Imposter Syndrome Theory and the EFL teacher

This time around, I'm going to tackle the topic of “imposter syndrome theory” in EFL..

Without further ado, let’s find out what imposter syndrome theory is all about. In the second half of the post, I touch upon how I’ve experienced imposter syndrome over the years.

WHAT IS IMPOSTER SYNDROME THEORY?

Imposter syndrome theory, also known as the Imposter Phenomenon, is a psychological trait in which an individual questions their own talents, achievements or skills.

Those who experience this phenomenon can’t shake off an internalised fear that they will be exposed as a “fraud”.

Individuals with imposterism pin their success down to luck. Alternatively, they believe their success stems from tricking others into thinking they’re more intelligent than they perceive themselves to be.

THE ORIGINS OF THE TERM “IMPOSTOR PHENOMENON”

In their 1978 article, "The Impostor Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention", Dr. Pauline R. Clance and Dr. Suzanne A. Imes introduced the term Impostor Phenomenon.

Across a five-year period, Clance and Imes had contact with over 150 highly successful women. However, regardless of the degrees these ladies earned, not to mention other scholastic achievements and professional recognition from colleagues and respected authorities, these women failed to internalise their accomplishments.

Hence, the opening words in the abstract of Clance and Imes’s article:

"The term impostor phenomenon is used to designate an internal experience of intellectual phoniness which appears to be particularly prevalent and intense among a select sample of high achieving women"

HOW DID IMPOSTER SYNDROME THEORY DEVELOP AFTER 1978?

In 1985, Clance suggested that the Impostor Phenomenon is characterised by six potential attributes:

(1) The Impostor Cycle;

(2) The need to be special or to be the very best;

(3) Superman/Superwoman aspects;

(4) Fear of failure;

(5) Denial of competence and Discounting praise;

(6) Fear and guilt about success/

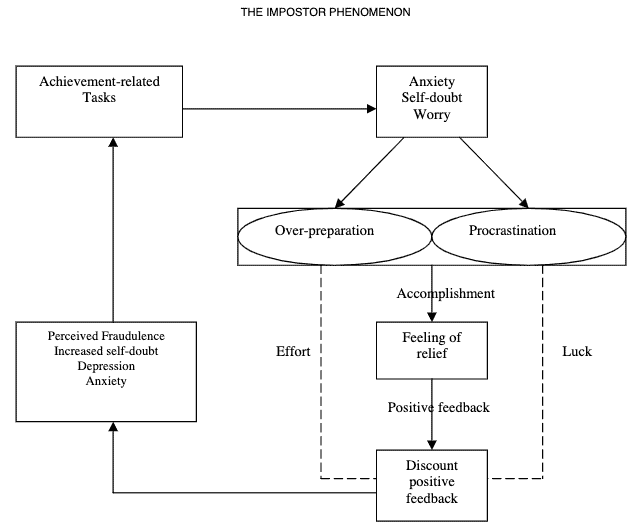

As Sakulku and Alexander (2011) acknowledge in their article “The Impostor Phenomenon”, the Impostor Cycle is one of most defining characteristics of the Impostor Phenomenon:

Diagram illustrating the Impostor Cycle (in Clance, 1985). The cycle begins with the assignment of achievement related tasks.

I’ll touch upon this cycle and some of the other traits below when I reveal my own experience of the Imposter Phenomenon.

MEN AND THE IMPOSTER SYNDROME

Original studies in the 70s and 80s rather focused on how the Imposter Phenomenon affects women. However, as coach Davina Houlton touches upon in this post, imposter syndrome also afflicts men. Thankfully, more and more men are beginning to speak out on how imposter syndrome has blighted their career.

Honestly, I believe that speaking out, sharing my innermost thoughts and admitting to my weaknesses proves that I have courage. I have to reveal my vulnerabilities to be able to understand who I really am. Being frank and exposing myself will only make me stronger in the long run.

We guys can read all the self-help books in the world. However, I don’t believe we can achieve true inner peace until we reveal our deepest insecurities, fears and weaknesses.

THE RELEVANCE OF THE IMPOSTOR CYCLE DURING THE CELTA COURSE

Unfortunately, self-doubt has sabotaged certain phases of my career.

It all started when I did the CELTA in Kraków in 2006.

Actually, I arrived in Kraków feeling like a fraud because I had just graduated in history. Who was I, with my non-linguistics degree, to embark upon a career as an English teacher?

Still, it wasn’t as if I was averse to the English language. I’d always liked creative writing and working with words. However, it had never been my plan to teach English as a foreign language. That is, until a chance meeting with a Polish student at university in Nottingham changed the course of my life.

Naturally, I compared myself with my CELTA coursemates. In my eyes, they all seemed to be quite laid-back about everything. Whenever they had a task to complete or an assignment to write, they didn’t seem to be racked with worry and anxiety. Conversely, I felt lost, constantly flirting with over-preparation, on the one hand, and baffling procrastination on the other.

I got a ‘pass’ grade for my CELTA. The majority of candidates receive this grade. Nevertheless, I felt like a fraud once again. I put my ‘pass’ grade down to luck and my fallacy that nobody fails the CELTA.

In fact, only around three per cent of people do fail the CELTA. Nevertheless, I still felt like I didn’t deserve to pass the course. I believed that all of the other candidates were better teachers than me. In my eyes, their classes were more interesting than mine. Alarmingly, I just thought that they were more likeable people than me. More likeable to the course tutors, and more likeable to the students we taught.

THE OVER-PREPARATION AND SUPERMAN PARTS OF THE IMPOSTER CYCLE

After my CELTA, I started my TEFL career at a school in Dębica, southeastern Poland.

I spent countless hours slaving away on lesson planning in the teachers’ room. It’s possible that I pushed myself to work harder than those around me to prove that I wasn’t some kind of impostor.

I obsessed over finicky grammar issues and timing my lessons perfectly. It took me a good few years to realise that life’s too short for such trivialities. Besides, students generally aren’t capable of applying the grammar they’re taught in class in everyday conversation. Hence, I came to recognise that it’d be more sensible to adopt a more conversational approach in the classroom.

THE NEED TO BE SPECIAL, TO BE THE VERY BEST

Clance (1985) reported that impostors are often “top of the class throughout” pupils throughout their school years.

In my youth, I invariably came out on top in writing and spelling tests. Indeed, I had a reading age of fifteen when I was only nine years old.

With such results, it was inevitable that I would harbour high expectations with regard to my university studies and my future career.

Not only that, there was always the danger that I would feel worthless and stupid if my peers or colleagues performed better than me.

At one language school I worked for, children wouldn’t shy away from voicing their opinion as to who was the best native speaker teacher they’d ever had. Unfortunately, I wasn’t Mr Popular among both my colleagues and my students. Therefore, I did begin to feel a certain level of humiliation and shame.

They were only kids, but some of their remarks caused me to over-analyse the situation. It was my second year in EFL and I was still over-planning my lessons. Moreover, I just couldn’t believe that any other teacher had tried harder than me to teach those kids. Hence, I came to question my personality and approach to students. Was I really born to be a teacher?

2021: SOME DIFFICULTY INTERNALISING MY “SUCCESS” - BUT THINGS ARE GETTING BETTER

Another characteristic of the Impostor Phenomenon proposed by Clance (1985) is the denial of competence and discounting praise.

Unfortunately, I used to discount all positive feedback that came my way - either from colleagues, students or my employers. I never used to count myself as a successful person.

These days, I’m able to react to some unobvious indicators of 'success'. For instance, I’ve been teaching many of my students for over five years. It must be a sign that I'm doing something right if they've stuck with me for so long. These students are still fighting with the English language. Fighting to improve. They don’t need to verbally praise me, and nor would I like them to.

Overall, not many of my students drop out, which I’ve grown to recognise as 'success'.

I’m a modest being. For me, pride, personal satisfaction and signs of development among my students count for so much more than my bank account account balance.

CONCLUSION - HOPEFULLY, I’M NOT A PHONeY EFL TEACHER

I imagine that imposter syndrome theory is relevant for many EFL teachers.

With some conviction, I can say that all EFL teachers need to consider where they stand in terms of their beliefs about instruction and insecurities concerning the impostor phenomenon.

Many EFL teachers 'fall into' EFL by accident or because they don’t know what else to do with their lives. Indeed, EFL never crossed my mind until I returned to the UK after my first trip to Poland.

Nevertheless, I’ve just about come to terms with the fact that I’ve been successful BECAUSE I’VE BEEN TRUE TO MY PRINCIPLES AND BELIEFS.

“Success” is a relative, debatable word anyway.

References:

Clance, P.R. and Imes, S.A. 1978. "The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, Vol. 15, No.3

Clance, P. R. (1985). The Impostor Phenomenon: Overcoming the fear that haunts your success. Georgia: Peachtree Publishers.

Sakulku, J. and Alexander, J., 2011. "The Imposter Phenomenon", International Journal of Behavioral Science, Vol.6, No.1, 75-97