Learn English through true stories written and recorded by native speakers

My main goal over the next few years is to enable the wider English language learning community to learn English through true stories.

The plan of action is for native speakers of English from the US, Canada, UK and Australia to share true stories about their lives in both written and voice recorded form.

In fact, I plan to include all of these stories in one of the courses in Komified - a mobile app for English language learners.

LEARN ENGLISH THROUGH TRUE STORIES - THE ORIGINS

I started to share snippets of my life with my students back in 2014. My main aim was to acquaint them with features of spoken English that native speakers typically use.

Representing elements of informal spoken English in a written text - a tough challenge, right?

Well, it’s not exactly a doddle.

However, I believe that it's much tougher to pick up English through articles found in coursebooks.

Articles in coursebooks are too fact-based and obscure for my liking. The authors barely pay heed to spoken English when they write them. Don’t get me started on the questionable motives of publishers.

So, I knew that I needed to take my students in a different direction.

Therefore, I started to write texts about my travels around Europe and the USA, as well as some of my own experiences living and working in Poland, UK Bosnia and Serbia. I also wrote about common everyday situations, such as quarrels with neighbours and renting apartments. Finally, I shared my opinions on stories in the news.

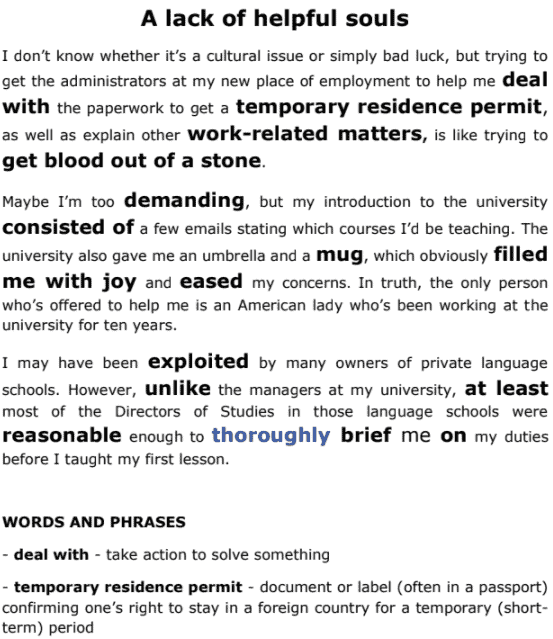

Here’s a text I wrote about my experience working at a university in Serbia:

HOW CAN LANGUAGE LEARNERS BENEFIT FROM TRUE STORIES WRITTEN AND VOICE RECORDED BY NATIVE SPEAKERS?

Using the text above as a guide, here are what I consider to be the biggest advantages of learning English through true stories written by native speakers:

1. The use of the first person “I”

I’ve always felt that articles found in coursebooks and on the Internet are too descriptive and 'newsy'.

When you learn English through true stories that are in the first person, you’re really able to put yourself in the shoes of the author and relate to their experiences on a psychological and emotional level. Consequently, ripe conditions for deeply immersive learning and acquisition ensue.

2. Opportunities for copying and pasting clauses and sentences into Word-Phrase Tables

If a language learner has had similar experiences to the author of a true story, or indeed agrees with specific points of view, it makes sense for them to copy and paste sentences from these stories into their Word-Phrase Tables.

Language learners can store all newly learned words, collocations and personalised sentences in these Word-Phrase Tables. By 'personalised sentences', I refer to true sentences about one's life experiences, current work-life situation, hobbies and future plans and aspirations.

Rereading personalised sentences over and over again ensures that they’re constantly “swimming” in the brain during conversation. This is the essence of fluency - having a stock of personalised sentences running around the mind just waiting to be retrieved and spoken.

3. Learners might just come out of their shell

It’s natural that when a language learner has seen their teacher put so much effort into writing, revising and audio recording a text, then he/she might feel encouraged to go the extra mile and speak at length when the teachers ask questions about the topic of the text.

In my experience, my most opinionated and controversial texts have encouraged even quite reserved students to speak at reasonable length in response to my views.

The name of the game for us EFL teachers is to get learners to speak with freedom and be opinionated themselves. By hook or by crook, we need to get learners to break the shackles of the language barrier.

4. Multi-level compatibility

The beauty of true stories is that they cater for learners of varying abilities.

Frankly, it’s debatable what 'intermediate' and 'advanced' actually mean anyway.

Moving on, it’s my contention that the sheer depth of grammatical structures in these true stories, not to mention the marked variety of lexis and collocation, fits in nicely with Stephen Krashen’s Comprehensible Input Hypothesis.

Essentially, Krashen argued that in order for acquisition to occur, the learner should receive ‘input’ that is slightly beyond his/her current level of linguistic ability (i + 1).

Therefore, learners should understand the main messages of a text or piece of listening material. Potentially, then, the learner should be able to deduce the meaning of uncertain lexis and sentence parts from context.

Krashen called this kind of input ‘Comprehensible Input’. This is input that’s understandable but still reasonably challenging.

Enabling students to learn English through true stories ensures that they receive challenging i+1 input.

Even the most experienced and highly-proficient English language buff will come up against a few challenges with these true stories.

For instance, in the last paragraph of the text above, I may have been exploited has a slight nuance in meaning which I suspect few learners of English would recognise:

In the context of this text, I may have been functions as a negative concession before moving on to say something more positive. In other words, many owners of schools financially exploited me. Nevertheless, at least some of them and the Directors of Studies they employed in those schools tried to help me at the beginning of my employment period.

Therefore, I may have been rather means “I confess that …”

5. Raising students' levels of cultural intrigue

When I write a text, it’s not my intention to churn out stories solely related to work and teaching.

I try hard to get across my observations of other cultures in which I’ve been immersed in my life. Indeed, I’m very familiar with the cultures of Serbia, Bosnia, Poland and Great Britain as I’ve lived in these countries for extensive periods of time.

For instance, I’ve written about the ins and out of British humour and comedy. I’ve also written some tongue-in-cheek scripts about the aggressive tactics deployed by vendors at green markets in Serbia and Poland. Finally, I recall writing a piece about the way in which Bosnian Serbs do their utmost to maintain close family relations.

6. Driving home the importance of using contractions instead of full forms

I’ve written over ninety texts and they’re all littered with a plethora of contractions (short forms).

A contraction is a shortened version of the spoken and written forms of a word or group of words etc.

Contractions are built via the exclusion of internal letters and sounds.

For example, if the full form is I am, then the contracted form is I’m.

Contractions are natural features of natural spoken English. Using them helps to speed up speech and create that all too important perception of fluency.

7. Familiarisation with connected speech and the schwa sound

I always get my voice-over actors to pay heed to natural connected speech patterns when recording true stories.

Connected speech occurs when a word ends in a certain letter or sound and the following word begins with a certain letter or sound.

Between these two sounds, we insert an extra 'glide' sound to create a smooth connection between the two letters or sounds.

For example, in the text above we have “gave me an umbrella”. This :i sound at the end of me and schwa sound at the beginning of an would be a classic example of when to insert a /j/ sound between two words ending and starting with vowel sounds.

Hence, saying “me an” together would sound like mijuhn, almost like a single word. This is in contrast to mi: ahn - whereby the words are pronounced in their full forms.

In these texts, I also place a great deal of emphasis on the schwa sound. The schwa is a weak vowel sound in an unstressed syllable. For example, compare the strong and weak forms of the word to:

strong /tuː/ weak /tə/

The ‘o’ in to is reduced to schwa in rapid speech.

By using schwa and weak forms, English language learners would be one step closer to spoken fluency.

REAL LIFE STORIES WRITTEN BY NATIVE SPEAKERS OF ENGLISH FROM NORTH AMERICA, GREAT BRITAIN AND AUSTRALIA

For my mobile app, I’ve found some willing voice actors from North America, Great Britain and Australia to both write and sound record a story about themselves.

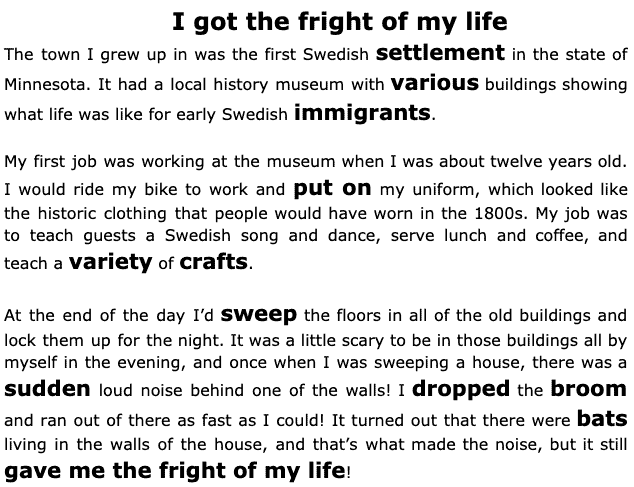

Here’s a story by Abbey from Minnesota. Well, you do indeed learn something new every day. I had no idea that there was a mass migration of Swedish people to the USA in the 1800s:

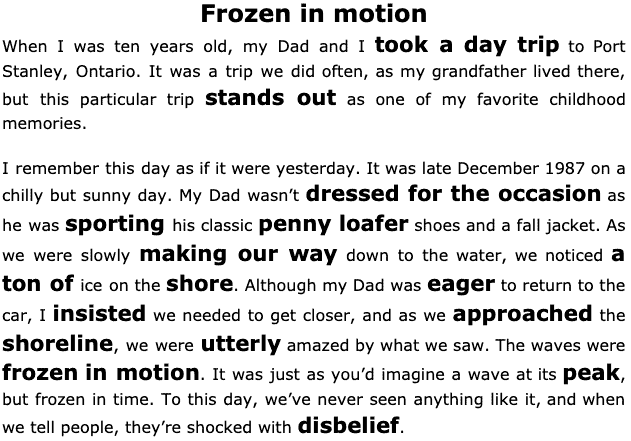

Tina, from Canada, wrote this story:

JUST SNIPPETS OF ORDINARY PEOPLE’S LIVES

I strongly believe in the notion that open-minded students can learn English through true stories.

English language learners shouldn’t have to solely rely on news articles and feature stories written in the third person.

I’m searching for something a little different.

My flourishing database of true stories and snippets of ordinary people’s lives will surely influence the linguistic development of my students for many years to come.