The Present Perfect Simple – The Most Difficult English Tense to Acquire

Last time around, I explored the main uses of the present perfect simple tense - arguably the most difficult English tense for learners to weave into their idiolects. I also summarised the main time adverbials associated with the present perfect.

In this post, I examine the main challenges learners face when it comes to acquiring the present perfect tense.

The present perfect as the most difficult English tense to acquire - Challenges

English language learners seeking to embed the present perfect within their idiolects have to contend with a plethora of ambiguous and oversimplified rules.

Let’s check out three of the biggest challenges learners have to grapple with regarding the acquisition of the present perfect.

1. The present perfect and ‘current relevance’

The idea that ‘current relevance’ is the basic meaning of the present perfect, as Swan (2017) claims, requires conscientious scrutiny.

Here are Swan’s exact words (2017: 93)

We do not use the present perfect if we are not thinking about the present.

Read more widely on the topic of ‘current relevance’ and the present perfect, and you begin to realise that Swan’s claim is nothing more than a wild generalisation.

Another author who trumpets the ‘current relevance’ stance is Bernard Comrie (1985: 25):

The perfect indicates that the past situation has current relevance (i.e. relevance at the present moment), while the simple past does not carry this element of meaning.

It seems that Comrie (1985: 25) entered into very biased territory with this example:

John has broken his leg - it happened six weeks ago, and it still hasn't healed.

I’m not sure many people would combine the present perfect and past simple in such a matter-of-fact way when giving news:

John has broken his leg - it happened six weeks ago.

Wouldn’t it be more natural to use the past simple followed by the present perfect?:

John broke his leg six weeks ago and it still hasn’t healed.

Regardless of the time frame (John broke his leg six weeks ago or John broke his leg last week), who’s to say that the past simple tense does not exhibit ‘current relevance’?

Frankly, if I broke my leg a few days ago, I think it’d be a more than relevant situation today.

Authors opposed to the ‘current relevance’ element of the present perfect

‘Current relevance’ is a particularly vague concept for Renaat Declerck in his 1991 book Tense in English: Its structure and use in discourse.

According to Declerck (1991: 173):

… current relevance is no more than an implicature of the use of the present perfect, and that there are therefore many cases in which the present perfect is used without triggering a current relevance interpretation.

Take these sentences, for example (in Declerck, 1991: 320):

A: Have you always lived here?

B: No, I have lived in London too, but that was a long time ago

Clearly, there is no suggestion of ‘current relevance’ in B, despite the use of the present perfect.

Let’s now look at an example sentence containing the past simple (in Declerck, 1991: 236):

I know what Tom is like. I spent my holidays with him two years ago.

There is certainly ‘current relevance’ here. I know what Tom is like because I spent my holidays with him. However, as the time wholly precedes the present moment, we have to use the past simple.

Like Declerck, Wolfgang Klein (1992) also promotes the idea that the past simple can have ‘current relevance’. Here’s one of the two examples Klein offers (p.531):

Why is Chris so cheerful these days? - Well, he won a million in the lottery.

Similar to Declerck and Klein, Close (1992: 70) argues that students should not assume that we use the present perfect just because a result is evident. Close mentions that other tense forms can also imply present evidence. Moreover, this author also raises the point that we can use the present perfect when a noticeable result is markedly different to what might have been expected:

Look at you! You’ve just had a bath and now you’re filthy.

Solutions for teachers and learners to the ‘current relevance’ problem

The present perfect tense is the most difficult tense in English because there are so many unpredictable situations and contexts which throw a spanner into the works of the ‘current relevance’ argument.

For Declerck and Close, the chief factor dictating the use of the present perfect and the past simple is not the presence or absence of the concept of ‘current relevance’. Instead, it’s important to look at how a situation is located in time.

