Teaching English as a non-native speaker: How I, as a “native”, view the situation

Teaching English as a non-native speaker. As I'm an Englishman, you may be wondering - who am I to comment on such a situation?

Well, I’ve been in this game for fifteen years. When I worked in language schools in Poland and Bosnia, I was overcome with empathy and admiration for the local teachers. They worked longer hours than I did. Before I did my master’s and studied the English language, they were certainly better qualified to teach English than I was.

For me, it was never “us” versus “them”. I never felt I had one up on the local teachers because I “knew” English better than they did.

Getting into TEFL

Late August 2006.

TEFL.com threw up a vacancy at a language school in the southeastern Polish town of Dębica.

I realised that Dębica was hardly the thriving metropolis to sweep me off my feet and make me want to stay forever.

However, I needed to get my foot on the ladder and build my career as a TEFL teacher somewhere. Besides, Dębica wasn’t far from magic Kraków. I spent nearly every weekend there in the nine months I worked in Dębica.

Now, getting to the point. The job ad promised the “chosen” native speaker free accommodation, health insurance and a decent salary. No mention of a degree in linguistics or English Language Teaching - just a CELTA and any old bachelor’s degree would do.

I never stopped to think why this school had to explicitly state it was looking for a “native speaker”. What about non-native speakers of English who’d spent four years or more studying the finer nuances of the language? The qualified non-native speakers out there also knew more about language teaching methodology than I certainly did.

All in all, I was a native speaker of English. Employed to get bums on seats. Nothing more than a commodity with a lovely English accent. Frankly, I've never been too sure whether my Wellingborough accent is "lovely".

Thoughts and observations from my first year in TEFL

I must admit that I was thoroughly impressed with the attitude and professionalism shown by the non-native speaker teachers at my first school in Dębica.

Many of them were seasoned pros in the game with admirably high levels of English. When I listened to my colleagues speak, I wouldn’t say that they had native-like competence. However, as many of them taught kids and young teenagers, I guess that native-like competence was not an essential requirement. They were more than linguistically able and qualified to do the job.

I also deduced that teaching English as a non-native speaker is no walk in the park. Many of my colleagues worked all day in state primary and secondary schools. They would then come to the private language school after their regular jobs to teach. Who knows, maybe they had other private students in the evenings as well.

Perhaps I did feel a bit guilty.

The school looked after my English and colleague and me very well when it came to pay and accommodation. We didn't have to pay any rent to lodge where we did.

In 2006, I never stopped to consider the situation in any great depth. Looking back, however, something was wrong when an inexperienced and pedagogically inept English teacher from England could rock up in a small Polish town and be able to live much better than the highly-qualified non-native speakers.

Perhaps the (Polish) owner of this language school had simply got caught up in an ideology known as native speakerism.

What is Native Speakerism?

The main source of inspiration for this post was a 2021 thesis by Mr Tomasz Paciorkowski titled:

Native Speakerism: Discriminatory Employment Practices in Polish Language Schools

Paciorkowski, who has a PhD in linguistics, currently works as an assistant professor at the Kazimierz Wielki University in Bydgoszcz.

In his work, Paciorkowski examines a pervasive ideology in ELT known as native speakerism.

The term native speakerism was actually coined in 2005 by Adrian Holliday in his book The struggle to teach English as an international language.

To quote Holliday [2006]:

Native speakerism is a pervasive ideology within ELT, characterized by the belief that ‘native-speaker’ teachers represent a ‘Western culture’ from which spring the ideals both of the English language and of English language teaching methodology.

Negative assumptions that underpin the ideology include:

- Non-native speakers have little to contribute to the ELT profession and are therefore worse teachers than native speakers (the notion of cultural disbelief, put forward by Holliday (2015, in Paciorkowski, p.27)

- Learners of English learn the language to understand British and American culture

- The English language spoken by non-white and non-Caucasian populations, for example, in Kenya or India, does not enjoy the same status as British or American English

Research on native speakerism has mostly revolved around individual teachers’ actual experiences to document how they have been affected by the ideology. A case in point would be Lowe and Kiczkowiak’s 2016 paper which presented a duoethnographic study into the effects of native speakerism on the professional lives of two English language teachers, one “native”, and one “non-native speaker” of English.

