Teaching English to Refugees – with Zoha Seddighi

The idea to conduct an interview with an English language instructor engaged in teaching English to refugees came to me after connecting with Zoha Seddighi on LinkedIn.

Getting to know Zoha Seddighi

Zoha Seddighi is a certified teacher with an M.A. in English Literature from Macquarie University in Australia. She’s taught at universities, colleges and schools in Australia, Indonesia, Russia, Iran, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. As a humanitarian, Ms Seddighi has cooperated with the UN, AIESEC, UNICEF, UNESCO and The Alliance for International Women’s Rights.

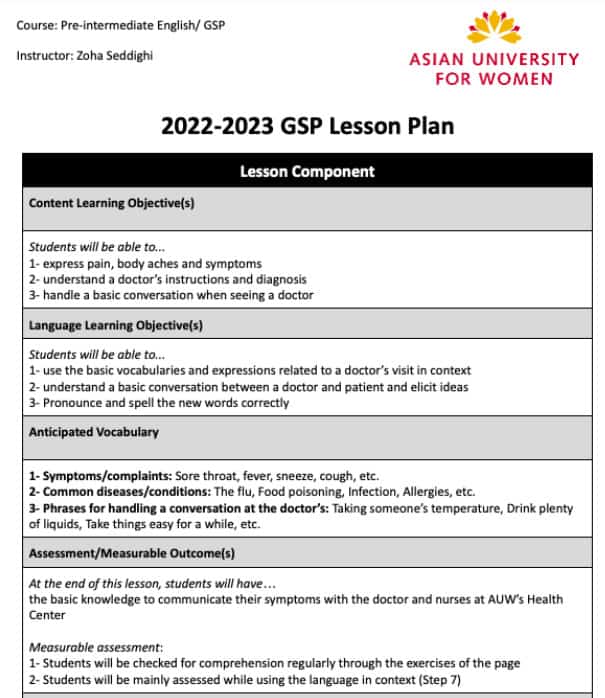

Ms Seddighi joined the Asian University for Women in Chattogram, Bangladesh, as an English Language Instructor in January 2022. She teaches the General Studies Program which has welcomed refugee girls directly from the Kutupalong refugee camp. The mission of the Program is to prepare young adults for higher education. Besides teaching English, Ms Seddighi empowers girls to become future leaders and make positive changes in their communities.

Interview with Zoha Seddighi - Teaching English to refugees

1. When you plan lessons for refugee learners, do you just have linguistic learning aims in your mind? Isn’t teaching English to refugees more about providing an escape for them, for example, fostering an environment which enables them to talk about typical daily experiences in the new country?

“I think it’s a mix of both - a linguistic focus and a safe environment for them to open up. We not only focus on English for resilience skills, but also their academic skills for higher education.

When I’m designing a lesson plan, I’m thinking about the context - my audience. Frankly, these classes are a way for students to express themselves and to find themselves in the class.

When teaching English to refugees, it’s vital for the instructor to create a bond and earn the students’ trust.”

Lesson idea for refugee students

2. What about designing an English language course for refugees - does the functional-notional syllabus feature heavily? Or perhaps the grammatical syllabus reigns supreme?

“I have to stick to a very clear syllabus. However, there is some scope to be flexible and spontaneous. Overall, I’d say my schedule is roughly 70% fixed.

When it comes to teaching English to refugees, I do think teachers need to have a very clear outline. Refugees respond very well to routine. They have a clear sense of purpose when they know what to expect the following week. I guess they feel they need to have something predictable and less chaotic in their lives.

As for the other 30%, I leave room for self-expression. What’s more, I may need to adapt or change material in the book I’m teaching from. I sometimes need to respond to the mood of the class, for example, by including a game or additional activity.

I remember one session where my students wanted to go outside and play a game. Frankly, I didn’t expect such a request from young adults. But ok - I said let’s go out for an hour. It was wonderful because they felt very much refreshed for the next hour of the class. It’s vital to give refugee students some time to release any negative energy they may be harbouring inside of them.

Additionally, I leave enough room for reinforcement and repetition. Our students have had major educational gaps in their education, so it’s a challenge for them to study English intensively. To ease the process, I include various activities and exercises to instill knowledge.”