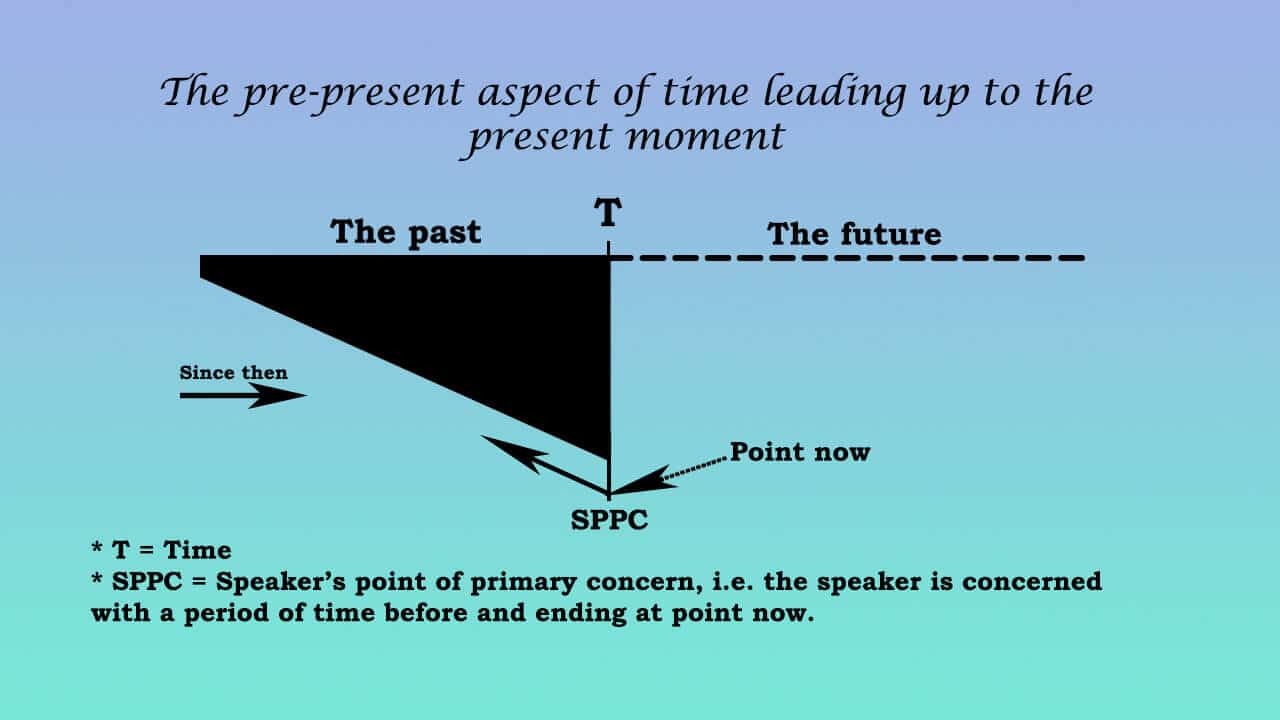

Close urges students to consider the time aspect in this diagram which highlights the need to concern oneself with occurrences within the pre-present period:

Source: Close (1992), p.68 (Fig.22) (Adapted)

Students need to see countless example sentences which highlight the “role that adverbials and context play in the way that situations are located in time” (Declerck, 1991: 234). Online corpora should be every serious teacher's and learner’s go-to resource for these sentences.

Finally, let me finish this section with the words of Wolfgang Klein (1992: 531).

… it is always possible to find a reason why the event is still of particular relevance to the present.

I couldn’t have put it better myself.

2. Choosing between the present perfect simple and the present perfect continuous tenses

There are very many overlaps between the present perfect simple and present perfect continuous tenses. This is another factor which contributes to the present perfect being the most difficult English tense to retrieve and apply with confidence in conversation.

Traditionally, English language students are taught to use the present perfect continuous when measuring the “duration so far of a present action or to specify when it began” (Parrott, 2000: 237). Moreover, the continuous form is heavily linked to expressions beginning with the prepositions for or since, or the question How long …?

Learners face several challenges when it comes to correctly using the present perfect simple form. Let me describe what these challenges are:

Challenge 1 - The open choice factor

Learners can choose between either the present perfect simple or present perfect continuous tenses in certain contexts.

Similar to the present perfect continuous, we can use the present perfect simple when measuring the duration of a present action or indeed determining its commencement. The prepositions for and since, as well as the question How long …? can be used in conjunction with the present perfect simple.

When describing general (biographical) facts, we can select either the simple or continuous form:

He’s smoked/been smoking since he joined the army in 1975

The reason that this open choice factor poses a challenge for students is because they might adopt the habit that they can use either form in any context.

Challenge 2 - There’s more to the open choice factor than meets the eye. Students are very likely to get bogged down in the details

It’s all very well having an open choice between the continuous and simple forms when it concerns duration.

However, what about when it comes to short-term and long-term duration?

Parrott (2000: 237) points out that we tend to choose the simple form to emphasise long-term situations. Conversely, the continuous form tends to go with short-term circumstances:

Simple: I’ve lived here most of my life (i.e. long-term)

Continuous: I’ve been working here for just a few days (i.e. short-term)

Challenge 3 - The repetition factor

We tend to use the present simple form for long-term situations. Therefore, it could be potentially baffling to students that we generally apply the continuous form for repeated actions over a period of time. Over to Parrott (2000: 238) again:

Simple: I’ve used the gym since we moved into the area (i.e. on one or two occasions)

Continuous: I’ve been using the gym since we moved into the area (i.e. repeated)

Challenge 4 - The state verb factor

Learners of English need to remember that there is a set of verbs which we tend to avoid using in present continuous and present perfect continuous tenses.