Non-native speakers who have experienced discriminatory practices in language schools

In his 2018 PhD thesis, Native Speakerism in English Language Teaching: Voices From Poland, Marek Kiczkowiak - founder of TEFL Equity Advocates - wrote the following:

… the belief in inherent and unquestionable linguistic superiority of ‘native speakers’ is still very much the prevalent one both in the minds of SLA and ELT professionals, as well as the general public.

Hence, I will now turn my attention to this pervasive belief and the challenges that non-native speaker teachers face when it comes to the expectations of non-native students, supposed prejudice from native speaker colleagues and schools’ employment policies. The first story below illuminates the point that native speakerism may instil a worrying array of complexes in non-native speaker teachers.

The Curse of Native Speakerism

I recently came across a story about a Polish teacher of English in London called Kasia.

Essentially, Kasia had an evening FCE class two nights a week. Mr Hugh Dellar - the author of this story - had to cover the class for Kate on one particular occasion. So, Hugh went into class and introduced himself, before saying: “Right. So Kasia told me that you’re on page . . . “. Before Hugh could finish his sentence, however, one student interrupted with an abrupt “WHO?!”. “Kasia,'' Hugh replied. “Your teacher. Blonde hair. Younger than me. Smiley. Remember?” “You mean KATE?” another student exclaimed.

Hugh quickly twigged what was going on. Sensibly, Hugh decided it was best to go along with the baffled students: “Yeah, sorry. KATE, I mean. My bad.”

Anyway, Hugh called Kasia the next day to brief her on what had happened. Kasia, devastated that she’d been “found out”, revealed that she’d decided to anglicise her name as there were three Polish students in the group. Amazingly, Kasia had managed to pass herself off as a Brit for some considerable time.

Understandably, Kasia was frightened that these Polish students would complain if they found out they’d come to England, only to find themselves studying with a fellow Polish citizen.

Frankly, I am on Kasia’s side here. What was she to do? Who can blame her for putting her livelihood and career before the truth?

Hugh adopted a similar sympathetic stance in relation to Kasia’s situation:

Feelings of doubt and insecurity dog you; you feel that no matter what you do, you’ll never be good enough.

I wrote to Hugh to ask about the outcome of this story with Kasia. He responded promptly:

In the end, she came back, admitted she was indeed Polish, explained why she’d tried to hide this fact and made a clean breast of it all. Students responded far more positively than she’d expected them to, said they wouldn’t have known she wasn’t ‘native’ and she went on to become one of our best teachers in the EFL department there - always as Kasia, not Kate.

All in all, teaching English as a non-native speaker can’t be easy when inferiority complexes and the possibility of being “found out” hang over you.

A general overview of students’ attitudes towards non-native speaker teachers in Poland

In his blog post, The Curse of Native Speakerism (link in the previous section), Hugh Dellar points out that:

Social media is awash with adverts for courses that offer to ‘help you speak like a native’ … It’s no wonder that so many students claim to want ‘a native accent’ - without having any real awareness of the incredible diversity of accents that people who grow up speaking English as a first language actually possess.

Wise words from Hugh.

Many students of English have been duped into believing that their "accents” aren’t good enough. Hence, I believe that many struggling language learners challenge the credibility of non-native speaker teachers because they’re unable to get over their own inferiority complexes. Nobody likes to admit to their own vanity. So, it’s convenient for non-native students to shift the blame onto non-native speaker teachers.

Before I reveal a striking case of discrimination against a non-native speaker teacher by her students, let me dive into some of the research revealing the attitudes towards native and non-native teachers of English among Polish schoolchildren.

Paciorkowski (2021) refers to some work done by SLA researcher Vivian Cook. Cook (2000, cited in Paciorkowski, 2021) used a questionnaire to examine attitudes towards native and non-native teachers of English Polish schoolchildren. 45% of Polish school children declared that they’d prefer to learn with native speakers, while 25% would rather have a non-native speaker. The other 30% didn’t have an opinion on the matter.

Another Polish researcher who looked into the native speaker/non-native speaker dichotomy is Justyna Kula (2011). Kula conducted research on 91 high school students. Her findings didn’t necessarily paint a picture of doom and gloom. However, the participants’ responses and preferences are likely to have been influenced by all the usual stereotypes and presumptions:

In Kula’s study, the participants had mostly positive attitudes towards non-native teachers. One final statistic to support this observation is that 73% of the students admitted that whether their teachers are native speakers or not has little or no importance. Ultimately, the ability and competence of a teacher mattered more for the majority of the participants.

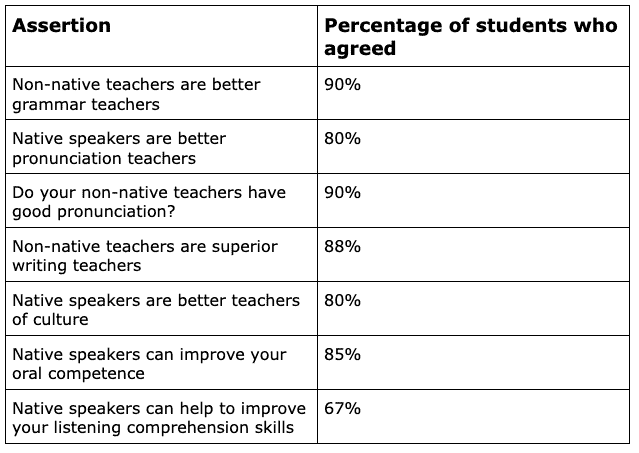

Now, let’s come to Kiczkowiak’s thesis (2018) once again.

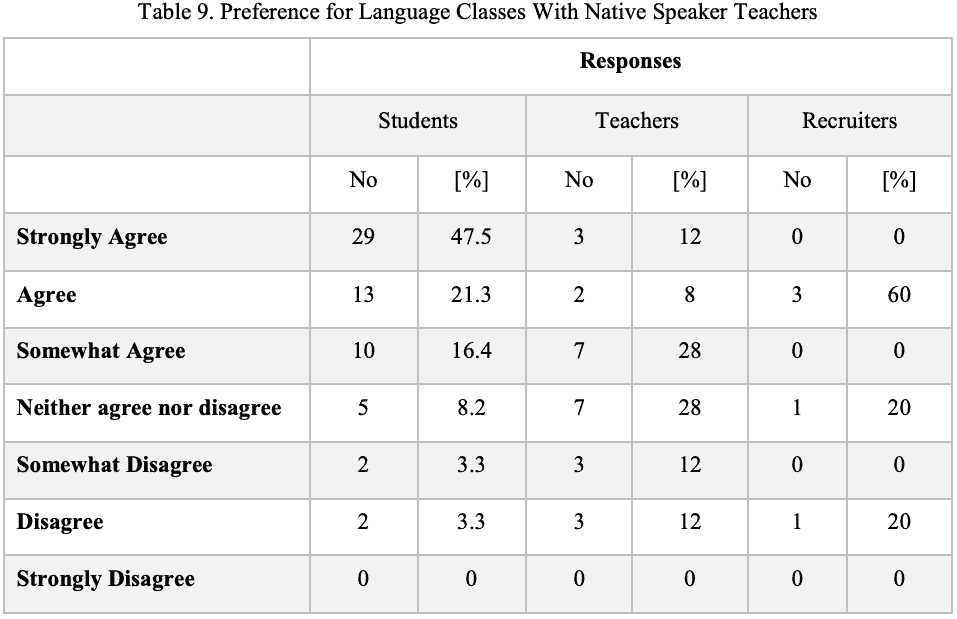

As the table below shows, the students Kiczkowiak surveyed had a strong preference for language classes with native speaker teachers (85%):

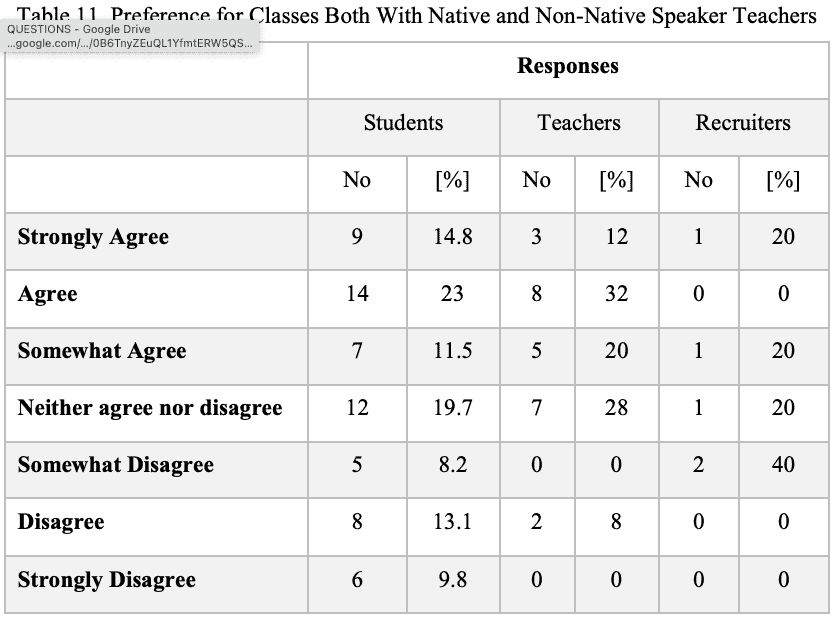

However, one chink of light for non-native teachers would be that 49% of participants preferred to have classes with both native and non-native speaker teachers:

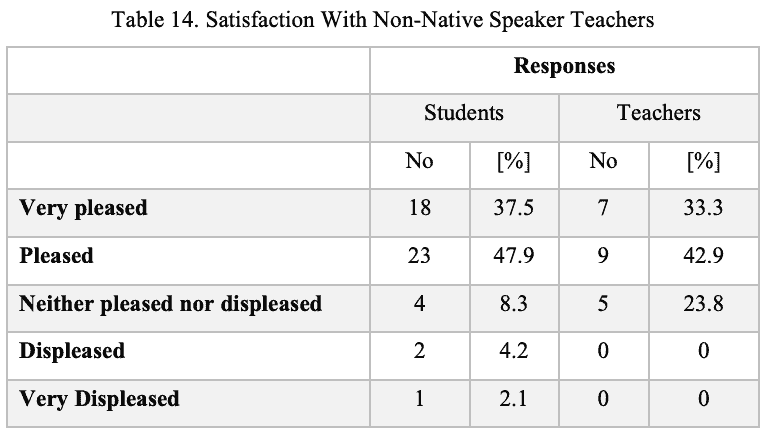

Finally, the vast majority of participants were satisfied with their non-native speaker teachers:

Overall, many language students lack awareness about what makes a “good” teacher. The automatic choice for most of them is to dismiss the wide-ranging qualities that non-native speaker teachers can bring to the table.

A true story of a non-native speaker teacher who felt discriminated against by students

Edited by George Braine, the book Non-Native Educators in English Language Teaching (2009) presents some compelling autobiographical narratives by non-native speaker teachers.

Let me now present one teacher’s story which is representative of how students undermine the credibility of non-native speaker teachers:

Jacinta Thomas, College of Lake County, Grayslake, Illinois, USA

This post has only really considered ELT, and the relationship between non-native speaker teachers and students whose first language isn’t English.

When it comes to Jacinta Thomas’s story - something a little different. Native speaker students.

After reading the first few lines of Jacinta’s narrative about preparing to teach a class of “native speakers of American English” on an academic program, I knew that things would quickly turn south for her, despite her being well-prepared for the class.

A few minutes after Jacinta entered the classroom, a young woman stuck her head in and stared at Jacina in confusion. The young woman then walked back outside to check the room number, came in again and asked: “Is this an English class?”

Immediately, Jacinta’s back was against the wall. Here’s what she wrote about the need to establish credibility (p.5):

We often find ourselves in situations where we have to establish our credibility as teachers of ESOL before we can proceed to be taken seriously as professionals. In the words of a colleague of mine, "I sometimes feel that I have to do twice as well to be accepted.

The other story I’d like to present concerns “one of the best writing classes” Jacinta has ever taught. The rapport between Jacinta and the students was very good. Jacinta felt right at ease with the group; they’d often spend time talking as a class or after class. However, on one occasion, a topic came up pertaining to race and language. One of Jacinta’s students (in Braine, p.8) said:

You know when I saw you enter the class on the first day, I was disappointed. I had spent a lot of money to come to the United States and I was hoping to get a NS to teach the class. When I first saw you, I felt certain that I wouldn't like your class.

Effects of Challenges to Credibility by Students

Thomas (in Braine, p.9) mentions that the “effects of these challenges to their credibility can sometimes be unnerving if not debilitating.”

Who could doubt her?

Moving on. There’s nothing worse than receiving a heap of praise and positive evaluations before coming across the inevitable dagger to the heart. Thomas (in Braine, p.10) wrote about some student evaluations she had read. Generally, the evaluations were positive. Students praised Thomas for her “encouragement”, “advice” and “good style to teach”.

Then, the killer blow:

What did you like about the course, the instructor and the instructional style?

"She was very kind, so I can learn English comfortably."

What did you dislike?

"We need native speaker teacher. It will be better."

Inevitably, Thomas’s heart sank. Frankly, I would have felt the same. Positive evaluations about your teaching abilities don’t mean anything when somebody’s criticised you for who you are.

It must be hard to keep picking yourself up again after disappointments like this.

As an Englishman, I really do feel for teachers like Jacinta Thomas.

Non-native speaker teachers who feel discriminated against by native speaker teachers

I’m sure that I could find plenty of accounts of non-native speaker teachers who have felt discriminated against by native speaker teachers.

All I can say is that I’ve encountered nothing but cordial, professional and respectful relations between native speakers and non-native speakers in the language schools and universities I’ve worked for since 2006. These institutions of educational excellence include The University of Southampton, UK, where I taught EAP for four consecutive summers (2011-2014).

It is my contention that the overwhelming majority of native speaker teachers have nothing but respect for non-native speaker teachers.

English language teaching job ads - As I remember the situation between 2006-2013 and the way things are now

I haven’t got any recorded evidence, but I clearly remember recruiters expressly looking to hire “native speakers” on tefl.com when I browsed job ads on tefl.com between 2006 and 2013.

In May 2002, the European Commission (EC) announced that:

The Commission is of the opinion that the phrase “native speaker” is not acceptable, under any circumstances, under Community law. […] the Commission recommends using a phrase such as “perfect or very good knowledge of a particular language” as a condition of access to posts for which a very high level of knowledge of that language is necessary.

Maybe most employers were just oblivious to EU law or they didn’t care about it.

These days, on tefl.com, the tone of job adverts is markedly different. Here are some replacement terms for "native speaker" I have found:

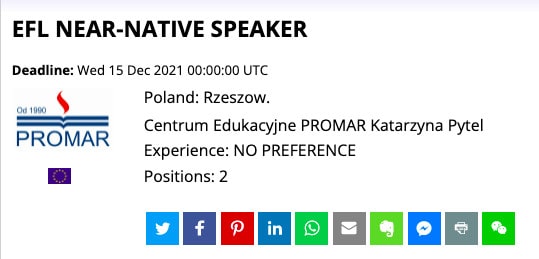

1. "Near-native speaker"

2. "Native level speakers of English"

3. “Both native and non native teachers”

I’d like to be optimistic. However, I just think that schools are using descriptions such as “native level speakers of English” to appease the EU. They know very well who they want to recruit.

Recruiters are merciless beasts. I found that out myself back in 2011 - and I am English. Essentially, I applied for around 40 UK-based jobs in September that year. Despite having a decent set of qualifications and a reasonable amount of experience, I didn’t receive one reply. Try telling me that my Polish surname (my grandfather was Polish) didn’t have any bearing on the wide berth those schools and institutions gave me.

Money chasing employers only care about paying customers who might “freak out” if they had a Kowalski, Czech or Brecel teaching them - even though they might be as English as your typical John Smith from Oxford. So, I would be wasting my breath trying to convince employers that I am not Polish. That I never, ever spoke Polish in the first eighteen years of my life. And that English people can have surnames that are not of Anglo-Saxon origin.

Dr Tomasz Paciorkowski on the topic of EFL job ads

I recently had the pleasure of chatting with Dr Tomasz Paciorkowski on the subject of teaching English as a non-native speaker and discriminatory job adverts. Here's what he had to say on the topic of job ads directed at native speakers:

Recently, I've seen many "native" and "non-native" teachers online having a knee-jerk reaction to any job ad directed at native speaker teachers only. Alas, not so much in Poland still, but I hope it'll change soon. I should also add that my hope has its basis in the fact that I've seen an increase in the number of teachers on, for example the largest Facebook group created by and for Polish teachers of English - Nauczyciele Angielskiego - tackling and discussing the issue of perceived "native speaker" superiority. It always makes my day.

Anyway, this is off-topic. Coming back to your question, unfortunately, I'm convinced that as long as potential clients continue believing that "native speaker" teachers are superior, private language schools will continue trying to navigate the market by appeasing teachers by introducing different naming conventions (i.e., native-level competence and pronunciation ONLY) while simultaneously exercising their discriminatory employment practices. It doesn't require language school owners to even try too hard as the criterion of: "native-level competence and pronunciation" is so open to interpretation that any decent "native" and "non-native" teacher can either meet it or not, depending on your recruiter's mood. Additionally, let's not forget the number of extralinguistic factors that are always at play here, for example, names and surnames considered "white" or not, countries of origin, etc.

Teaching English as a non-native speaker - Resilience is the key

Kiczkowiak (blog post no longer available) makes the point that we ELT teachers need to start talking about what “actually matters”. Not which language you picked up as a child, nor where you were born. At the heart of the matter is PROFESSIONALISM.

English and American people require pedagogical preparation to teach English.

Looking back on my first year as an ELT teacher, I was completely out of my depth. Frankly, I was a “coursebook page turner” who couldn’t get a tune out of my students. The CELTA course didn’t prepare me to teach English. Feel free to read about some of my earliest experiences and beliefs as an ELT teacher.

So, Marek Kiczkowiak, I totally agree with you:

the incessant comparisons between the two groups only distract us from the importance of professionalism.

I am sure that teaching English as a non-native speaker can be an extremely rewarding career.

Over to the employers, publishers, textbook writers, native speakers and students to stop discriminating against all those very professional and conscientious non-native English speaker teachers.

References:

Braine, G. 1999. “Voices from the Periphery: Non-Native Teachers and the Issues of Credibility”, in: Non-native educators in English language teaching. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 5-12.

Holliday, A. R. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford: Oxford University

Holliday, A.R. 2006. “Native-speakerism”, ELT Journal 60, 4: 385-387.

Kiczkowiak, M. 2018. 'Native Speakerism in English language teaching: Voices from Poland', PhD thesis, University of York

Kula, J. 2011. 'The Polish secondary school students’ attitude towards native and nonnative speaker teachers: A case study'. [Unpublished MA thesis, Jagiellonian University,Kraków].

Lowe, R.J. and Kiczkowiak, M. 2016. “Native-speakerism and the complexity of personal experience: A duoethnographic study”, Cogent Education, 3, 1264171.

Paciorkowski, T. 2021. 'Native Speakerism: Discriminatory Employment Practices in Polish Language Schools', PhD thesis, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań