Comprehensible Input Strategies: The Compelling Input Hypothesis

Comprehensible input strategies - a theme that popped up out of the blue when I discovered an article by Stephen Krashen called The Compelling (not just interesting) Input Hypothesis.

Most of you ELT buffs should have come across Krashen’s Comprehensible Input Hypothesis.

Essentially, Krashen argues that learners achieve fluency by gaining exposure to language in ways that makes it understandable to them.

With comprehensible input, learners don’t have to understand all of the words and structures in a given text or piece of listening material. Nevertheless, they still have to be able to understand key messages.

For Krashen, language acquisition occurs when input is only slightly more advanced than a learner’s actual level.

Gaining a greater level of comprehension comes about through rereading materials and listening to material again. Naturally, looking up new words and phrases is a key element of the comprehensible input hypothesis.

One of the most prudent comprehensible input strategies teachers can deploy to get the most out of their students is to share compelling input with them.

When input is compelling, a state of “flow” or being “in the zone” ensues.

Hence, my dear readers, the topic of this post is - The Compelling (not just interesting) Input Hypothesis.

It’s another one of Krashen’s admirable hypotheses.

The Compelling (not just interesting) input Hypothesis

In order for language acquirers to be able to focus on the input, it has to be interesting.

However, according to Krashen (2011), interest alone may not pave the way for optimal language acquisition:

It may be the case that input needs to be not just interesting but compelling

An interesting notion put forward by Krashen (2011) is that compelling input seemingly eradicates the need for motivation. That is, a conscious desire to get better. When learners receive compelling input, they acquire language irrespective of whether they're intent on improving or not.

HOW TO MAXIMISE LEVELS OF INTEREST AND COMPREHENSIBILITY

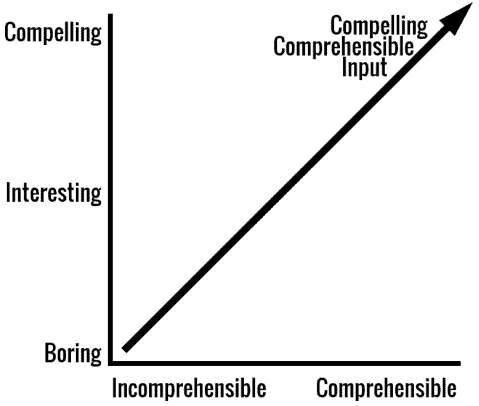

To create more compelling comprehensible input, we need to consider two key parameters: interest and comprehensibility.

The graph below ably shows how these two constructs should interact with each other:

Source: https://beyondlanguagelearning.com/2019/04/26/abundant-compelling-comprehensible-input-what-were-aiming-for-and-how-to-get-there

Hence, levels of interest range from boring to interesting to compelling. Comprehensibility varies from incomprehensible to comprehensible.

Ideally, learners should receive input that rates highly on both axes, i.e. highly compelling and highly comprehensible input.

Let’s consider some examples of input that characterise the four quadrants on this graph:

Boring and incomprehensible input

“Traditional” language teaching is exemplified by bizarre and meaningless repetition drills, complex grammatical explanations given in the L2, the teaching of rules and the audio-lingual method. Certainly, traditional methods do not create the right conditions for acquisition to occur.

With repetition drills, students often hear and repeat things they don’t comprehend. Even if they do understand, they still find the methodology tedious and soul-destroying.

Boring and comprehensible input

Again, this refers to “traditional” language teaching which exploits grammar-translation and drilling.

The difference is that the language teacher is able to use non-verbal communication to make the language comprehensible. Examples of non-verbal communication include pictures or explanations in the L1 (translation).

Perhaps most famously, the Rosetta Stone app revolves around matching words or phrases in the L2 to pictures.

Typically, Krashen (2013) had something to say about Rosetta Stone in a piece he wrote for the International Journal of Foreign Language Education.

In his critique, Krashen commented that “Rosetta Stone presents a tepid version of comprehensible input…” He concedes that Rosetta Stone “does indeed present comprehensible input….” However, in the samples he studied, “the input is not very interesting, and a long way from compelling ...”

Indeed, many of the pictures on Rosetta Stone relate to sentences that no sane person would ever utter. Have you ever said “The man is eating”? Or, do you care that “They are cooking pasta”?

COMPELLING YET INCOMPREHENSIBLE INPUT

There are plenty of examples of content which fall into this category.

One situation which springs to mind is when immigrants are immersed in their target language. Indeed, they find that they are constantly surrounded by the language they’re trying to acquire. For example, advertising billboards, the radio and people talking on the street. Nevertheless, these immigrants still fall short when it comes to picking up enough language to reach at least the intermediate level.

In reality, English people don’t communicate in a way that makes the language comprehensible enough for many immigrants.

Just recently, I wrote about the benefits of learning from authentic materials and resources.

One such resource is TV programs or series aimed at native speakers of a target language.

Language learners may be gripped by the storylines and realism of a TV series. Unfortunately, they might not understand much of the dialogue.

I remember when former Arsenal manager Unai Emery admitted that he watched gangster drama Peaky Blinders to help him learn English.

After a year and a half in London, Emery's listening and speaking skills were poor. Hence, the tricky West Midlands accent and colloquial language in Peaky Blinders evidently did little to help him perfect his English.

Frankly, I’m not sure whether he acquired any language at all from watching the show. I don't question, though, that it was compelling viewing for Emery.

Compelling and comprehensible input

In more advanced classes, I’m a big believer in teachers sharing personal stories to motivate and intrigue students.

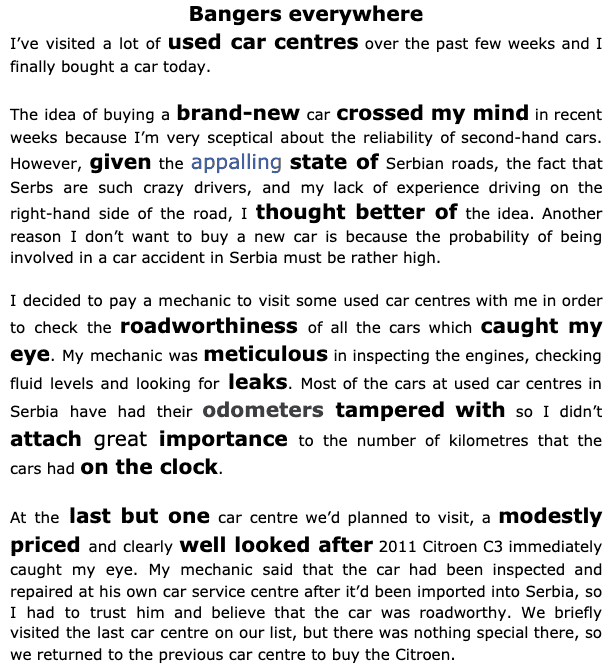

The text below is a true story of mine summarising my experience buying a secondhand car in Serbia:

The wonder of such self-written texts is that they bridge the gap between written English and spoken English. My aim has always been to try to replicate spoken English when writing such texts. It’s no easy task, but feedback from students down the years has been overwhelmingly positive.

Hence, in my view, one of the best comprehensible input strategies and leading ways to create compelling comprehensible input is to share true stories rich with challenging lexis and the following characteristics and benefits:

- The avoidance of formal English - Dialogues and sentences on many language learning apps I’ve seen contain excessively formal and polite language. However, native speakers of English rarely speak so formally

- Natural features of spoken English - To bring learners closer to natural spoken English, my texts contain contractions (I’ve, I’m), commonly used collocations and non-complex grammar structures

- Use of the first-person - I find that too many English language learning texts in coursebooks and on the Internet are too descriptive and “newsy”. By using the first person (“I”), learners are able to relate to my experiences and really come out of their shell (open up and speak) if they’ve been in similar situations to me

- Emphasis on connected speech - the phonological phenomenon of linking words together to create natural and smooth speech

- Emphasis on the schwa sound - The schwa sound gives English a unique sound and rhythm. Many short grammatical words, such as prepositions and pronouns, are reduced to a schwa sound. For example, the word “for” sounds more like /fə/ (fuh) in rapid speech. Hence, using schwa helps to speed up speech and create a perception of fluency

I believe that texts such as the one above embody comprehensible input for the average intermediate level learner. Some of the lexis in the text might be challenging for them. Nevertheless, there are more than enough structures and collocations which they should recognise.

I recommend teachers to voice record the texts and expose learners to audible input before launching into reading. After all, the emphasis should be on schwa, connected speech and how natural features of spoken English, such as contractions, tend to dominate a native speaker’s utterances.

READING AND BEING IN A STATE OF “FLOW”

Krashen correlates compelling reading input with being in a state of 'flow'.

The psychological concept of 'flow' (i.e. being 'in the zone') was recognised by Hungarian-American psychologist, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

Krashen recognises that, during reading, readers lose themselves in the book. Indeed, “our sense of time is altered and nothing but the activity itself seems to matter” (Krashen, 2011).

Short articles in coursebooks don’t cut the mustard when it comes to enchanting students. This is due to the mundane or bizarre themes coursebook writers tend to select.

So, what about the use of novels and books in the ELT classroom?

It would take a very savvy teacher to locate lengthy reading material, such as a novel, compelling enough to captivate an entire group of students.

Nothing is impossible. Here’s a list of books which might suit groups of higher level learners.

Finally, what about the argument that ELT teachers should allow each individual student to engage in some self-selected reading on a weekly basis?

COMPELLING COMPREHENSIBLE INPUT - Leading the way WHEN IT COMES TO COMPREHENSIBLE INPUT STRATEGIES

It would take a brave soul to argue against Krashen’s Compelling Input Hypothesis, and its place among the most elite of his comprehensible input strategies.

When it comes to private language schools and the typical ELT classroom, there would be issues with persuading teachers and academic managers to overlook the grammatical syllabus and coursebooks.

However, for higher level groups, at least, why can’t schools and ELT teachers reserve half an hour each week for their students’ self-selected reading?

Krashen came up with the hypotheses.

It’s down to us ELT teachers to step out of our comfort zones and hand over some autonomy to our students. .

References:

Krashen, S. (2011). The Compelling (not just interesting) Input Hypothesis. The English Connection: KOTESOL. 15 (3).

Krashen, S. (2013). Rosetta Stone: Does not provide compelling input, research reports at best suggestive, conflicting reports on users’ attitudes. International Journal of Foreign Language Education, vol. 8 (1)

https://beyondlanguagelearning.com/2019/04/26/abundant-compelling-comprehensible-input-what-were-aiming-for-and-how-to-get-there/