These verbs are called state verbs. They tend to describe thoughts and opinions, feelings and emotions, senses and perceptions, possession and existence.

Examples of state verbs include agree, prefer, know, have and hear.

Therefore, with classic state verbs such as know, the learner should resort to using the present perfect simple:

I’ve known about the faulty boiler for weeks.

Challenge 5 - The completed result factor

Learners need to be wary of the generalisation that only the present perfect continuous describes an activity that's recently stopped, as in:

I’ve been reading ‘War in Peace’

The following sentences may describe the same ‘recently stopped activity’. Pay attention to the differences in meaning that are described:

Simple: He’s painted the room (focus on the completed result, a sense of achievement)

Continuous: He’s been painting the room (focus on the activity itself - the fact that someone is covered in paint, for example)

__________

Overall, there are some very subtle nuances in meaning between the present perfect simple and present perfect continuous forms. This contributes to the simple form being the most difficult English tense to retrieve correctly in conversation.

It’s a similar story when it concerns the past simple and present perfect tenses, as I shall now investigate.

3. Choosing between the present perfect simple tense and the past simple tense

The third and final factor which I believe makes the present perfect the most difficult English tense to acquire is the difficulty students face when it comes to choosing between the present perfect simple tense and past simple tense.

As I shall demonstrate below, there are plenty of overlaps between the simple past and the simple present perfect with no difference in meaning.

Another issue that’s worthy of attention is how wary we need to be when it comes to simplifications and 'rules of thumb' often put forward by coursebooks and grammar manuals.

Let’s take a look at some of the most pertinent areas of contention concerning the past simple and present perfect tenses.

(a) The adverbial question

As you most likely know, there is a set of past time indicators and adverbs of time which accompany the past simple tense. For example:

last night, last week, five minutes ago, when I was a child, yesterday

The same applies to the present perfect. When one wishes to place an action within a period of time which extends from a particular point in the past up to the present moment, the speaker uses the present perfect simple to recount the action. The following time indicators typically go with the present perfect:

this month, this morning, this year, recently, lately, already, yet, ever, never, up to now, so far

Still, learners cannot rely on these indicators of time in order to successfully produce either the present perfect or the past simple. This is because the majority of time indicators can be used with both tenses. These indicators include:

today, this morning, this afternoon, this evening, tonight, this week, this month, this year, recently, never, ever, already, for

A few stark reminders

Declerck (1991: 304) reminds us that the past tense is also compatible with INDEFINITE adverbials of time.

Consider the following examples with such indefinite time indicators:

All this was a long time ago

The expected disaster never occurred

It happened at some point before the Great Depression

John lived in Boston for some time

Declerck (1991: 304) goes on to mention that the present perfect can also refer to specific events and a specific time in the past using the following examples:

I have just met your brother [a specific time denoted by the adverb just]

Jackie has bitten Molly before [a specific occasion denoted by the adverb before]

The importance of time frames when it comes to adverbial use

Walker (1967: 18) claims that the choice of verb tense that appears in conjunction with one of the time indicators in the last set above (i.e. one that can be used with either the past simple or the present perfect) depends upon whether an action took place within:

a. a period of time before now and completely separated from now (i.e. a past time frame);

b. a period of time beginning before now and including now (i.e. a present time frame).

However, I pointed out in section 1 that it’s a fruitless task to attach certain rules to tenses (i.e. the ‘current relevance’ debate is a particularly complex one). Indeed, plenty of examples exist which prove that some actions which take place within a past time frame might not be “completely separated from now”.

‘Current relevance’ is not the only factor to consider regarding this set of time indicators that can be used with both tenses.

Sometimes, we just need to consider the time frame we’re in when choosing between the past simple or present perfect, alongside the use of a time indicator.

Compare the following sets of sentences:

1)

Present perfect simple: I’ve seen Jenny a few times today

Past simple: I saw Jenny a few times today

Comments:

- It would be more natural to use the present perfect in the first example at some point during the day

- The past simple version might be used at night when looking back upon the day as past

2)

Present perfect simple: Betty’s called me twice this afternoon

Past simple: Betty called me twice this afternoon

Comments:

- It would be more natural to use the present perfect in the first example at some point during the afternoon

- The past simple version might be used later on in the day i.e. in the evening or at night

My argument remains that the present perfect is the most difficult English tense to master because the learner often has to juggle between two timespans. To borrow terminology favoured by Declerck (1991: 19), these time spans are the “past-time sphere” (past sector) and the “pre-present sector” (i.e. the portion of the present time-sphere that is anterior to the moment of speaking).

News broadcasts - Another spanner in the works

Paul Rastall (1999: 80) provides some examples from BBC news broadcasts whereby the present perfect is combined with adverbials of ‘finished time’ when a past simple may be expected:

At the hospital in Kinshasa staff have been paid just once last year.

The first snows have fallen several weeks ago.

Manchester United have gone back to the top of the Premier Division by beating West Ham 2-1 earlier today.

There has been an accident on the M1 earlier this morning and delays are expected.

The strike by Israeli refuse workers has been called off on Sunday.

Feasibly, I could have included this part on news broadcasts in the previous section on ‘current relevance’. As Rastall (1999: 81) notes:

The criterion of `current relevance' to the moment of speaking is quite evident in all of the cases adduced, but in each case the speaker also wishes to convey the point in time when the past event occurred.

Hence, we would normally expect a past simple verb form in the cases above. However, the newsworthiness of the information surpasses the need to include a past simple verb form.

As Rastall (1999: 81) neatly summarises:

Here is an example of a pragmatic consideration overcoming a grammatical convention.

(b) Just and ever - two adverbs which magnify the British vs. American English debate

It’s possible to use the word just in conjunction with both the present perfect and past simple to refer to the immediate past. There is no difference in meaning between the two tenses:

He has just arrived.

He just arrived.

According to Walker (1967: 18) A further example of this overlap between the past simple and the present perfect simple with no change in meaning is found in the relative clause succeeding a superlative in the presence of the word ever:

That’s the most beautiful sunrise I’ve ever seen.

That’s the most beautiful sunset I ever saw.

When other time indicators in the present time frame are used in this construction, we use the present perfect simple:

This is the best film I’ve seen in years.

This is the first time I’ve visited this city.

Things get messy when you factor in British and American varieties of English. With regard to He just arrived and That’s the most beautiful sunset I ever saw, a teacher of English from Britain may dismiss such utterances as ‘wrong’. American teachers of English would tend to accept them.

(c) The case of already

Already is more commonly used with the present perfect tense than the past simple.

However, this adverb is also used with the past simple of the verb to be (occasionally with the past of other verbs) when the accompanying time expression - most often a clause - denotes an action prior to the action in the main clause:

Jane was already exhausted when she started working.

John was already there when I arrived.

I already knew that before you told me.

(d) The past simple without past time indicators

The average English language student might have been duped by course materials into thinking that the simple past tense must be accompanied by, or placed within, a past time indicator. However, as Walker (1967: 19) thoughtfully pointed out, this is not always the case. Take the following sentences, for example:

Shakespeare wrote comedies, histories and tragedies.

Why did you say that?

His leg is in a cast because he broke his ankle.

Columbus discovered America.

The most accomplished speaker of English automatically senses that these actions occurred at some point in the past. Nevertheless, the speaker does not include an adverbial since he’s not interested in the time.

I believe that many students would use the present perfect in the sentences above because this tense is often unaccompanied by a time indicator. As they may be so used to seeing the past simple verb forms coexisting with a past time indicator, they might be more inclined to say, for example, Why have you said that? instead of Why did you say that?

(e) A sequence of events - a use limited to the past simple

It’s relatively common for learners of English to try to use the present perfect when describing a chronological sequence of events. Nevertheless, it’s more appropriate to use the past simple:

So I went up to the kitchen on the second floor, got him a bowl of tomato soup, got him a sandwich and cup of hot chocolate, and brought everything down. I put his meal on the table and went off to do the washing.

The present perfect simple - A hard tense to acquire due to unhelpful grammar guides

In light of the arguments above, I can only conclude that there are far too many narrow-minded compilers of grammar guides. In the act of trying to simplify the present perfect tense, they unconsciously make it the most difficult English tense to learn through by providing so many baffling generalisations.

Frankly, it’s little wonder that fossilization in second language acquisition occurs and students cannot overcome the intermediate plateau when they’re overwhelmed with rules which are not as hard and fast as they appear to be.

References

Close, R.A. (1992). A Teachers’ Grammar: The central problems of English, Hove, UK: Heinle ELT

Comrie, B. (1985). Tense, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Declerck, R. (1991). Tense in English: Its structure and use in discourse, London: Routledge

Klein, W., The Present Perfect Puzzle, Language, Vol 68, No. 3 (Sep,. 1992), pp.525-552

Lester, M. (2012). Practice Makes Perfect: English Verb Tenses Up Close, New York: McGraw Hill

Parrott, M. (2000). Grammar for English Language Teachers, Second Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Rastall, P. (1999. Observations on the present perfect in English, World Englishes, Vol 18, No. 1, pp.79-83,

Swan, M. (2017). Practical English Usage, Fourth Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Walker, R.H. Teaching the Present perfect Tenses, TESOL Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Dec., 1967), pp. 17-30

Werner, V. (2014). The Present Perfect in World Englishes: Charting Unity and Diversity, Bamberg: Bamberg University Press