How to think in English and stop directly translating from your mother tongue

If you’re wondering how to think in English, you’ve hit the jackpot.

Any serious English language teacher should be obsessed with two related questions:

1. How can I prevent learners from succumbing to fossilization? Fossilization refers to the permanent use of incorrect linguistic structures in speech or writing.

2. What mechanisms exist for learners to stop translating everything from their native language into English and begin to THINK in English?

MY FIRST PODCAST GUEST APPEARANCE GOT ME WONDERING

Back in 2021, I made my first ever podcast guest appearance. I spoke with Paul Sallaway, founder of BabelTEQ, about how ESL teachers can deliver value to intermediate English language learners. In particular, I focused on approaches teachers can employ to help learners who get stuck at the intermediate plateau in their skill development.

During the interview, I emphasised some of the language learning strategies and teaching tactics I constantly refer to on this site. Most notably, I stressed that it should be the teacher’s duty to demonstrate language learning strategies to their students, such as the Word-Phrase Table.

Secondly, preliminary trials with my students have shown me that voice recording, and the eventual self-analysis and self-correction students partake in, may help to eliminate permanent error patterns, unnatural intonation patterns and crosslinguistic influence, also known as negative language transfer. Negative language transfer refers to how a learner's mother tongue interferes with their learning of a second language, causing errors in areas like pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary selection.

Finally, I talked about the need for learners to regularly expose themselves to English. In my view, it’s more beneficial to have short lessons lasting around 25-30 minutes every few days than it is to have one long lesson each week.

Hence, a large part of the podcast was dedicated to ways to overcome the intermediate plateau and fossilisation. Vanpatten and Benati (2015, p.119) define fossilisation thus:

Fossilization is a concept that refers to the end-state of SLA, specifically to an end-state that is not native-like. By end-state, we mean that point at which the learner’s mental representation of language, developing system, or interlanguage (all are related constructs) ceases to develop

After the interview, I got caught on the thought that I need to teach my students how to think in English. Other blog articles which deal with “How to stop translating in your head and think directly in English” generally offer very shallow advice. For example, it’s far too simplistic to believe that watching movies can help you to think in English.

So, let’s dive in to find out what it really means to think in English. Let me also discuss three snazzy tactics which you can implement to bypass the process of translating from your first language to English.

WHAT does 'thinking in ENGLISH' ACTUALLY MEAN?

When people 'think in English', they’ve essentially internalised the language. Automaticity is key - speakers don’t need to remember grammar and pronunciation rules when they speak.

Another key trait of those who can think in English is that they’re no longer prone to negative language transfer.

Finally, it is my contention that those who are able to 'think in English' aren't actually doing much thinking at all whilst nattering away. Running around their minds are thousands of diverse types of 'chunks'. A chunk is a string of words that is stored in the memory as a ready-made unit. Knowing all these chunks leads to fluent speaking and writing due to the fact "we can just pluck them out of our memories whole, without having to mentally construct them word by word" (Lindstromberg and Boers, 2008, p.8). Examples of chunks include idioms, collocations and phrasal verbs.

How to train your brain to think in English?

To explain how to think in English, let me first of all rewind some eight years to my early days learning Serbian:

1. IMPLEMENT A LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGY EARLY DOORS AND STICK TO IT:

I was able to “think” in a foreign language after only half a year because I adopted a language learning strategy and stuck to it.

It wasn't my intention to base my Word-Phrase Table on just words and collocations. In fact, personalised sentences (true sentences about my life or situations familiar to me) containing target words and phrases were an essential element of my table.

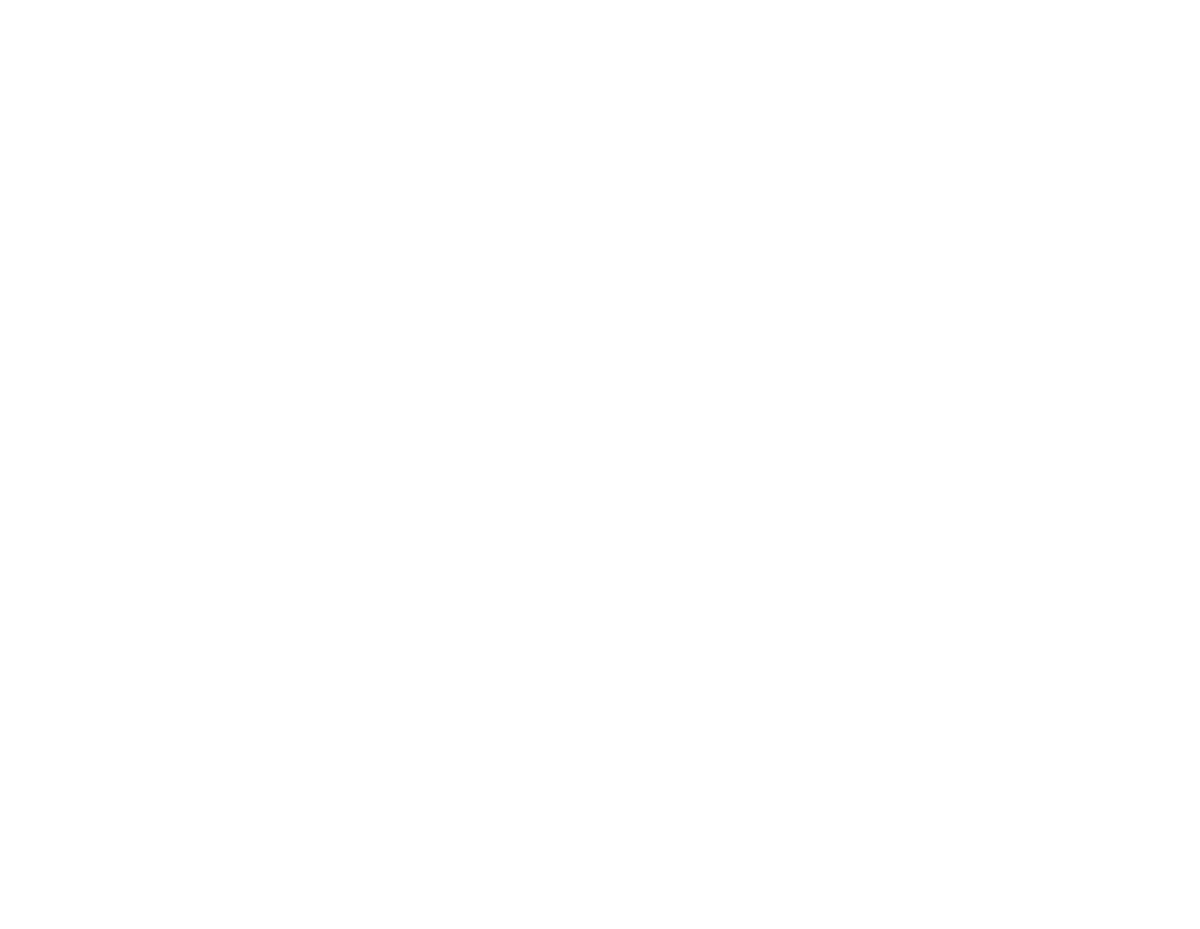

Looking at the above row from my table for the word “country”, I recorded collocations and useful multi-word units after a dash (-). I put personalised sentences after a star (*).

Hence:

- zemlja = country

- iz drugih zemalja = from other countries

- u tvojoj zemlji = in your country

* Bio sam u preko dvadeset zemalja = I’ve been to over twenty countries

Nouns in Serbian can be declined into seven cases. Frankly, I didn’t get bogged down with doing grammar gap fill exercises based on these cases. My only goal was to keep adding multi-word units and personalised sentences to my Word-Phrase Table.

The personalised sentence (Bio Sam u preko dvadeset zemalja) proved to be an excellent model for talking about life experiences and the declension of the noun 'zemlja'. 'Bio sam u' roughly translates to 'I was in'. Hence, I had to engage in some deep visualisation of 'Bio sam u' in order to avoid negative language transfer. Trying to directly translate 'I’ve been to …' wouldn’t work. I had to think in Serbian - 'I was in …'.

Communicating with others in Serbian on a daily basis, these model sentences would be 'swimming' around my mind. Essentially, I was constantly tuned in to my Word-Phrase Table. This is the key point. When I had to speak about my travel experiences, it was as if a switch would flick in my mind. I recalled this model sentence and the structure 'Bio sam u …'. Therefore, this method based on the personalisation of structures and chunks of language helped me to avoid negative language transfer in this and many other contexts.

Three types of speakers of English - become a motivated strategist

The way I see it is - there are three types of speakers of English:

1. Living bilingual dictionaries - Those who think that their first language is structurally and lexically identical to English. Hence, they believe that they can translate everything from their first language into English and Bob's your uncle!

2. Fossilised victims - Learners who picked up awfully bad habits at school, possibly from their teachers. Regardless of how much feedback and correction they receive, nothing seems to help when it comes to erasing grammatical and pronunciation errors from their speech.

3. Motivated strategists - Motivated strategists are those who have a language learning strategy in place to store new language items. They may be partly aware of how to think in English and self-correct when necessary. Nevertheless, they’re unaware of the benefits of personalising grammar structures, words and phrases.

All in all, my point is that you need to adopt a language learning strategy and stick to it. The personalisation of language items is also vital.

2. VISUALISATION AIDS THE LANGUAGE LEARNING PROCESS

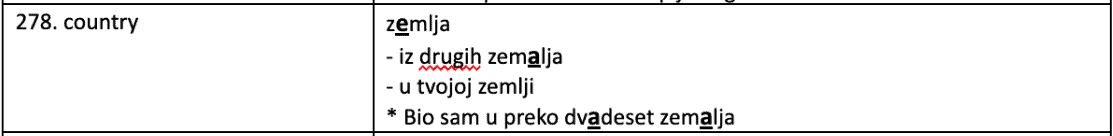

To help you remember grammar structures, cases and collocations, you need to engage in deep visualisation. If, for example, I had trouble recalling the genitive plural form 'zemlja' (country), I would do something visual with the word. I’m very much a visual learner, and I react well to larger font sizes and different colours:

Many learners who complain they don’t know how to think in English become obsessed with learning grammar tense rules. It’s sometimes a prudent move to organise grammar rules and tenses numerically. For instance, learners should focus their thoughts on the pattern 1-2-2-2-2 when talking about life experiences.

The number 1 represents the introduction to the life experience without giving specific details regarding dates and times. For example, “I’ve been to Berlin four times”. This is the present perfect tense.

Conversely, the details which follow are in the past simple tense. There may be many details so there will be quite a few number 2’s. Therefore, we have a numerical pattern for detailing life experiences: 1-2-2-2-2. Evidently, the present perfect doesn’t feature very heavily. The past simple does most of the work.

Overall, by mentally visualising numbers, colour and different fonts, you can begin to recall all of these personalised sentences and life experiences when you’re in full conversational flow. Another side-effect of all of this visualisation and instant recall of personalised sentences is a scintillating increase in accuracy.

3. DON’T RUSH YOUR READING

I am very much of the opinion that reading and speaking skills have a reciprocal relationship. In other words, as one skill increases, so does the other.

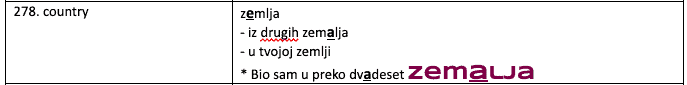

First of all, you need to build a relationship with the texts and articles you read. Let’s break down the steps you should take to get the most out of your reading. We’ll use a section from one of my texts as reference:

1. Don’t be a “copy and paste learner” - Read through the text a few times in silence. Concentrate and absorb the language in front of you. If you don’t know the meaning of a word or phrase, try to guess from context. Don’t just copy the text and paste it into Google Translate to see what’s going on in your mother tongue.

2. Have a pen and piece of paper handy - If you come across a handy phrase or word, jot it down on a piece of paper or add it to your Word-Phrase Table. Say the word or phrase aloud three or four times to help you internalise it.

3. Stop, notice, analyse - Draw comparisons between your mother tongue and English - look out for structures which are formed differently to the way they are in your mother tongue. In the section above from one of my texts, it’s worth stopping, noticing and analysing the use of the present perfect. Many Polish learners of English might say “I was in twenty-five countries”, a clear case of negative transfer. Take the English structure - I’ve been to - and say a few personalised sentences about your life experiences aloud: “I’ve been to five countries in Asia”, or “I’ve been to so many places in Italy”. You can even add 'I’ve been to' to your Word-Phrase Table, and add sentences relating to your travel experiences under that particular structure.

4. Revisit texts - Set up a schedule which enables you to revisit texts and news articles several months after the first reading. Check your comprehension of key words and collocations.

CONCLUSION - HOW TO THINK IN ENGLISH THE RIGHT WAY

If a student asks me how to think in English, I can only tell them that the journey to the promised land is an arduous one.

Without consistently making use of a language learning strategy, it's an uphill battle to become an advanced speaker of English. With a bit of work, you can have all those correct structures, collocations and personalised sentences running around your mind during your future conversations.

References:

Lindstromberg, S. and Boers, F. (2008). Teaching Chunks of Language: From noticing to remembering, Innsbruck: Helbling Languages

Vanpatten, B., and Benati, A.G. (2015). Key Terms in Second Language Acquisition, Second Edition, Bloomsbury Academic: London