent learning cycle.

7. Aim for natural English

The English language teacher is faced with a very complex task when it comes to helping learners embed contractions, schwa and linking devices into free-flowing speech.

Native speakers of English use contractions (They’re instead of they are and I’m instead of I am) to emphasise the main message of their utterance. The aim is for the verbs, adjectives and nouns to be heard - not grammar words like are, am and is.

As I’ve noticed with my own students, it’s difficult for them to 'de-fossilise' - to begin to use contracted forms when they’ve always used full forms. I suspect that they need to listen to plenty of real-life conversations with the SOLE PURPOSE of listening for contractions. Indeed, the learner needs to start 'noticing' features of natural English when they listen to material.

One of the reasons the learner has problems comprehending native speakers is due to schwa. The vowel sound in prepositions is rarely pronounced in its full form. Instead, native speakers pronounce for and to as /fə/ and /tə/. The schwa sound in prepositions and other short function words is hardly noticeable for some learners. Again, lots of deliberate listening practice and work with transcripts is required for students to adapt to schwa.

Finally, native speakers of English link words. The learner can sound too robotic if they don't employ linking mechanisms. One such linking device is intrusion. This means an additional sound appears between two other sounds. The /j/ or /w/ or /r/ sound can be heard between a vowel sound at the end of a word and a vowel at the start of the following word. For instance, “He asked” sounds more like “Heyasked”.

Conclusion - From intermediate to advanced English

When it comes to progressing from intermediate to advanced English, several key themes have emerged in this post.

I think that the idea of stepping out of one’s comfort zone is the most appealing. Too many language learners are content with mediocrity. They’re satisfied with being able to communicate in English, albeit without using complex structures and varied higher level lexis.

Write down some goals. Go to war with those fossilised errors. Find some language learning strategies which are right for you. I came up with the Word-Phrase Table and it helped me become an advanced speaker of Serbian.

All in all, make a change today. You need to try to be a better version of yourself every day. Otherwise, the intermediate plateau will be your best friend for another ten years.

Good luck.

Reference:

Richards, J.C. Moving Beyond the Plateau: From Intermediate to Advanced Levels in Language Learning, Cambridge: CUP, 2008