Natalie Braber | The Nottingham accent and East Midlands English

Another interview, another fascinating topic - the Nottingham accent and the defining features of East Midlands English.

My latest guest here on English Coach Online is Professor Natalie Braber. Natalie teaches in the School of Arts and Humanities at Nottingham Trent University within the subject area of Linguistics.

Her teaching responsibilities are mostly related to sociolinguistics, child language acquisition and psycholinguistics.

Natalie’s main interests are in the fields of sociolinguistics and language variation. Specific research interests include:

- Accents and dialects

- Language and identity

- ‘Pit Talk’ – language of East Midlands coal miners

After my recent post on the current state of accents and dialects in the UK, I contacted Natalie to see if she'd give an interview on accent and dialect in Nottingham, whether East Midlands English is essentially ‘northern’ or ‘southern’ in nature and the phenomenon known as ‘dialect levelling’.

I'm mightily glad that Natalie accepted my invitation.

Let's check out what Professor Braber had to say:

1. Let’s start with Nottingham, where I lived for four years - three in Clifton and one year in Sneinton.

Can you comment on any features which distinguish the Nottingham accent from, let's say, Derby, Leicester or Ilkeston accents?

“ When we think of the UK, we tend to think of the north and the south. People in the north say 'bath' using the short vowel sound 'a'.

Conversely, people in the south say ‘baath’, with the long ‘a’ vowel sound.* It’s not quite as straightforward as that, but most people interested in English accents and dialects tend to think there is this two-way division.

Unfortunately, linguists haven’t looked at the East Midlands as much. There are certain features that are definitely northern. However, there are also things that sound quite southern. Some researchers, such as Clive Upton, have said we need to think of a tripartite distinction. Maybe it needs to be North-Midlands-South. Other researchers simply believe that the Midlands is almost a no-man’s-land between the north and the south. Nobody really knows what’s happening.”

* Southern England long ‘a’ vowel sound in ‘bath’ - /bɑːθ/. It’s interesting here to refer to what is known as the ‘trap-bath split’. This is a vowel split that occurs primarily in southern accents in England. An isogloss runs across the Midlands from the Wash to the Welsh border, passing to the south of the cities of Birmingham and Leicester. North of the isogloss, the vowel in words such as ‘bath’ is usually the same short 'a' as in 'cat'. South of the isogloss, the vowel sound in words like ‘bath’ and ‘laugh’ is generally long.

Noticeable features of the Nottingham accent

“When it comes to the Nottingham accent, people are likely to speak with the northern short ‘a’ vowel sound, as in ‘bath’. We also hear people here say ‘bus’ with the ‘oo’ sound in ‘put’.* However, when people in Nottingham say a word such as ‘house’, it sounds more like ‘aaas’, which sounds much more southern to me.

There are also features of modern Nottingham speech which we don’t hear in recordings of older people. For instance, younger people might pronounce 'happy' as ‘happeh’. This can also be heard in areas of Manchester.

One more feature of Nottingham speech that’s come over from Leicester is the pronunciation of words ending in -er. Instead of pronouncing the ‘uh’ schwa at the end of words like Leicester, sister and brother, people in Nottingham might say ‘Leicestor’, ‘sistor’ and ‘brother’. This is something that’s quite new to the region.

Another distinctive quality of the Nottingham accent is h-dropping. People drop ‘h’s’ at the beginning of words. I gave a good example earlier with house - ‘aaas’.

There’s also a great deal of yod-dropping. So, a word like news is pronounced ‘news’ [nuːz] instead of ‘njews’ [/njuːz/]. Interestingly, people in East Anglia drop that yod sound before everything. As for people in Nottingham, they say words like ‘duke’, ‘tuna’ and ‘Stuart’ without the ‘y’ sound before the ‘u’ vowel.”

* Saying ‘bus’ in northern England - /bʊs/ - with a vowel sound similar to that in /pʊt/ (put)

2. Yorkshire dialect expert Dr Barrie Rhodes mentioned in an interview with the BBC that Yorkshire is “undergoing a process of levelling out” - that dialects are becoming more similar. What have you noticed in Nottingham and the broader East Midlands area when it comes to dialect levelling?

“It’s definitely changing. There’s always a fear that dialects are disappearing. I would say that there are certainly some dialects that are disappearing. Rural dialects might not sound as distinctive as they once did.

It’s safe to say that the Nottingham accent is vastly different to the speech you hear in Newcastle, Liverpool, Birmingham or London. However, there are certain characteristics that are definitely spreading.

I should mention something called th-fronting. Th-fronting is the pronunciation of the English "th" as "f". For instance, people might pronounce ‘three’ as ‘free’. This is a tendency that’s spreading northwards from the south-east of England. Th-fronting came to London quite some time ago and it seems to be jumping from city to city. Nottingham is certainly one of the places where it’s caught on. Nevertheless, th-fronting seems to have bypassed rural dialects.

Interestingly, our first year students have an exam where they have to transcribe words phonetically. It happens that, if we give them a word like ‘three’, some of them transcribe the ‘th’ with an ‘f’ sound and not a ‘th’ [/θ/] sound.

Dialect levelling also occurs with individual words. A word such as ‘like’ can have lots of different meanings. It can be a verb - I like language. ‘Like’ can also be used as a filler - I was, like, going out tonight. Many people now also use ‘like’ as a quotative - He was, like, I’m not going to that party.

That ‘like’ has come over to the UK from America, through TV and increased media coverage.

There’s a lot of quite negative discussion surrounding the word ‘like’. Many grammarians and sticklers for ‘proper’ English don’t like it when ‘like’ takes on a filler or quotative function. They might have a perception that young people can’t speak properly.

Most years I have a dissertation student who wants to look at the spread of ‘like’ in a particular group.

In the Nottingham accent and dialect, the pronoun system is quite interesting. You’ve got people saying things like ‘yoursen’ and ‘oursen’ instead of ‘yourself’ and ‘ourselves’.

There are differences in pronunciation between north and south Nottinghamshire. For example, people in north Notts might pronounce ‘water’ with the short ‘a’ vowel sound and ‘open’ as ‘oh.pen’ instead of ‘ow.pn’. However, I hear such forms less in younger speakers, so there are definitely changes happening.

Overall, there are still features of the Nottingham accent and the broader Notts dialect that make them distinctive to other areas. People here don’t sound like people from the West Midlands or other surrounding areas.”

3. Do you have any comments on gender variation in East Midlands accents?

“Generally, in linguistics, there’s this idea, certainly historically, that male speakers were more likely to be stronger dialect speakers than women. Paradoxically, women were more likely to sound closer to standard English.

We also find cases where, if you ask people about their language usage, women are more likely to overreport that they use standard English. In contrast, men are more likely to overreport that they use dialect forms.

People aren’t always very good at knowing what they do themselves. They often report doing what they think they would like to do, or what they think they should be doing.

Indeed, I did a study several years ago related to German. I investigated the use of two specific words. The interviewee was asked which of these two words they would use. The word that he said he would always use, he used once, and the word that he said he wouldn’t use, he actually used 99 times in an extended interview. So, people aren’t always very accurate at reflecting.

Yes, we do see gender differences, but I think there are other factors such as social class, upbringing, who’s around you and where you’re from that affect accent and dialect development much more.”

4. I’m from Wellingborough, Northamptonshire, which is in the southern part of the East Midlands. I presume that Northamptonshire is on the borderline between southern and northern accents. Do you hear traces of other East Midlands accents, for example, Leicester, when you hear me speak?

“The Northamptonshire question is interesting. We decided not to include Northampton in a book* that I published a few years ago on East Midlands English. Nor Lincolnshire in fact.

I did some work with people where I gave them maps and I asked them to say what they thought included the East Midlands. Northants was rarely included, even by people who lived there as well.

I certainly think that Northants speech has far more southern features than the rest of the East Midlands does.

Leicester’s a really interesting one as well. If you look at a map of the East Midlands, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire run side by side and you’ve got Leicestershire at the bottom. So, Leicester is definitely more southern than Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire.

Although the speakers from Leicester that I’ve recorded use many northern features, they’re still right at the southern edge of the northern dialect boundary. I cannot say they sound like northerners and I think the southern features still outweigh the northern features.

Listening to you, I hear far more southern features than I tend to hear in a Derbyshire or Nottinghamshire speaker.”

* Braber, N. and Robinson, J., 2018. East Midlands English, De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin

The counties of the East Midlands. Notice the county of Rutland to the north of Northants.

5. Sociolinguist, Peter Trudgill, stated that in traditional dialectology, the East Midlands area falls under ‘Central’ dialects, which come under the ‘Southern’ branch, but in modern dialectology, it falls in the ‘Northern’ category. What is your opinion on this dichotomy?

“On the whole, people in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire associate themselves far more with the North than the South. People in Leicestershire generally don’t feel as strongly connected to the North.

There are features of East Midlands speech which are quite northern so I think it groups more easily with northern. Maybe we need a separate ‘Middle’ section.

In so many countries - such as France and Germany - there’s always talk of north-south. But what about east-west? The East Midlands is very different to the West Midlands. However, nobody talks about an east-west distinction.

In a language perception study I did with 17 and 18 year-olds, they were very quick to say that “that’s not us” when they listened to the West Midlands recording. Geographically, the West Midlands was close to them. However, they didn’t want to be associated with West Midlands speech patterns.”

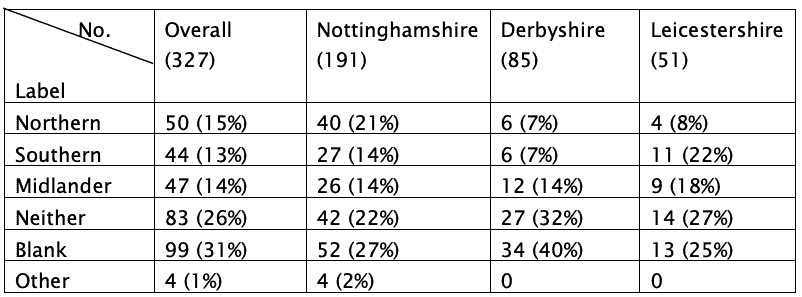

6. I’ve read your paper The concept of identity in the East Midlands of England. Essentially, you aimed to investigate where a group of East Midlands students (around 17-18 years old) believe the North/South divide to fall in the UK and whether they considered themselves to be ‘Northerners’ or ‘Southerners’, or as something else. What’s your opinion on where the North/South boundary lies in the UK?

“The thing that was interesting about that paper was when I asked the students to draw the North/South divide, if they thought there was one, 99% of them drew a line.

Then, I gave them another question, asking them whether they considered themselves to be a northerner or a southerner. Frankly, I didn’t want to feed in the word ‘Midlander’ because I wanted to see if they’d come up with the term themselves. So they could choose between ‘northerner’, ‘southerner’ or ‘something else’.

Here’s the interesting part. 99% of the entire surveyed group said there is a distinction. However, when I asked them about their identity, i.e. southern, northern or ‘something else’, for most of the groups almost 50% either said they didn’t know or ‘something else’. A small proportion of people defined themselves as ‘Midlander’. The Derby group were saying ‘Midlander’ more than anyone else. As for the Leicester group, they were saying ‘southern’ more than ‘northern’. The Nottingham group were saying ‘northern’ more than ‘southern’.

So, overall, there are clear differences within the East Midlands region when it comes to the concept of identity. People admit to there being a north-south divide but they don’t quite know where they fit in it. As I said in the previous question, perhaps it should be: North - Midlands - South.”

Results from Braber's 2014 paper 'The concept of identity in the East Midlands of England'. The figures show whether the students considered themselves to be Northern/Southern/Neither. Some students independently wrote other labels, such as 'Midlander'.

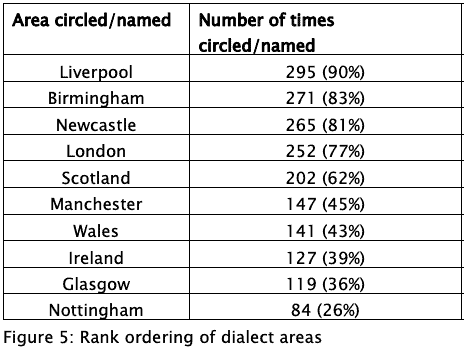

7. Now, let’s move on to your paper Language perception in the East Midlands in England. Essentially, you asked 327 A-level students (17-18 years old) from Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to distinguish local speech patterns from speech patterns from other regions. It’s easy for us to recognise a Liverpool or Birmingham accent. But why was it that participants were unable to situate local voices accurately?

“There are several reasons I think. People are often not aware that they have an accent until they leave the area that they’re from. Often, the way that people sound is like the people around them so they don’t really think that they have an accent. That is, until they go away to university or move to work in another city.

If you asked someone what people from Liverpool, or Newcastle, or London sound like, then the neutral would have a good go at imitating these accents because there’s always been a lot of exposure to them in the media. If you think of comedians as well as TV and radio presenters - those areas are covered. How often do you hear the Nottingham accent on TV? And if I asked you to name a famous celebrity from the East Midlands, could you name one?*

People don’t have much experience of hearing East Midlands accents. Gary Lineker’s from Leicester. He doesn’t sound very local.

Just to return to the project in question where students listened to recordings of various UK accents so they could try to name the different accent areas they heard. When I started the project, Wales didn’t feature very highly. However, by the end of the project, it did. TV sitcoms like Gavin and Stacey increased people’s awareness and recognition of varieties that they might not have heard that much before.

If you asked somebody from London or Scotland to imitate someone from the East Midlands, they wouldn’t know what to do.”

* I did hesitate when Natalie asked me to name a famous celebrity from the East Midlands. In the end, I said snooker player Mark Selby. Although, with the greatest of respect to 'The Jester from Leicester', he's hardly a celebrity.

The rank ordering of the ten most frequently named/circled dialect areas in Braber's 2015 study 'Language Perception in the East Midlands in England'.

8. Moving on to your co-authored article FOOT-fronting and FOOT-STRUT-splitting: vowel variation in the East Midlands. When it comes to the acoustic properties of the words ‘foot’ and ‘strut’ in Leicestershire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, your observation that the overlap between ‘foot’ and ‘strut’ is higher in Leicestershire than in Nottinghamshire came as a surprise to you. After all, Nottinghamshire is located further north than Leicestershire. What other surprises emerged from this study?

“As we wrote in the paper, this area of research needs more work. We only dealt with a small sample of speakers.

In the North, the vowel sound in FOOT and STRUT is the same. It’s different in the South. But Sandra Jansen and I were interested in what happens in the East Midlands. We wondered whether people would use some of the forms some of the time and other forms at other times. Or, as we predicted beforehand, would the participants produce a vowel that’s midway in between the words FOOT and STRUT?

Actually, our prediction didn’t bear fruit. For the people that we looked at in the East Midlands, both FOOT and STRUT varied slightly but not in the way we had anticipated.”

Key takeaways from the study:

- The realisation of FOOT and STRUT in the East Midlands is rather variable, with most speakers showing very high rates of overlap

- Speakers of both age groups in Derbyshire showed more overlap between FOOT and STRUT than in Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire

References:

JANSEN, S. and BRABER, N., 2021. FOOT-fronting and FOOT–STRUT splitting: vowel variation in the East Midlands. English Language and Linguistics, 25 (4), pp. 767-797. ISSN 1360-6743

BRABER, N., 2015. Language perception in the East Midlands in England. English Today, 31 (1), pp. 16-26. ISSN 0266-0784

BRABER, N., 2014. The concept of identity in the East Midlands of England. English Today, 30 (02), pp. 3-10. ISSN 0266-0784