Proposing a spoken English syllabus for intermediate level secondary school students

In this post, I propose a spoken english syllabus for intermediate level secondary school students in Poland.

My suggestions mostly stem from many years of experience teaching English to Polish learners. In this post, I urge syllabus writers to revise their obsession with a grammatical syllabus. Moreover, I question whether there is an ideal order for teaching English tenses and aspects to secondary school students. I also consider the state of English language teaching in Polish state schools, analysing a typical syllabus along the way. Finally, I come up with a draft of a spoken English syllabus for intermediate level secondary school students.

WHAT ARE THE MAIN ISSUES WITH CURRENT ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE SYLLABUSES IN POLAND?

When I Googled “program nauczania języka angielskiego” (teaching programme/syllabus for the English language) just recently, alarm bells sounded immediately.

Essentially, major ELT publishers seem to be influencing the preparation of English language syllabuses for primary and secondary schools in Poland. These publishers include Macmillan, Pearson and Oxford University Press.

So, let’s analyse the situation:

Do publishing houses and syllabus writers contrive to 'fix' syllabuses to merely suit the content in major publishers’ coursebooks? Or, have we got coursebook and syllabus writers who are aware of the grave issues Polish students of English face?

I suspect you know which side of the fence I am on.

I’ve just browsed a 110-page syllabus for both a “four-year general secondary school and five-year technical secondary school”. Yes, you read it correctly. 110 pages. I bet that these syllabus writers like the sound of their own voices.

Look, these syllabus writers do have some honourable intentions and make the occasional good point. For example, they encourage teachers to familiarise students with language learning strategies, such as guessing the meaning of words from context. Unfortunately, teachers haven’t got much time to help students with developing their language learning strategies. This is because they have to teach so much grammar and vocabulary so students can just 'pass the test'.

The syllabus writers also go into great depth about humanistic teaching approaches. I think that overworked teachers might have too many other things on their minds to be 'humanistic'.

I guess that syllabus writers’ compliance with tradition and the grammatical syllabus is understandable. Secondary school language teaching is all about teaching to the test. Therefore, syllabus writers and the Ministry of Education don’t care about what natural spoken English actually consists of. Why would they bother about referring to authentic English conversations, corpora and scrutinising the major patterns of use in spoken and written registers? In sum, the easy way out for syllabus writing pen-pushers is to include everything under the sun in their syllabuses.

WHAT DOES A TYPICAL SPOKEN ENGLISH language SYLLABUS FOR INTERMEDIATE LEARNERS IN POLISH STATE SECONDARY SCHOOLS LOOK LIKE?

As expected, the 110-page syllabus I’ve analysed is excessively dense when it comes to vocabulary and grammar.

Let’s analyse the role of vocabulary and grammar in this syllabus, and then consider some other prominent features:

VOCABULARY

For both basic and advanced levels, vocabulary topics are broken down into 14 sections. Some of these topics include Education, Work, Health and Sport.

The syllabus writers offer examples of subtopics which comprise these sections. For instance, for Health, teachers can go into well-being, diseases, addiction and emergency first-aid procedures.

So many of the suggested sub-topics would be so far beyond secondary school pupils’ interests. For example, outer space and buying apartments are hardly pressing concerns for most teenagers. Certainly, they won’t purchase any apartments using the English language while they’re at school in Poland. Hence, such pointless lexis passes to the short-term memory and is forgotten in the blink of an eye.

Across four or five years of secondary and technical school, students have so many opportunities to encounter incidental vocabulary acquisition. Incidental vocabulary acquisition refers to the way in which students 'pick up' new words when they’re immersed in a task. Therefore, incidental acquisition operates contrary to the conscious memorisation of words. With this in mind, do teenagers really need to purposely memorise so much vocabulary related to so many topics?

GRAMMAR

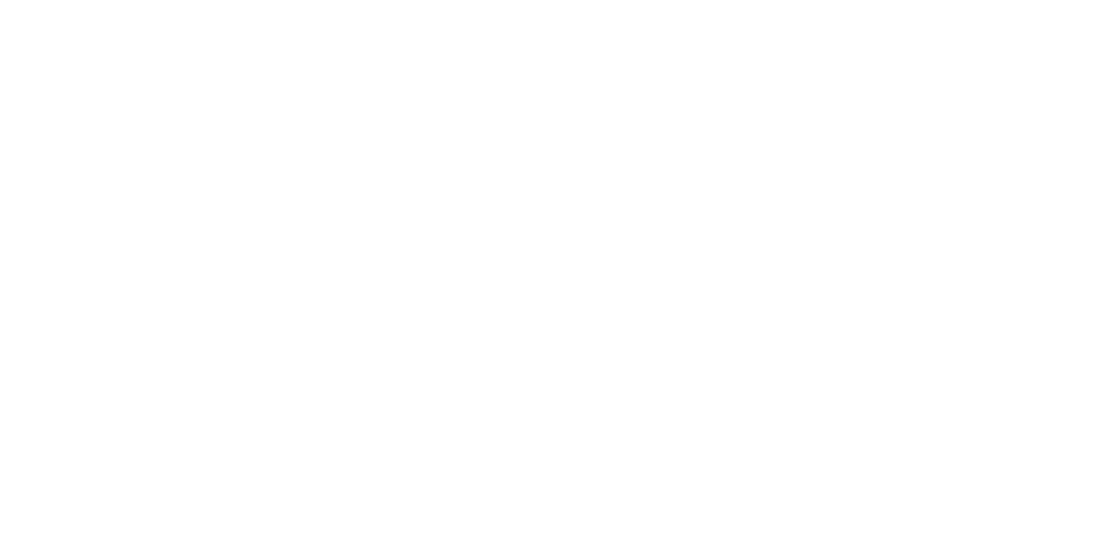

There must be around 100 separate grammar points in this syllabus.

It seems to me that these syllabus writers came up with a linear grammatical syllabus. In other words, all of the supposedly easy structures are lumped together at the beginning. For example, we have the verbs be and have (got). Soon after, we have there is and there are. When it comes to tenses, we see the same old predictable order that grammatical syllabuses and coursebooks swear by:

COMPARING TENSE ASPECTS LEADS TO CONFUSION

In this syllabus, “porównanie czasów teraźniejszych” means “comparing the present tense aspects” (simple and continuous). These students have been through all that in the previous eight years of their lives. So why confuse them for another four or five years?

If this were my syllabus, I’d write PRESENT SIMPLE - ONLY THE PRESENT SIMPLE. In big bold size 20 font.

Polish students of English overuse the present continuous tense. Therefore, I wouldn’t include it in any primary, secondary or sixth-form syllabus. Besides, so few interactions in English actually take place in the present continuous. Anyway, I have written about the pitfalls of teaching the present simple and present continuous tenses so do check out that post.

LET'S HAVE A SLIMMED DOWN SYLLABUS PLEASE

Further down the list, the syllabus writers recommend teachers to compare the Future Continuous vs. Future Perfect vs Future Perfect Continuous. I’m not sure I’ve used any of these tenses more than five times in my life. Let’s delete them from the syllabus.

Then, we come to the passive voice (strona bierna). Unless students plan to do lots of formal writing in their lives, the passive voice is another weird fascination among syllabus writers. It’s hardly used in spoken English. Frankly, getting teachers to lecture on the past perfect passive is nothing short of a joke. I’ve never used it in my life and never will.

These syllabus writers also included the explicit teaching of articles (the, a) and prepositions. I’ve been there, done that and it doesn’t work. Learners don’t respond to rules and gap fill exercises. In my view, learners have to start recording their own speech and working with the teacher to analyse what’s going wrong. Continuous awareness-raising reaps more rewards than doing gap fill exercises.

IS THERE AN IDEAL ORDER FOR TEACHING ENGLISH TENSES AND ASPECTS TO SECONDARY SCHOOL STUDENTS?

I’ve never been one for ordering tense aspects according to their apparent level of difficulty.

Given that the verb be and the present simple usually appear at the beginning of a grammatical syllabus, teachers naively believe that these are the easiest tenses for students to learn. In my experience, Polish learners of English have grave problems with producing the present simple when called upon. They particularly struggle with producing the third person singular -s form when called upon.

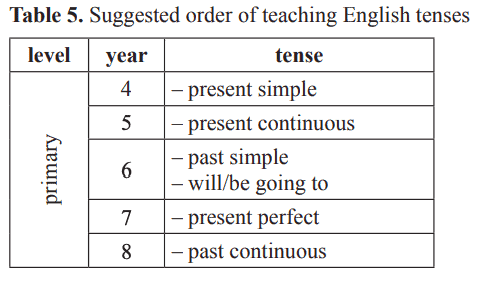

In terms of giving pupils a chance to acquire the present simple, it doesn’t help that teachers have to cram in the teaching of so many tense aspects across an academic year. In his paper, A possible order of teaching English tenses in primary school, Croatian English language lecturer, Jakob Patekar, hits many nails on the head concerning grammar instruction. For instance, he doesn’t advocate the teaching of a whole batch of tenses in a single academic year. As Patekar writes: “Having spent two years exploring two present tenses, we believe that in year 6 students are ready to move to the past simple.”

Patekar also aims to draw readers’ attention to the Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English (LGSWE) and its own corpus (the LSWE Corpus). The LGSWE offers its readers insight into statistical data regarding the frequency of a given grammar point. This data pertains to four registers: conversation, fiction, news and academic. Hence, I believe we should be looking towards the frequency of tenses, as opposed to how 'easy' they are, when it comes to creating a spoken English syllabus for intermediate secondary school students.

Overall, our schools need more people like Mr Patekar to stand up to this craze for cramming so many tenses into a single academic year. Personally, I don’t believe that an ideal order for teaching tenses exists. However, the evidence from corpora suggests that the present simple, past simple and present perfect tenses require sustained exposure over a number of years. Let’s move on to that topic now.

THE LONGMAN STUDENT GRAMMAR OF SPOKEN AND WRITTEN ENGLISH: EVIDENCE THAT THE PRESENT SIMPLE SHOULD HAVE CLEAR PRECEDENCE OVER THE PRESENT CONTINUOUS

So, I managed to get my hands on copies of the LGSWE and the Longman Student Grammar of Spoken and Written English (SGSWE). The latter is aimed at advanced students of English.

For now, I wish to focus on the conversations/spoken English that the writers of the LGSWE consulted in the LSWE corpus. Above all, I’m hunting for evidence to support my view that the present simple should dominate the (grammatical) English teaching landscape in Polish schools.

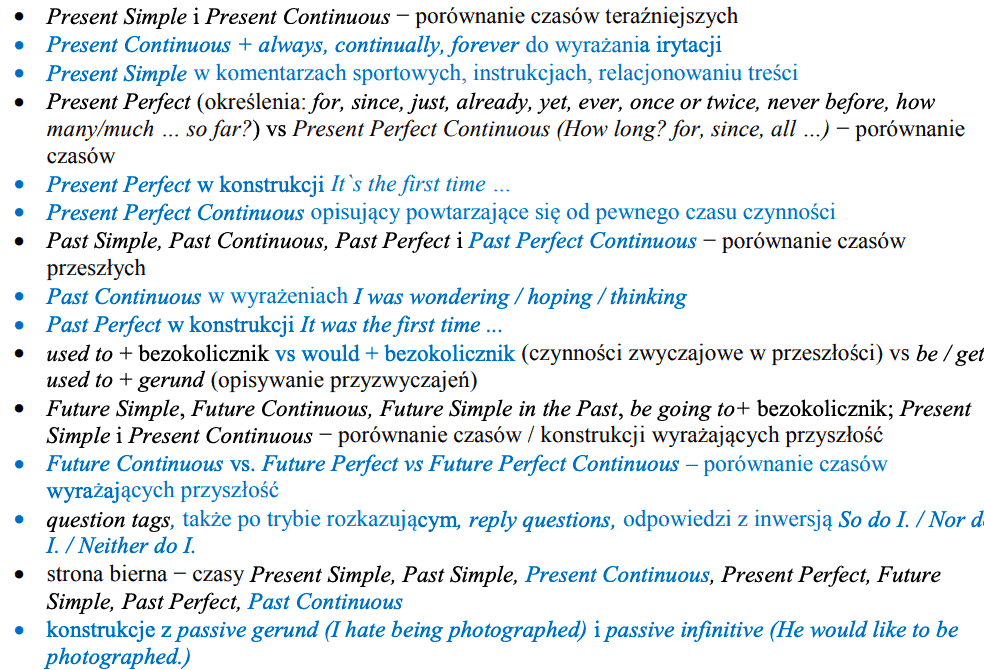

The table below refers to the frequency of simple, perfect and progressive aspect in four registers per million words:

Biber et al., 1999, Figure 6.2

As you can see, the simple aspect overshadows the other two aspects in the recorded samples of conversation.

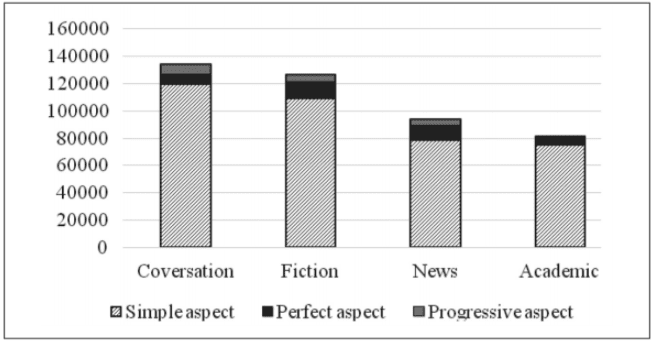

In the following table, notice that present tense verbs are more common than past tense verbs and modal verbs in conversation.

Biber et al., 2002, Figure 6.2

Overall, these tables present further compelling evidence for the need to emphasise the present simple in every spoken English syllabus for intermediate level secondary school children. Present tense verbs occur with a frequency of 100,000 words per one million words in the LSWE. I assume that the present continuous does not make up a significant proportion of the present tense category.

WHY SHOULD SYLLABUS WRITERS BROADLY OVERLOOK THE PROGRESSIVE ASPECT?

When it comes to the progressive (continuous) aspect, I’m not convinced of it’s inclusion in any spoken English syllabus for intermediate level pupils.

In my view, Patekar’s “suggested order of teaching English tenses” in Croatian primary schools (see below) wouldn’t cut it in Polish schools:

Personally, I’d scrap the teaching of the continuous aspect, especially the present continuous aspect. This is because Polish students of English rely excessively on the -ing phoneme. Consequently, the overteaching of 'I’m' and the -ing phoneme has created a wealth of fossilised errors, such as:

- I’m making a cake yesterday (we need the past simple “I made”)

- She's going to the gym every day (we need the present simple “She goes”)

- I’m play football (we need "I" before a bare infinitive = "I play")

People often use verbs with the continuous aspect to refer to:

- Activities and physical events - starve, shop, bleed, rain

- Communication acts - chat, joke, moan, talk, scream

- Mental/attitudinal states or activities - look forward, hope, wonder, think

- Perceptual states and situations - feel, watch, listen, look

- Static physical situations - wait, sit, stand, stay, wear

The present continuous has such a TEMPORARY, short-lived role in conversation. Indeed, people may use the present continuous to get something off their chest at the start of a conversation. For example, “I’m looking forward to going to Greece”. Or perhaps, “It’s raining here”. However, entire conversations never revolve around the present continuous in the same way they do around the simple aspect.

WHICH LEXICAL VERBS SHOULD A SPOKEN ENGLISH SYLLABUS FOR INTERMEDIATE LEARNERS PAY THE MOST ATTENTION TO?

Any spoken English syllabus for intermediate level learners needs to pay heed to lexical verbs, such as get, eat and go.

So, let’s take a closer look at what lexical verbs are all about:

WHAT IS A LEXICAL VERB?

Otherwise known as ‘full verbs’, lexical verbs function only as main verbs in a sentence. Examples of lexical verbs include run, go and think.

Lexical verbs often occur as multi-word units. For instance, the phrasal verb look at in “I looked at the job applications in two batches” is a multi-word unit.

WHAT ARE THE VARIOUS SEMANTIC CATEGORIES OF LEXICAL VERBS?

According to the SGSWE, it’s useful to distinguish between seven semantic categories of lexical verbs. These are activity verbs, communication verbs, mental verbs, causative verbs, verbs of occurrence, verbs of existence or relationship, and verbs of aspect. Let’s have a look these in a little more detail:

A. ACTIVITY VERBS

Activity verbs refer to intentional actions. The most commonly used verbs in English are activity verbs. Among the most common activity verbs across the four registers are buy, get, give, go and make.

B. COMMUNICATION VERBS

Ask, talk, call, say, tell, speak, write

C. MENTAL VERBS

Mental verbs refer to mental states or processes, as well emotions, perceptions, desires and attitudes. Some of the most common ‘mental’ verbs are like, love, see, think, suppose and feel.

D. CAUSATIVE VERBS

Causative verbs denote that someone or something helps to create a new state of affairs. There are only a few common causative verbs, including allow, help, let and require.

E. VERBS OF OCCURRENCE

Verbs of occurrence report events that occur without the intervention of an actor. The event that the verb describes often affects the subjects of these verbs. In this example, there would be a visible impact on the underlined subject here:

* The lights changed

F. VERBS OF EXISTENCE AND RELATIONSHIP

Exist, seem, appear, stay, live

G. VERBS OF ASPECT

Verbs of aspect signify the stage of progress of an activity or event. Common examples include keep, start, stop, continue and begin.

WHAT ARE THE MOST COMMON LEXICAL VERBS?

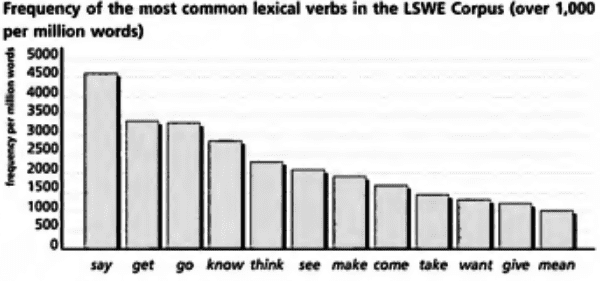

Eleven of the twelve most common lexical verbs in English are mental or activity verbs. The only exception is the verb say, which is the most common lexical verb overall:

According to the LSWE, the verb get is the second most common in conversation. Get is an extraordinarily versatile verb. Although it’s often used as an activity verb, it also acts as a causative verb and verb of existence in a range of contexts. Finally, get occurs in idiomatic multi-word phrases, such as get rid of and get away with.

All in all, every spoken English syllabus for intermediate level learners should devote significant attention to lexical verbs such as get, think and go. A teacher should spend weeks or months presenting real extracts from conversation and corpora to students in order for them to appreciate these lexical verbs.

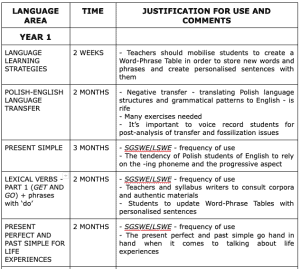

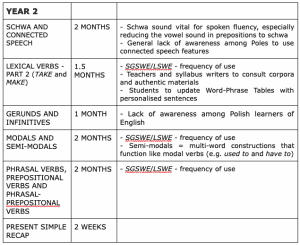

A MODEL SPOKEN ENGLISH SYLLABUS FOR INTERMEDIATE LEARNERS

What I present below is a model spoken English syllabus for intermediate learners at Polish secondary schools. This two-year syllabus is suitable for fifteen and sixteen-year-old students of English.

First of all, this syllabus aims to focus on the areas of English which Polish students of English struggle with the most. Secondly, the SGSWE has been instrumental when it comes to the syllabus's heavy lexico-grammatical emphasis.

Let’s check out my proposals:

COMMENTS ON THE SYLLABUS

Syllabus writers in Poland should focus on studying corpora and recommending authentic materials to teachers which they can exploit in the classroom. Film scripts, speeches (e.g. TED talks) and recorded conversations between native speakers would be a good place to start.

Another point is that spoken fluency is not all about grammar and lexis. The schwa sound is another key element of fluent speech. This is especially the case when it comes to reducing the vowel sound in prepositions to schwa. With this unstressed vowel sound in place, speech flows more naturally and quickly.

Final THOUGHTS

I’ve only begun to scratch the surface here. My main aims have been to inform teachers and syllabus writers that vocabulary and grammar learning should go hand in hand. Consider how certain lexical verbs commonly occur with certain grammatical structures. For example, the verbs seem and want are typically followed by a to-clause. We need to realise that vocabulary and grammar co-exist.

Traditional grammatical syllabuses impede students’ levels of spoken English. Eventually, students get stuck at the 'intermediate plateau'. They can’t break out of it because they lack knowledge of language learning strategies, and their errors have become fossilised. Finally, many Polish students' of English speech lacks variety. This is why I propose the deep learning of phrasal verbs, common lexical verbs (get) and other multi-word units.

My hope is that my proposed syllabus would begin to reverse the impact of crosslinguistic influence, otherwise known as negative language transfer. Negative transfer is when speakers transfer structures and language items from their first language into a second language. I don’t expect miracles. I just ask for teachers to provide Polish students with more opportunities to 'think in English'.

References:

Biber, D,. et al. 1999. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English, Pearson Education Limited: Harlow

Biber, D,. et al. 2002. Longman Student Grammar of Spoken and Written English, Pearson Education Limited: Harlow

Patekar, J. 2016. ‘A Possible Order of Teaching English Tenses in Primary School’, METODIČKI OGLEDI, 23 (2016) 1, 65–86