3. How would you describe your relationship with your refugee students? Would you say you have to create more of a friendship with them compared with regular EFL students?

“I’ve been teaching English for ten years. During that time, I’ve worked with many different groups of students.

When I compare teaching English to refugees to other students I’ve taught, it’s a very different relationship.

When it comes to refugees, I need to spend a lot of time establishing a relationship with them. This relationship has to be very strong because if they don’t trust me, if they don’t feel safe in the class, they wouldn’t want to learn or work with me.

I spend time getting to know each person so that I can understand my class even better. Of course, I would need to create a strong bond with EFL students as well. However, it requires a lot more work and emotional investment with refugees.

In my experience, if an instructor doesn’t establish a strong bond and gain the trust of refugees, they wouldn’t contribute anything in class or would be simply loath to answer any questions at all.

In my previous positions, I just started teaching and my students automatically trusted me. Now, I have to really show my students that I care about them. You have to genuinely care because these students would see through artificial behaviour. Maybe I've changed as well. I’m more expressive. I use words and gestures to show them that they’re important to me.”

Zoha on a roll with refugee students

4. I guess that many of your students spend a great deal of time waiting in queues and being questioned or interrogated. Given they are used to having people constantly exerting their authority over them, how vulnerable do they feel to the inherent power dynamic of teacher and student?

“They do feel vulnerable. There are so many things in their everyday life that trigger their trauma or remind them of their status as refugees.

I’ve got to know them very well and I know what hurts them. Some people talk to them in ways I don’t approve of. They often share stories of how some students have bullied them or it comes to light that they’ve perhaps been treated differently than other students.

So, they bring all these feelings to class. I need to make sure that when they enter the classroom, it’s just about us - having a bit of fun, learning together and helping them become the people they want to be. Perhaps most crucially, I help them to use language as a resilient tool - a tool to help them be able to come across to others more convincingly and defend themselves when need be.”

5. Are you still very much in touch with your previous students at the university?

“Well, perhaps I can give you an example. I’m still in touch with my students from previous semesters. They do come to my office sometimes and ask for help with their writing or a troublesome grammar point. That’s when I can offer some additional instruction. It’s not a lot of work. Rather, it’s a matter of them having someone they can go to who they can trust.

All in all, I think everything revolves around maintaining that strong relationship we’d established many months before.”

6. Can you share a few more details about your role as the pilot program you co-established in support of refugee education and female empowerment?

“There was this idea of bringing and welcoming Rohingya* refugees from the Kutupalong** refugee camp, which is one of the largest refugee camps in the world.

At the start, there was some disagreement because many of the families understandably didn’t want their daughters to be away from them. This is because child marriage is very common in refugee camps and they wanted to marry off their daughters. However, a lot of the students who came to the Asian University for Women from the camp wanted to receive an education. So it was down to the university, and the women themselves, to ensure the families that their daughters would be in a safe environment.

Initially, we held informal induction classes with these girls to get to know them better and to understand their needs, level of English and academic capabilities. Vitally, we got to know what their community’s like so we can adjust our programmes to their needs.

As for our teachers, we made sure that teachers welcomed the students, and were trained to respond to trauma and were able handle any unfamiliar situations.

When it comes to female empowerment, we want our students to become more independent, to understand themselves as women, and to let them know they have a voice. One of our goals has been focused on helping them to start thinking about their futures because they stopped dreaming in the camp due to all the unfortunate things that had happened to them there.

To reiterate, I gave these students a lot of opportunities to express themselves, particularly through projects where they could express their opinions. I also tried to change their mindset about the classroom environment and the learning process. They come from a background where they don’t question the teacher or don’t even ask any questions because they consider this as an attack on the teacher. It took a lot of time and effort to make them understand that it’s ok to ask if they don’t understand something. I also helped them realize that it’s normal to make mistakes and making mistakes does not come with any punishments. This change of mindset helped them to trust their learning journey and improve drastically.”

* Who are the Rohingya people?

The Rohingya people are a stateless Indo-Aryan ethnic group who chiefly follow Islam and reside in Rakhine State, Myanmar.

** Where is the Kutupalong refugee camp?

Kutupalong is located in the Bangladeshi coastal district of Cox's Bazar. As a so-called mega camp, Kutupalong is home to around a million predominantly Rohingya refugees who escaped violent religious and ethnic persecution in neighbouring Myanmar.

7. Would you say you’ve found your vocation teaching English to refugees?

“When I looked at the job description for this role at the Asian University for Women, I thought to myself - this is me. I knew that I could do something for these girls, to empower them, to show that I care.

Concerning teaching English to refugees and providing education to underprivileged communities in general, a lot of instructors either don’t care enough or don’t have the stamina nor will to stay with these students.

One of my strengths is that I can take the time to get to know each person. When it comes to refugee education, I don’t like the checklist that you have to conduct yourself and teach in a predetermined way. Despite all the issues they have, refugees can contribute so much to this world.

Contrary to the media’s representations of refugees, these are people with feelings and emotions. A lot of my students are depressed. They have a hard time getting up in the morning just to come to class. I want them to know that there’s a teacher who’s not going to give up on them and who will accept them for who they are. Now the words ‘calling’ and ‘vocation’ are relevant - because so many people give up on them.”

Wrapping things up

Interviewing Zoha and writing up this post over the past few days, I can’t help but recall the four consecutive summers I spent in Southampton, UK, preparing predominantly Chinese students for their undergraduate programmes.

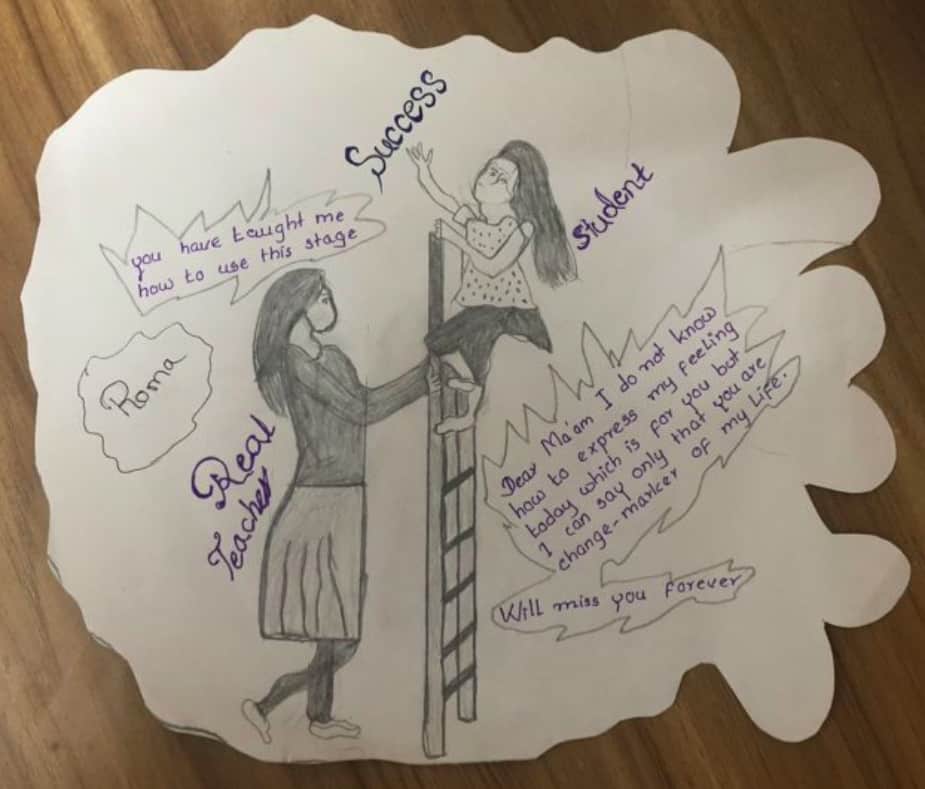

Sure, those young and hardworking Chinese adults weren’t refugees, and I’m not comparing pre-sessional work to teaching refugees. However, the roles of teacher to refugees and pre-sessional tutor are both what I would call ‘change-making’.

I was struck by one of Zoha’s posts on LinkedIn. Imagine being told “you are the change-maker of my life”: