The Kato Lomb reading method of learning foreign languages

In this post, I analyse the “Kato Lomb reading method” of learning foreign languages. Essentially, the “Kato Lomb reading method” revolves around reading and deciphering an interesting novel in the second language in order to unravel the key elements of its grammatical and lexical systems.

After an eight-year break from studying and speaking Polish, I’ve also adopted the “Kato Lomb reading method” to see if I can get back up to speed again.

More to come on my progress in Polish in my next post.

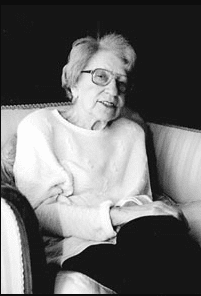

Who was Kató Lomb?

Born in Pécs, Hungary, in 1909, Kató Lomb was a prolific translator and interpreter. She was also one of the first simultaneous interpreters to grace our planet.

Lomb worked as an interpreter and translator in no fewer than 16 languages.

Those languages were Bulgarian, Chinese, Danish, English, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Latin, Polish, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Ukrainian.

Lomb also learned another 11 languages, all of which enabled her to read for pleasure.

Part collection of anecdotes and reflections on language learning and part memoir, Lomb’s most famous book is How I Learn Languages.

The legend Kató Lomb

The early life of Kató Lomb

Strangely, Lomb was indifferent to foreign language study at school. In junior high school, she considered herself to be “far behind her classmates who were of German origin or who had had German nannies.” (p.23).

Modest as ever, Lomb wrote in How I Learn Languages that she was nothing more than a “foreign language flop” when she finished high school (p.23).

Lomb actually had a scientific background. After high school, she applied to do a degree in natural sciences. Her PhD was in chemistry.

The above information is not to say that Lomb hadn’t dabbled with linguistics nor fallen in love with languages in her teenage years.

Indeed, when coming across a page full of Latin proverbs, she spelled out the sentences and their approximate Hungarian equivalents with joy. Lomb did this despite not having ever formally studied Latin.

At junior high, Lomb enrolled in an extracurricular French class. “Filled with ambition”, she became class monitor after a month.

How did Lomb’s association with language learning begin?

Lomb failed to see a future in the sciences.

Like most countries in the early 1930s, Hungary was in a deep economic depression. Lomb had to figure out what to do with her life. She decided to make her living teaching languages.

There were too many French teachers in Budapest. Hence, Lomb set her sights on learning English.

Just a good old novel: The Kato Lomb reading method of learning languages

Lomb claimed that a good method “plays a much more important role in language learning than the vague concept of innate ability.” (xi)

I couldn’t agree more.

I wouldn’t have learned Serbian in the short time I did without storing personalised sentences containing newly-learned words and phrases in a Word-Phrase Table. By 'personalised sentences' I mean true sentences about my life experiences, current employment status, current interests and hopes for the future.

Anyway, to learn English, Lomb started by intensively studying a novel by English novelist and playwright, John Galsworthy. Lomb would read her books several times.

At first reading, she focused only on those words which she recognised or could figure out from context. Lomb didn’t write out these words in isolation. Instead, she copied them out in their original context. Hence, the opening phase of Lomb’s method was centred upon her refusal to look up any words she didn’t understand.

After a second or third reading, Lomb would look up unknown words in a dictionary, but not all of them. For those words she recorded in her notebook, she included the context that was supplied by the book or a dictionary.

When it came to grammar, Lomb dealt with it “on the go”. She deduced a language’s rules through repeated exposure to the grammatical patterns that would crop up again and again throughout a novel.

Going back to her study of Galsworthy’s novel, Lomb wrote:

Within a week, I was intuiting the text; after a month, I understood it; and after two months, I was having fun with it

KATÓ LOMB

For Lomb, this journey of discovery was exhilarating:

to go from incomprehension to half-understanding to complete understanding is an exciting and inspiring journey of discovery worthy of the spirit of a mature person. By the time I finish the journey, I part with the book feeling that this has been a profitable and fun enterprise

KATÓ LOMB

Central to the Kato Lomb reading method - Note-taking and margins

Lomb very much valued taking down notes of rules and new words and phrases in a book’s margins.

She posed the question: “What shall one write in the margins?” Lomb urged readers to note down only the phrases and forms that can be easily understood and decoded from context.

If you automatically consult a dictionary for every new word or phrase you come across, the relationship that develops between you and the knowledge you obtain WILL BE much shallower. As Lomb wrote, if the word is important, it will come up again anyway and its meaning will become clear from the context.

Interestingly, Lomb recommends “untidy glossaries”. In her words, neatness and “uniform pearly letters … make you sleepy” (p.114). Hence, memory has very little to cling to when everything is so neat and tidy. I don't doubt that writing with different instruments (coloured pencils and pens) in various styles (slanting, upright, capital letters, small letters, etc.) can work wonders for the memory.

Overall, then, Lomb’s success was largely down to her tolerance of ambiguity and messiness.

All of this ambiguity and messiness can still lead to useful language production. At the end of the day, sentences full of mistakes “can still build bridges between people” (xii).

It’s a huge lesson for perfectionists like me who are intent on harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance.

A foreign language is a castle

The Kato Lomb reading method may have revolved around the reading of novels. However, it becomes apparent in Lomb’s book that she had a far more wide-ranging approach to mastering languages.

In Lomb’s words, “a foreign language is a castle.” She advises language learners to “besiege” a language from all directions. These various methods include newspapers, radio, scientific and technical papers and motion pictures (undubbed).

News bulletins

News items are usually the same in the broadcasts of different languages. Therefore, to give herself a head start, Lomb would listen to the news in a familiar language. This gave her a “key”, or “almost a dictionary”, as to what she could expect in advance.

Thereafter, Lomb would return to the news bulletin in the less familiar language. She would note down unknown words along the way. After the broadcast, she looked up the words in a dictionary. This immediacy of checking words after a bulletin was important because they still resounded in her ear along with the context in which they were found.

Dictionaries

Apart from novels, Lomb was also fascinated by dictionaries.

She wrote proudly of stooping over “the only Chinese-Russian dictionary to be had at any public library” (p.32). From there, Lomb would attempt to transliterate words from Chinese. A few days later, she tried to decipher her first Chinese sentence: “Proletarians of the world, unite!”

Two years down the line, Lomb found herself interpreting for the Chinese delegations arriving in Hungary. Moreover, she was able to translate some of her favourite novels.

Lomb also used dictionaries to learn the rules of a language and how a language “morphs the parts of speech into one another” (p.148). She also worked out how verbs are nominalised (converted into nouns) and how adjectives are formed from nouns.

The world we live in revolves around self-entitlement and quick fixes. Processes no longer matter. It’s all about the final result. Therefore, one must admire Lomb for just getting a taste of languages through using dictionaries. To begin with, all she wanted to do was “make friends” with a language.

The good old days indeed.

Final Thoughts

The title of one of author Alina Kuimova’s articles is: 21 Century: Is It Still Possible To Learn A Language By Reading?

Kuimova argues that the Kato Lomb reading method of learning foreign languages “will significantly slow your progress down should you apply it nowadays”.

I’m not so sure.

I’m using Lomb’s reading techniques to pick up Polish right now. I have to say that it’s very motivational and effective. Certainly, I don’t feel that my progress is slow.

Kuimova points out that we have more learning resources and tools available these days. Not to mention less time. However, can we really compare the quality of these resources to the quality of a riveting novel?

Technology and the wide availability of resources are part and parcel of modern day language learning.

However, I don’t think they’re helping to churn out that many influential and highly-motivated polyglots like Lomb.

Let’s not consign old-school language learning methods to the dustbin of history just yet.