Why every language teacher should read The Lexical Approach by Michael Lewis (book review)

I started teaching in 2006, but I’ve been a ‘lexical’ teacher since 2010. Therefore, it might come as a surprise to you that it’s taken me nearly ten years to do what all ‘lexical’ teachers should do - read The Lexical Approach by Michael Lewis.

My evolving beliefs as an EFL teacher, and my own experiences as a language learner, led me to believe that linguistic competence cannot simply result from storing and memorising thousands of single-word units and doing pointless grammar exercises.

Indeed, as Lewis put it: “The grammar/vocabulary dichotomy is invalid; much language consists of multi-word ‘chunks’ “(vi).

Hence, I now give less long-winded grammatical explanations to students than I used to. I focus more on getting students to respect overall meaning rather than letting them get weighed down by their grammatical insecurities.

For instance, consider the multi-word chunk at the end of the day. Why bother to explain the use of the? Or the preposition at? Let’s just get students to focus on meaning.

RefLECTING ON WHAT HAD GONE BEFORE THE LEXICAL APPROACH

Lewis welcomed a shift away from grammar-based syllabuses towards the use of activities in the classroom which stimulated communication. He also craved for a greater emphasis on receptive skills. Unfortunately, the Communicative Approach (CA) didn’t quite herald the revolution that Lewis had anticipated back in the 1970s. In fact, Lewis argued that textbook writers and publishers hadn’t done enough to push through that “wind of change” when it came to implementing fresh methodological implications.

Frankly, who could disagree with Lewis? Coursebooks continued to be wrapped up in a structural syllabus. This was despite the fact that communicative tasks began to make their way into coursebooks after the Communicative Approach came to the fore. A structural syllabus embodies the notion that learners should master the tense system in a linear fashion. Traditionalists believe that the present simple can’t be covered until the verb be has been dealt with. After the present simple, mixed present simple and present continuous practice should ensue. This pathetic structural steam train rolls on and on.

In the early 1970s, the term ‘functions’ was introduced into language teaching. In essence, a function is the social purpose of an utterance (Lewis, 1993). For instance, the function of the question Would you like a cup of tea? is clearly to offer something. In the old days, structuralists might have broken down and analysed the question to death. Common sense eventually prevailed, and instructors began to introduce such sentences early in learning programmes, without structural analysis.

Lewis argued that many types of lexical phrases, whether serving a function or not, can be introduced in the early stages of learning - without scrutiny. He pointed out that speech can be processed more rapidly - both receptively and productively - if these chunks are treated as single, UNANALYSED WHOLES (p.90). Research at the time confirmed his belief.“LANGUAGE CONSISTS OF GRAMMATICALISED LEXIS, NOT LEXICALISED GRAMMAR”

This quote is very recognisable for teachers and linguists familiar with Lewis’s work.

Lewis alluded to quite a few ideas with this quote. First of all, he advocated an increased role for word grammar (collocation and cognates). Correspondingly, sentence grammar - the mastery of tenses and different sentence patterns - would assume a lesser role, at least until post-intermediate levels.

Lewis’s mission was to get students and teachers to stop equating vocabulary with single words. It’s a valid point. Many ‘bits’ of language (lexical items) are not made up of a single word: the day after tomorrow, I’ll see you tomorrow, by the way, coffee table.

There are various types of lexical items which can be distributed to lower level learners. These include:

- Short, hardly grammaticalised utterances - Just a minute; Not yet; Not at all; Certainly not.

- Sentence heads - Sorry to bother you, but can I just say that … ; That’s all very well, but …

- Polywords - These are phrases which behave like single words: by the way; look up to; put off; the day after tomorrow; taxi rank.

Lewis also made the point that language teachers tend to see vocabulary “in terms of nouns” (p.39). Moreover, the teaching of verbs “has largely been confined to work on their structure”. Looking back, I ripped off all those students who I pummelled with nouns, nouns and more nouns. Frankly, it’s convenient for teachers to drill words like door, window and bed. It doesn’t require much brain work.

Moving on to verbs, it’s easy to explain get and got in terms of their respective present and past aspects. What’s missing in ELT is teachers with a backbone; those who are willing to see words like get, have and take for their lexical value. Seriously, how many collocations, polywords and multi-word units contain the words get, have and take? Get up, get away with, have a meal, take the bus, take it to the limit … I could easily reel off another 2000 examples off the top of my head.

There are plenty of other words which deserve lexical treatment. Among them, as Lewis confirms, are modal auxiliaries, such as would (p.110). Ridiculously, would was treated as ‘the conditional’ in structural English language courses.

In my view, this shift away from structural analysis and tense-based teaching towards lexical teaching was more about treating students with dignity. I bet you one thing - most Callan Method teachers and structural syllabus teacher addicts didn’t learn a second language in the same manner that they presently teach. Most of them picked up languages through exposure, lots of mostly comprehensible listening (thanks, Krashen) and paying attention to lexical phrases.

MORE LEXICAL COURSEBOOKS PLEASE

Frankly speaking, I’ve always had the same feeling as Lewis : “coursebooks are commercial ventures … content and layout are chosen to maximise sales” (p.182). Coursebooks have also traditionally stuck by the grammatical syllabus to appease traditionalist teachers.

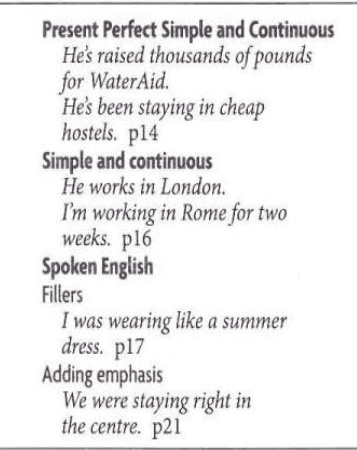

I haven’t analysed the most popular ELT coursebooks in any great depth to see the lexical state of play. However, let’s see how things stand in the Fourth Edition of New Headway Upper Intermediate:

How structurally predictable!

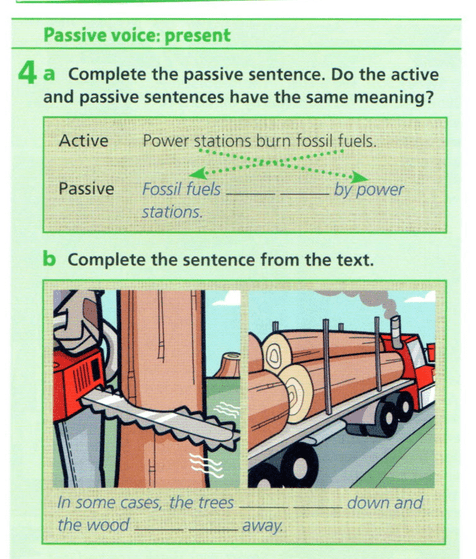

In the fourth edition of Project 4, here’s Tom Hutchinson’s attempt to get younger learners to get to grips with the passive voice. Unfortunately, we hardly use the passive voice in spoken English. Still, anything to fill the pages:

Frankly, we need more people like Hugh Dellar and Andrew Walkley to take ELT and its samey publishing merry-go-round by the scruff of the neck.

While analysing Dellar and Walkley’s Innovations elementary coursebook, it was clear that they had a mission to get away from focusing on the structure of verbs and so-called tense formation. There are plenty of examples in this coursebook of verbs appearing in their base form. To be clear on what that means, the base form is the version of the verb without any endings (such as -ing, -ed and -s). It might include the infinitive form, without the to, and the present simple form: I always drink a glass of water before I go to sleep every night. This is exactly what Lewis called for: “a large repertoire of verbs in their base … form with increased attention to the highly frequent present simple” (p.110).MORE LEXICAL MATERIALS PLEASE - I’M TRYING MY BEST MICHAEL

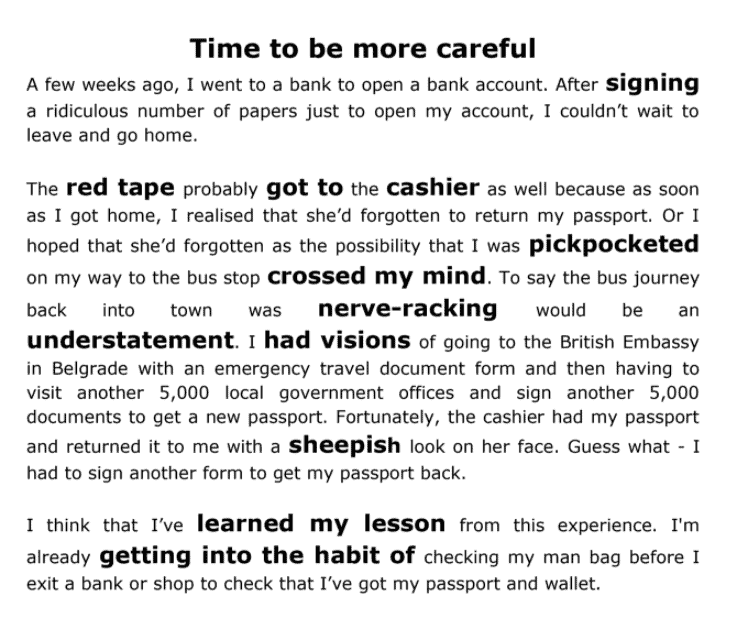

Over the years, I’ve written around 90 texts based on my own experiences living and working abroad, travelling and many other situations.

Certainly, I didn’t start writing these texts to become the centre of attention. I merely wanted my students to come out of their shell and share their own experiences based on my own. Secondly, I was determined to create materials with a highly lexical flavour. After some time, I began to use boldface to make key multi-word units and single words stand out. Of course, I encouraged my students to use as many of these phrases and words as they could in the discussion phase of the class.

For some mysterious reason, I’ve begun to wonder what esteemed ELT teacher educator, Scott Thornbury, would make of my texts. This is because he took a pop at Lewis for failing to specify how texts and discourses within a lexical approach would be selected and organised (Thornbury, 1998). Who I am to take on the ‘Special One’, but I think that Thornbury was barking up the wrong tree there.

When it comes to text distribution, what’s important is exposure, surprise and anticipation with what is to come. Then there should be revision, the revisiting of texts and the personalisation of new chunks. By personalisation, I mean encouraging students to write and voice record true sentences or stories about their lives using target chunks. Well, Scott, I do dish out my texts to my students oh-so haphazardly. It would be difficult to put them in order according to grammatical structures or a perceived level of difficulty.

Here’s one of my texts:

BROADEN YOUR HORIZONS - READ THE LEXICAL APPROACH BY MICHAEL LEWIS

Even for the most experienced and confident lexical teachers, I recommend they read The Lexical Approach by Michael Lewis for the occasional thought-provoking pearls of wisdom they’ll inevitably come across.

I have to admit that Lewis’s views on teacher talking time (TTT) caught my attention. I must be one of the least talkative teachers out there, partly due to my nature, and partly due to my evidently skewed views regarding student talking time (STT) and TTT.

Unfortunately, initiation courses, such as the CELTA, simplify the TTT/STT divide to the point of absurdity. More STT, less TTT - the CELTA trainers cry! I’m still a little stuck in my CELTA ways with regard to STT and TTT. It’s time to hit the books and English language journals because there must be a wealth of evidence out there supporting TTT. More importantly, the literature must offer some fascinating insights as to what high-quality TTT actually is. Presumably, productive TTT is not chatting to students about the weather.

Another area in which Lewis has got me thinking is error correction. I’m nowhere near as conservative as I used to be, and gone are the days of interrupting students in full spoken flow to correct them. However, I still pay too much attention to error correction, albeit usually at the end of a class.

Lewis offers some example sentences produced by native speakers, several of them in writing. One example is: “We sightsaw every morning, and then worked in the afternoons” (p.169). Most dictionaries probably do not list “sightsee” as a verb. To me - someone who’s always taught students the phrase “go sightseeing” - it sounds very awkward. Nevertheless. Lewis has a point: “Gifted speakers often bend and break the language into new meanings, creating according to need” (p.169). Lewis goes on: “Creative use, which communicates meaning, is clever and commendable, whenever meaning is successfully communicated. Looking for error … is a perverse way to look at language” (p.170).

Food for thought indeed.

CRITICISMS OF THE LEXICAL APPROACH

As with all other methods and approaches in ELT, the Lexical Approach has not been without its critics.

I’ve already mentioned Scott Thornbury’s stance towards the Lexical Approach. Michael Swan, another loveable figure in the world of ELT, also contradicted Lewis’s theories in his 2006 paper: Chunks in the classroom: Let’s not go overboard. Essentially, Swan argues that it’s all very well to arm learners with chunks, but it would be foolish of any teacher to believe that the grammar will magically fall into place. According to Swan: “a vast amount of exposure would be necessary for adult learners to derive all types of grammatical structure efficiently from lexis by the analysis of … chunks” (p.3).I’m not so sure that I can view interference errors “positively”. I’ve heard the same Polish-influenced errors almost every single day of my life for the last fifteen years. There seems to be no magical solution to the issue, apart from the personalisation of problematic structures. For instance, a Polish learner of English who keeps saying I very like instead of I like _____ very much, I like _____ a lot or I really like _____, should first of all create dozens of personalised sentences with the correct structure/s:

- My sister likes baked dumplings very much

- My son really likes playing chess

- I like my mum’s new boyfriend a lot

In essence, Lewis discounts a few grave issues when it comes to the overall proficiency of intermediate level learners. Sure, we need chunks and a Lexical Approach, but we can’t just dismiss issues like language interference. I suspect Lewis had never been in the trenches with a specific group of language learners for fifteen years. Hence, he wasn't able to feel what I feel now.

Finally, teacher trainer and materials developer, Leo Selivan, provides a list of articles that have been critical of the Lexical Approach over the years. Check them out.

Conclusion

If you read The Lexical Approach by Michael Lewis, you won’t come across much groundbreaking genius. Lewis just cleverly synthesised what had gone before into a neat package. Good old common sense logic. Take, for instance, his stance on the teaching of full forms versus contracted forms. We should get students to use contractions because they're a natural feature of native speaker speech.

Back to Hugh Dellar again. Dellar wrote a thoughtful memoriam to Lewis, stating that Lewis was “a great agitator, a disturber of norms, a challenger of assumptions.” When on stage, Lewis had a “razor-sharp wit” and “an inability to suffer fools gladly”.

I regret that I never saw Lewis in action. Judging by the tone of The Lexical Approach, I suspect he was a humourous character who knew how to stick up for himself.

References:

Lewis, M. 1993. The Lexical Approach: The State of ELT and a Way Forward, London: Commercial Colour Press

Swan, M. 2006. Chunks in the Classroom: Let's not go Overboard, The Teacher Trainer, 20/3

Thornbury, S. 1998. The Lexical Approach: A Journey Without Maps?, MET, Vol 7, No 4